SECOND QUARTERLY REPORT

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| STATUS OF

EMPLOYMENT AT RELOCATION CENTERS September 30, 1942 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name of Center | Number of Evacuees in Residence* | Number of Employed at Center | Number Residing Outside Center on Seasonal Farm Work |

| Manzanar | 9,056 | 4,159 | 1,060 |

| Colorado River | 17,245 | 7,711 | 561 |

| Tule Lake | 14,646 | 6,000 | 822 |

| Gila River | 11,553 | 3,900 | --- |

| Minidoka | 8,042 | 3,033 | 1,444 |

| Heart Mountain | 9,995 | 3,858 | 877 |

| Granada | 6,892 | 1,200 | 527 |

| Central Utah | 5,803 | 2,334 | 11 |

| Rohwer | 2,264 | 815 | --- |

| TOTALS | 85,946 | 33,010 | 5,302 |

| * Not including those away from the centers as members of agricultural work groups. | |||

Employment Outside the Centers

As the manpower shortage in western agriculture grew constantly more acute, opportunities for private employment of evacuees outside relocation centers increased steadily throughout the summer months. At the beginning of the quarter, there were approximately 1,500 evacuees from both assembly and relocation centers at work in the sugar-beet fields and other agricultural areas of eastern Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and Utah. As the summer wore on and the harvest season approached, new demands arose for evacuee labor not only in these four States but also in Colorado, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Arizona. In late August and throughout September, recruitment was speeded up at all operating centers. By the close of the period, 5,302 evacuees had left the relocation centers for group agricultural work and another several hundred originally recruited from assembly centers were still at work on farms in the intermountain region.

During the late spring and early summer, recruitment of evacuees for seasonal farm work was handled at both assembly and relocation centers mainly by representatives of the beet-sugar companies in collaboration with the United States Employment Service. Recruitment for the fall harvest season, however, was carried forward chiefly by the War Relocation Authority. Under a procedure announced by the Authority on September 1 and actually initiated some weeks earlier, each farm operator in need of evacuee workers was required to fill out an "Offer of Employment" form indicating definitely the type of work involved, its probable duration, the wages offered, and the housing facilities available. These forms were submitted by the farm operators to the nearest office of the Employment Service and then forwarded to relocation centers for submission to the evacuees. Prime advantage of the procedure was that it gave the individual evacuee a somewhat clearer picture of the conditions under which he might work and thus tended to accelerate the whole recruitment process.

Meanwhile employment opportunities began developing for evacuees in a variety of non-agricultural lines in many parts of the country. In September one group of twenty former railroad workers were permitted to return to their former occupations as maintenance workers on a railroad in eastern Oregon. During the same month two transcontinental railroads filed applications with the Authority for more than a thousand maintenance employees. Before the close of the quarter, the Authority had received requests for office workers in Chicago, social case workers in New York, seamen for Atlantic shipping, hotel workers in Salt Lake City, settlement house workers in Chicago, science teachers in North Dakota, an architect in Philadelphia, jiujitsu instructors at an eastern university, wine chemists in Oregon, linotype operators in Utah, diesel engineers in the Midwest, dental technicians in Cleveland, laboratory technicians in a hospital in Michigan, and many others.

Leave Regulations

As the Nation's manpower shortage grew steadily more

widespread and acute throughout the summer months, increasing emphasis

was placed by the War Relocation Authority on evacuee employment

outside the relocation centers. With every passing week, it became more

and more obvious that the productive energies of some 40,000 adult

and

able-bodied evacuees could not be used to maximum advantage

within

the

boundaries of these government-operated communities. Accordingly, a

program under which properly qualified evacuees might leave the centers

indefinitely for private employment, higher education, and other

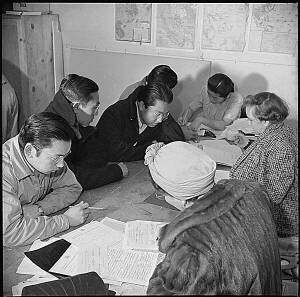

purposes was gradually developed throughout the second quarter. [PHOTO:

Residents of Japanese ancestry registering for indefinite leave in

Block 10. (Manzanar, 02/11/1943)]

productive energies of some 40,000 adult

and

able-bodied evacuees could not be used to maximum advantage

within

the

boundaries of these government-operated communities. Accordingly, a

program under which properly qualified evacuees might leave the centers

indefinitely for private employment, higher education, and other

purposes was gradually developed throughout the second quarter. [PHOTO:

Residents of Japanese ancestry registering for indefinite leave in

Block 10. (Manzanar, 02/11/1943)]

The first evacuees to leave the centers for group

agricultural work in the sugar-beet fields were released under a series

of civilian restrictive orders issued by the Western Defense Command.

Each of these orders was issued only to cover one or more specific

counties and only after the Governor of the state and county officials

had given assurances that law and order would be maintained. In each

case, the evacuee workers were required to stay at all times within

the

county or counties covered by the order and to return to the center at

the termination of the job. In short, the procedure was designed

merely

to cover seasonal agricultural work; the problem of leaves for

year-round employment and for higher education still remained.

The first step toward adoption of this problem was taken on July 20 when the Authority adopted a tentative policy permitting indefinite leaves. Under this policy, only American-born evacuees who had never lived or studied in Japan were permitted to apply for indefinite leave; and such leaves were granted only to applicants who had definite offers of employment somewhere outside the eight western States (i.e. the seven westernmost States plus Montana) which are included in the Western Defense Command. Before an indefinite leave permit was granted by the National Director in any individual case, the applicant was carefully investigated by the WRA staff at the center and a record check was made with the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Just before the close of the quarter, on September 26, the Authority issued a considerably more comprehensive and liberal set of leave regulations which appeared in the Federal Register of September 29 and were to become effective on October 1. Under these regulations, any evacuee -- citizen or alien -- may apply for leave to visit or reside in any locality outside the evacuated area. Three types of leave from relocation centers are covered by the regulations: (1) short-term; (2) work-group; and (3) indefinite.

Short-term leave is intended for the evacuee who wishes to leave the center for a period of a few weeks or so in order to consult a medical specialist, negotiate a property arrangement, or transact some other similar personal business. It is granted by the Project Director (the WRA official in charge of the relocation center) for a definite period after careful investigation by the WRA staff at the center. In cases where the Project Director denies an application for short-term leave, appeal may be made to the National Director whose decision is final.

Work-group leave is designed for evacuees who wish to leave the center as a group for seasonal agricultural work. Like short-term leave, it is granted by the Project Director for a definite period (which may be extended) and is subject to investigation at the center. Wherever possible, a record check is made with the FBI and the intelligence services on applicants for work-group leave. But such leave my be granted by the Project Director without this check if he feels that circumstances warrant.

Indefinite leave is granted to evacuees only by the National Director and only if four specific requirements are met: (1) the applicant for such leave must have a definite offer of a job or some other means of support; (2) he must agree to keep the WRA informed of any changes of job or changes of address; (3) his record at the relocation center and with the FBI and the intelligence services must contain no evidence of disloyalty to the United States; and (4) there must be reasonable evidence that his presence will be acceptable in the community where he proposes to make his new home.

All these types of leaves may be granted subject to such specific conditions as circumstances seem to warrant and may be revoked by the National Director in any case where the war effort or the public peace and security seem to be endangered.

With the adoption of the leave regulations, the movement of the Japanese-American people who formerly lived on the far western frontier entered its fourth, and perhaps its final phase. The first phase was the period of voluntary evacuation which occurred during late February and most of March when some 8,000 people of Japanese ancestry left the Pacific Coast military zones on their own initiative and resettled in the interior States. The second phase was the planned, orderly, supervised movement to assembly centers which took place between late March and early June. The third phase was the transfer to relocation centers which has already been described in this report and which was nearing completion as the second quarterly period closed on September 30. The fourth phase, made possible by leave regulations, might be called the period of resettlement outside relocation centers.

As the quarter closed, the Authority was making definite plans for this phase of the program and placing special emphasis on it. In fact, resettlement outside relocation centers had become the primary aim of the relocation program. This does not mean that the Authority was contemplating an immediate and wholesale exodus from the centers. The somewhat elaborate machinery of checks and clearances involved in applications for indefinite leave, the difficulties encountered by evacuees in arranging for jobs without the opportunity to deal with prospective employers in person, the still-evident anxieties felt by many communities towards all people of Japanese ancestry, the reluctance of many evacuees themselves to leave the sanctuary of relocation centers in time of war -- all these things suggested that individual resettlement would doubtless be a slow and gradual process. Within the limits prescribed by national security and administrative expediency, however, the Authority had determined to work toward a steady depopulation of the relocation centers and a widespread dispersal of evacuees throughout the interior sections of the country. This, in essence, is the real meaning of the leave regulations which became effective on October 1.

Student Relocation

Looking forward to the opening of the fall term at colleges and universities, the War Relocation Authority and the non-governmental National Student Relocation Council intensified their efforts throughout the summer to arrange for the attendance of properly qualified evacuee students at institutions outside the evacuated area. By September 30, a total of 143 colleges, universities, and junior colleges had been approved for student relocation by both the War and Navy Departments. Included were such liberal arts colleges as Swarthmore, such state universities as Nebraska and Texas, such women's colleges as Smith and Radcliffe, such Catholic institutions as Gonzaga, such teachers' colleges as Colorado State College of Education, such theological seminaries as Union, such technical institutions as the Milwaukie College of Engineering, and such specialized schools as the Northern College of Optometry and the Oberlin Conservatory of Music.

Under the tentative leave policy adopted on July 20, a total of 250 students were granted educational leaves from assembly and relocation centers prior to September 30. Some of these students left during late July and August to attend summer sessions at various institutions, but the majority went on leave in September and resumed their educations with the opening of the fall academic term. A number of additional applications for educational leave were pending as the quarter ended.

Conservation of Evacuee Property

During the quarter, the responsibility for assisting evacuees in conservation of their property -- a responsibility which was handled by the Treasury Department, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, and the Farm Security Administration at the time of evacuation -- was finally assumed by the War Relocation Authority. To carry this work forward, a Division of Evacuee Property was established in the San Francisco office and small branch offices were set up in Los Angeles and Seattle. The Division made its services available to evacuees in connection with all property problems which arose subsequent to evacuation or all such problems which the evacuee could not handle himself or through an authorized agent.

The following list indicates the principal services which the Division of Evacuee Property was established to render for evacuees:

1. Secure tenants or operators for both agricultural and commercial properties.2. Negotiate new leases or renewals of existing leases.

3. Obtain buyers for real or personal property of all kinds.

4. Effect settlement of claims for or against an evacuee.

5. Adjust differences arising out of inequitable, hastily made or indefinite agreements.

6. Obtain an accounting for amounts due, and facilitate collection thereof.

7. Ascertain whether property is being satisfactorily maintained or whether damage or waste is occurring.

8. Check inventories of goods and equipment, and recommend utilization of material for the best interests of the evacuee and the nation.

The Division works toward two main objectives: (1) conservation of property in behalf of the evacuee and (2) promotion of the use of that property in behalf of the national war effort. Usually these two objectives are intimately related. Farmlands, for instance, need to be kept in production to provide the food so much needed by America's armed forces at home and abroad and in discharging our obligations under the Land-Lease program to our allies. Finding a competent tenant for an evacuee's farm, if the evacuee has been unable to do so, is thus a service both to the evacuee and to the nation at large. In much the same way, the finding of competent operators for residential properties -- apartment buildings, hotels, and homes -- in a city where war industries have created an acute housing shortage is a service in behalf of the owner, the community, and the national war program.

Around Los Angeles, most of the requests for property assistance received by the Authority involved the liquidation of small shops or the disposal of store furnishings and fixtures. In all such cases, bids were obtained and submitted to the owners. In the Seattle area, on the other hand, the problems were largely agricultural and presented serious difficulties because of the labor shortage that has interfered with harvesting the berry and fruit crops. In Seattle, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, there were many commercial property problems including the operations of hotels and rooming houses.

During the quarter, conferences were held with the Farm Security Administration, with officials of the Federal Reserve Bank in San Francisco, and with the Federal Reserve Branches in Seattle, Portland, and Los Angeles. Information gathered by both agencies on evacuee properties was made available to the Authority. Conferences were also held with San Francisco representatives of the Alien Property Custodian to clarify the understanding of each office as to the functions and activities of the other and to eliminate duplication and conflict.

Household goods and other personal properties which evacuees could not readily take with them to assembly and relocation centers presented a wholly different set of problems. At the time of evacuation, the Federal Reserve Bank at San Francisco and its branches on the West Coast acting for the War Department leased 19 warehouses (totaling 386,000 square feet of space) in the principal cities of the evacuated area and offered to store the household furnishings and similar properties of evacuee families without charge until such times as these goods could be shipped to relocation centers. Only 2,867 families, however, took advantage of this service. Hundreds of other families stored their furnishings in community churches, stores, private warehouses, and other buildings in widely scattered communities.

During the quarter, responsibility for the storage of evacuee personal property was transferred to the Authority by Federal Reserve and leases for all 19 warehouses were assigned to the Evacuee Property Division. By September 30, seven of these warehouses with a total of 84,000 square feet of space had been cleared, either by shipments to relocation centers or by transfer to other warehouses not completely filled. Meanwhile, the Authority agreed to provide storage for evacuee personal properties stored in private buildings if the evacuee owner would first pay the cost of transportation to a government-leased warehouse where WRA could assume charge. At the close of the period, the Evacuee Property Division was making plans to reopen several of the cleared government warehouses in order to receive the property formerly stored by evacuees in private buildings.

Evacuee Self-Government

Under a tentative policy formulated by the War Relocation Authority in early June, evacuee residents at all operating relocation centers took steps to establish temporary community governments during the summer months. On August 24, the Authority adopted a more definite policy on this question and encouraged the evacuees to move toward a more stable form of government at the earliest feasible date. By the end of September, temporary community councils had been elected at all centers except the two in Arkansas. At the three oldest centers -- Manzanar, Colorado River, and Tule Lake -- the evacuees were already drawing up detailed plans for a long-range governmental structure.

Under the policy adopted on August 24, community government at the relocation centers will assume a form roughly comparable to municipal governments throughout the United States. Five main type of governmental bodies were suggested by the Authority to meet the needs of the centers.

1. The temporary community council is designed to serve as an interim point of contact between the WRA staff and the evacuee residents during the period when the community is getting settled and while evacuees are still arriving. Its function is to advise with and make recommendations to the Project Director pending establishment of a long-range governmental system. All residents 18 years or over are eligible to vote in the election for members of the temporary council. The general rule, however, is that members of the temporary council must be American citizens 21 years or over.2. The organization commission is comparable to a constitutional convention. Selected by a variety of methods and generally including some of the more experienced alien residents as well as the younger American citizens, the commission is set up to draft a long-range plan of government for the center. The plan finally developed is first submitted to the Project Director (who makes certain that it is consistent with WRA policy) and then is laid before the whole community in a special referendum. If approved by the Project Director and by a majority of the qualified voters, it becomes, in effect, the official charter for the community government and can be amended only by a majority of the qualified voters. By the close of the quarter, such commissions had been selected and were conducting their deliberations at Manzanar, Colorado River, and Tule Lake.

3. The community council is the legislative and policy-forming body of the long-range governmental set-up. Under the policy of August 24, both the basis of representation and the method of selection of the council were left open for decision by the organization commission. In order to recognize the special status of American-citizen evacuees, the Authority decided to limit membership on the councils to citizen evacuees 21 years of age or over. All residents 18 years or over, however, are entitled to vote, to hold non-elective offices in the community, and to serve on committees of the community council.

At some of the centers, special advisory committees composed of alien residents will probably be formed to consult with the council on questions of community policy especially those affecting the alien group. The principal functions of the council are (a) to enact regulations in the interest of community welfare and security and prescribe penalties (but not fines) for their violation; (b) to present resolutions to the Project Director; (c) to solicit, receive, and administer funds and property for community purposes; and (d) to license and require reasonable license fees from evacuee-operated enterprises. The policy-forming functions of the council are, of course, in addition to and not in any sense a substitute for those exercised by the Project Director and the WRA administrative staff.

4. The judicial commission, composed ordinarily of three to nine evacuee members, will be analogous to a criminal court in an ordinary American community. It will try evacuees who are arrested for alleged violation of community statutes and will hand down decisions which will be promptly submitted to the Project Director for review. Decisions which are not overruled by the Project Director within 24 hours after submission will become final. From a strictly legal standpoint, the judicial commissions at relocation centers will not have any status as courts. Although they will perform court-like functions, they will actually be administrative bodies making recommendations to the Project Director.

5. The arbitration commission is the relocation community counterpart of a civil court under American law. Its function is to hear any dispute of a civil nature between residents and to recommend a method of settlement to the Project Director. Composition of this commission and method of selecting its members are to be decided at each center by the organization commission and made a part of the community charter.

The position of block manager, which was established by the close of the quarter at nearly all operating centers, is quite distinct from the community council. In contrast to the council members, block managers are evacuee administrative officers, appointed generally by the Project Director, to serve as his personal liaison with the residents of the various blocks in the community.

They may be young American citizens but are more likely to be men of considerable maturity and therefore from the alien group. Among other duties, a typical block manager will (1) keep the residents of his block informed of official rules and policies announced by the Project Director; (2) see to it that the physical plant is kept in a state of repair; (3) collect and distribute mail; (4) assist in the adjustment of housing difficulties; (5) distribute supplies such as brooms, soap, and blankets; and (6) assist residents in emergency cases such as serious illness.

Consumer Enterprises

Under a policy adopted on August 25, evacuees at all

relocation centers were definitely encouraged to set up consumer

enterprises (such as stores,

canteens, and barber shops) and to

establish at each center an over-all consumer cooperative association

organized along consumer cooperative lines. These associations, once

organized and incorporated, will take over management of all stores and

service enterprises previously established by the Authority and will

assume full responsibility for setting up and managing any similar

undertakings needed in the future. By the end of the period,

considerable progress in the organization of such associations had been

made at all the older centers. But only one center -- Manzanar

-- had a

fully organized association actually incorporated under state law.

[PHOTO: "Typical scene in the Community Enterprise Stores at the Heart

Mountain Relocation Center. Chief stocked items are tobacco, drug

sundries, a limited

consumer cooperative association

organized along consumer cooperative lines. These associations, once

organized and incorporated, will take over management of all stores and

service enterprises previously established by the Authority and will

assume full responsibility for setting up and managing any similar

undertakings needed in the future. By the end of the period,

considerable progress in the organization of such associations had been

made at all the older centers. But only one center -- Manzanar

-- had a

fully organized association actually incorporated under state law.

[PHOTO: "Typical scene in the Community Enterprise Stores at the Heart

Mountain Relocation Center. Chief stocked items are tobacco, drug

sundries, a limited

supply of canned and packaged groceries and general notions. Stores are

operated on a cooperative basis. The limited profit is returned to the

evacuee residents." (09/16/1942)]

At most centers, stores or canteens of one kind of another were established within a few days after arrival of the first evacuee contingent. Initial stocks of goods were purchased on credit usually from nearby wholesalers or occasionally from large retailers who offered a discount. From a range of only a few items, often quickly sold, these stocks increased rapidly as the population swelled and new demands became known.

Under the policy of August 25, the final organizational pattern of the consumer enterprise association at each center was left largely in the hands of the evacuees. Three basic principles, however, were established: (1) unlimited voluntary membership for all residents; (2) only one vote per member and no proxy voting; and (3) limited interest rates plus restricted capital investment. All enterprises were encouraged to make sales at prevailing market prices and to distribute earnings in the form of patronage dividends rather than in the form of price reductions. Exceptions to this principle, however, were expected especially in the case of service-type enterprises such as barber shops and beauty parlors. Privately-owned consumer enterprises at relocation centers were expressly prohibited and business of the enterprises was strictly limited to a cash basis.

Education

Despite a complete lack of construction materials for school buildings, a marked shortage of qualified teachers, and a scarcity of school furniture and equipment, schools for evacuee children were either open or virtually on the point of opening at all centers (except the two in Arkansas) as the quarter ended.

At Manzanar the elementary schools opened on September 15 in unpartitioned recreational barracks without any lining on the walls or heat of any kind. Within two days a cold wave combined with dust storms at the center had forced the schools out of operation until the barracks could be lined and stoves could be installed. A reopening in early October was expected.

At Tule Lake both the elementary and high schools opened on September 14 with a total enrollment of more than 4,000 and classes were going forward as the quarter ended. At Heart Mountain on the final day of the period, one of the community's five elementary schools was opened and the others were getting ready for immediate operation. At most other centers, an opening in early or middle October was in prospect.

The most serious problem at all centers was the lack of construction materials. As indicated earlier, the Authority was trying to obtain priorities for such materials from the War Production Board when the quarter ended. During the period, however, not even a start was possible on school buildings at any of the centers, and there seemed little prospect that buildings would be completed and ready for occupancy anywhere before the beginning of the second school semester. At all centers barrack buildings intended for other purposes were being converted into temporary schoolrooms by laying linoleum on the floors and providing additional wall insulation.

The problem of textbooks and equipment was somewhat less acute. Although laboratory and shop-course facilities were virtually unobtainable, considerable equipment of other kinds was obtained from surplus NYA and WRA stocks and shipped to the centers. At the two California centers -- Manzanar and Tule Lake -- plans made during the first quarter to obtain free textbooks by having the schools incorporated as special districts in the regular public school system of the State were frustrated through an adverse ruling by the State Attorney General. Thousands of used text books, however, were obtained from schools in California, such as those in Los Angeles, which formerly had rather heavy enrollments of Japanese-American children.

As the quarter closed, most high school teaching positions had been filled at the older centers, but there was still a definite need for more elementary teachers at these centers and for instructors at all levels in some of the newer relocation communities. Properly qualified teachers of science and mathematics proved especially difficult to find. At most centers, it was necessary to recruit some teachers who had been out of the profession for a number of years; and at all centers, training courses for evacuee teachers were either under way or definitely in prospect.

Day nurseries for the children of pre-school age were opened at all centers except the very newest ones during the summer months. The opening of these nurseries enabled many of the younger mothers to accept jobs and replace men who had left the centers on sugar-beet employment. Teachers were recruited from the evacuee population and many had acquired a high degree of proficiency before the summer had ended.

Adult education classes were started at practically

all operating centers during the summer and additional courses were

being planned as the period ended. Some of the most popular courses

were in sewing, costume design, dressmaking, current events,

stenography, mathematics, and English.

Sewing School. Evacuee students are taught here not only

to design but make clothing as well. (Poston, 01/04/1943)

College extension courses were in prospect at most centers when the quarter ended. Although 250 evacuee students had transferred by September 30 to institutions outside the evacuated area under the student relocation program and many more were awaiting transfer at a later date, there were still hundreds who were unable, principally because of inadequate funds, to continue their education outside the centers. With these evacuees especially in mind, the Authority attempted during the quarter to arrange with State universities for courses to be given at the centers in the basic college subjects either by correspondence or through extension lecturers. No such courses, however, were actually initiated during the period.

Health and Sanitation

Considering the handicaps, the health record at relocation centers continued to be good throughout the second quarter. Especially at the older centers, definite improvements were made in community sanitation and in the hospital and clinical facilities for handling both in-patients and out-patients. Although housing and sanitary facilities were little above the standards established by the Geneva Convention, no serious epidemics occurred and the incidence of illness was no higher than would be expected in ordinary communities of similar size and age composition.

By September 30, the main hospital buildings constructed under supervision of the Army Engineers had been completed at Manzanar, Colorado River, Tule Lake, and Heart Mountain and were under construction at the other six centers. Additional buildings to handle out-patients were also under construction at Tule Lake and under consideration at Manzanar and Colorado River.

While shortages of some drugs and supplies were encountered, all those essential to the health of the evacuee patients were available. In some cases requiring special facilities which were not available, patients were transferred to hospitals outside the centers for suitable medical attention.

Lack of personnel was also a severe handicap. The number of available evacuee doctors and nurses, never completely adequate for the needs of the population, had to be stretched even farther during the summer months as evacuees moved from assembly to relocation centers. As this movement went forward, it was necessary to maintain a reasonably adequate health staff not only at the assembly centers being evacuated, but also at relocation centers being established, and on the trains carrying evacuees. Assignment of doctors and nurses was made primarily with a view to establishing a well-rounded medical staff at each of the relocation centers but also with an eye to the personal wishes of the individuals involved. In some cases, it was necessary in the interest of adequate medical service to assign evacuee doctors and nurses to a particular center without regard for personal preferences.

Essentially, the health program at most centers was still on an emergency basis as the quarter ended. Tentative plans, however, were being formulated at all but the very newest centers for a long-range program involving all aspects of community health service.

Community Welfare

Although subsistence is provided without charge to all evacuee residents of relocation centers and work is made available as rapidly as possible, there are inevitably a considerable number of people left without adequate means to provide for all their minimum needs. With such people especially in mind, the Authority during the second quarter established schedules and regulations covering both unemployment and public assistance grants.

Under the employment and compensation policy of September 1, provision was made for unemployment compensation. Any evacuee who applies for work and is assigned to a job or who is laid off through no fault of his own may apply to the Authority for such compensation covering himself and his dependents. Rates of unemployment compensation were established at $4.75 per month for men 18 or over; $4.25 for women 18 and over; $2.50 for dependent children between 13 and 17 inclusive; and $1.50 for dependent children under 13.

Under a policy adopted just one week earlier, the Authority

provided for public assistance grants to deserving evacuees who

are not

in a position to benefit either from the employment program or from

unemployment compensation. These would include (1) evacuees who are

unable to work because  of

illness or incapacity; (2) dependents of

physically incapacitated evacuees; (3) orphans and other children under

18 without means of support; and (4) the heads of families which have a

total income from all sources inadequate to meet their needs. [PHOTO:

"Evacuee orphans from an institution in San Fransisco who are now

established for the duration in the Childrens' Village at this War

Relocation Authority center for evacuees of Japanese ancestry. Mrs.

Harry Matsumoto, a University of California graduate, and her husband

are superintendants of the Childrens' Village where 65 evacuee orphans

from 3 institutions are now housed." (Manzanar, 07/01/1942)]

of

illness or incapacity; (2) dependents of

physically incapacitated evacuees; (3) orphans and other children under

18 without means of support; and (4) the heads of families which have a

total income from all sources inadequate to meet their needs. [PHOTO:

"Evacuee orphans from an institution in San Fransisco who are now

established for the duration in the Childrens' Village at this War

Relocation Authority center for evacuees of Japanese ancestry. Mrs.

Harry Matsumoto, a University of California graduate, and her husband

are superintendants of the Childrens' Village where 65 evacuee orphans

from 3 institutions are now housed." (Manzanar, 07/01/1942)]

Mess Operations

The job of feeding nearly 100,000 evacuees was unquestionably the biggest single task faced by the War Relocation Authority during the second quarterly period. It required more manpower than any other phase of the program, cost more money, and called for more detailed planning.

Menus at all centers were based on those prepared by the Subsistence Section of the Service of Supply Division of the Army. Approximate cost of food for evacuees averaged 45 cents per person per day. Staple products were purchased through nearby quartermaster depots of the Army in sufficient quantity to last for a period of 30 to 45 days. Perishable commodities were bought generally on the open market.

At all centers an attempt was made to satisfy both the Americanized tastes of the second-generation evacuees and the predominantly Oriental appetites of their alien elders. Fancy grades of provisions, however, were expressly prohibited and rationing restrictions on sugar (the only food rationed during the quarterly period) were strictly observed.

At all operating centers, special facilities were established for the feeding of babies, nursing mothers, invalids, and hospital cases. Because of the acute dairy shortages in the areas surrounding most of the centers, fluid milk was served ordinarily only to evacuees (such as mentioned above) who had a need for special dietary treatment.

Police and Fire Protection

With military police guarding the exterior boundaries of each relocation center, the War Relocation Authority took active steps during the quarter to set up police and fire protection activities within each operating community. Since these two fields of activity were second in importance only to mess operations, recruitment for the police and fire departments was usually started at each center immediately after arrival of the advance contingent. As subsequent contingents reached the center, recruitment was continued and training programs were initiated.

Although a policy covering internal security at the centers was not issued by the Authority until August 24, police departments at most centers were well on the road to organization prior to that date. Under the policy, the internal security force at each center is responsible for handling cases of misdemeanor while felonies are to be turned over to the proper outside authorities. Efforts were made during the quarter at all operating centers to establish patrols of evacuee wardens in three 8-hour shifts so that the communities would have constant police protection all around the clock. Violations of law and order at the centers during the period were confined mainly to misdemeanors.

In the field of fire protection, definite progress was made at all operating centers. During the quarter, three pumpers were received at Tule Lake; three at Colorado River; two at Minidoka; two at Gila River; and one at Manzanar. A Fire Protection Advisor attached to the San Francisco office of WRA visited all five of these centers, inspected the equipment, and assisted the center fire departments in the removal of fire hazards. At most centers, fire prevention programs of an educational type were launched, and by the close of the period plans were well under way for observance of National Fire Prevention Week. No serious fires occurred at any of the centers. Perhaps the most costly outbreak was a blaze at Tule Lake which caused a total property damage of around $4,000. A fire at Heart Mountain destroyed one of the laundry buildings.

Agriculture and Manufacturing

Although plans were made during the first quarter for rather extensive agricultural production and considerable manufacturing work at relocation centers, noteworthy progress in these two fields was possible during the second quarter only at the older centers and even there accomplishments fell somewhat below earlier expectations. Three main causes were responsible. First was the unsettled condition of the newer centers which compelled a concentration of attention on the primary job of community stabilization. Second was the exodus of many of the most able-bodied and productive evacuees for the sugar-beet harvest and other outside employment. Third was a very real shortage of adequate farm machinery and manufacturing equipment.

As the quarter ended, a few of the sugar-beet workers were beginning to filter back into the centers and others were expected in the later fall months. Adoption of the leave regulations, however, suggested the real possibility that many of the more productive evacuees would soon be leaving the centers permanently and that the agricultural and manufacturing programs should accordingly be revised further downward. Looking ahead to the future, it seemed distinctly possible that agricultural work at relocation centers might be confined largely to production of subsistence crops and that manufacturing work might occupy a considerably less prominent place than originally contemplated.

Religious Activities

A policy statement covering religious worship at the centers was issued by the Authority on August 24. Under this policy, evacuees of all denominations are permitted to hold services at the relocation centers and to invite outside pastors in for temporary visits with the approval of the Project Director and the community council. The Authority expressed a willingness, if construction materials should become available, to provide at least one house of worship for the use of all denominations at each relocation center. Qualified pastors among the evacuee residents are permitted to practice their religions and to hold services but are not entitled to work compensation from the Authority for such activities. They may, however, hold other jobs at the centers on the same basis as all other evacuees. During the quarter, no church buildings were constructed at any center and services were held generally in the recreation barracks. At most centers, interfaith councils composed of Protestant, Catholic, and Buddhist representatives were organized and programs of coordinated religious activity initiated.

Evacuee Newspapers

As evacuees poured into the centers throughout the summer, those with journalistic experience or aspirations and especially those who had worked on mimeographed newspapers at the assembly centers quickly set about organizing similar papers in their new localities. By September 30, newspapers or information bulletins of some sort were being issued regularly at all centers except the two in Arkansas and the one in Colorado.

During the first quarter, mimeographed papers had been established at Manzanar and Tule Lake. The Manzanar Free Press, dating back to mid-April when the center was still under WCCA management, was the first relocation center paper to change its format and become an independent journal. On July 22, the members of the Free Press staff, after negotiating with the manager of the Manzanar community store and the Chalfant Press in nearby Lone Pine, started publication of a four-page printed newspaper in tabloid form. In return for advertising space, the community store agreed to underwrite the cost of publication for a 90-day period. By the end of that period, it was hoped that the Free Press either would be self-supporting or could be incorporated into the regular consumer enterprise organization at the center.

All other relocation center papers being published at the close of the quarter were mimeographed and financed by WRA, but produced and edited by evacuee staffs. The Authority agreed to provide each center with a mimeographed paper until such time as a consumer cooperative association could be organized and could assume responsibility for publication of a journal. The newspaper staffs were permitted freedom of expression on matters relating to community affairs.

The following papers were being published at relocation centers at the close of the quarter:

| Name of Paper | Frequency of Issue |

|---|---|

| Manzanar Free Press | Three times a week |

| Tulean Dispatch | Daily |

| Poston Press Bulletin (Colorado River) | Daily |

| Gila News Courier | Twice a week |

| Minidoka Irrigator | Twice a week |

| Heart Mountain Information Bulletin | Twice or three times a week |

| Topaz Times (Central Utah) | Twice a week |

In addition, a mimeographed magazine designed to provide an outlet for evacuee literacy and graphic talents was being published monthly at Tule Lake.

Postal Facilities

To handle the large volume of incoming and outgoing mail,

special branch post offices were established at all operating centers,

usually within a few days after arrival of the first evacuee

contingent. These branch offices provided the residents with all the

regular postal services such as money order, mail registry, C.O.D.,

and

sales of United States war bonds. In addition, special sub-stations

were set up in available barracks by the evacuees at some centers to

handle distribution and collection of mail at various convenient points

within the community. At other centers, internal distribution and

collection of mail were handled by the block managers or by evacuee

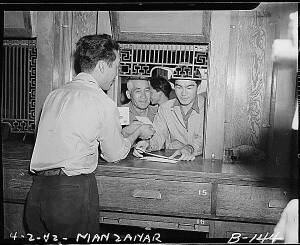

"mail carriers." [PHOTO: "Evacuees of Japanese ancestry receiving mail

at Manzanar Post Office - a branch of the Los Angeles Post Office, more

than 250 miles away. A two-cent stamp will send a letter by first-class

mail from Manzanar to Los Angeles." (04/02/1942)

to

handle distribution and collection of mail at various convenient points

within the community. At other centers, internal distribution and

collection of mail were handled by the block managers or by evacuee

"mail carriers." [PHOTO: "Evacuees of Japanese ancestry receiving mail

at Manzanar Post Office - a branch of the Los Angeles Post Office, more

than 250 miles away. A two-cent stamp will send a letter by first-class

mail from Manzanar to Los Angeles." (04/02/1942)

Evacuees handling mail were employed not by the Post Office Department but by the War Relocation Authority under the regular employment program at the centers. These employees consequently were not bonded and were not permitted to sell money orders, register mail, or handle sales of war bonds and stamps. All such postal facilities were available only at the one main branch office where non-Japanese civil service employees of the Post Office Department were on duty.

Official addresses for the nine centers opened prior to

September 30 are:

| Manzanar | Manzanar, California |

| Colorado River | Poston, Arizona |

| Tule Lake | Newell, California |

| Gila River | Rivers, Arizona |

| Heart Mountain | Heart Mountain, Wyoming |

| Minidoka | Hunt, Idaho |

| Granada | Amache, Colorado |

| Central Utah | Topaz, Utah |

| Rohwer Relocation Center | McGehee, Arkansas |

Individual Exclusion

During August and September, with the mass evacuation of people of Japanese ancestry virtually completed, the Army initiated considerably smaller-gauge programs on both the East and West Coasts which brought new responsibilities to the War Relocation Authority. These programs, carried out under the same authority as the mass evacuation (Executive Order No. 9066), were aimed at excluding from designated military areas any individual -- citizen or alien -- whose presence was considered dangerous to the national security. Such a program was announced for the eight States of the Western Defense Command on August 19 and for the sixteen Atlantic seaboard States of the Eastern Defense Command on September 10.

In connection with both programs, the Authority was called upon to assume responsibility for assisting in the relocation of the individual excludees. No attempt was made to provide special communities like the relocation centers where the excluded individuals could be temporarily quartered. Instead, the Authority merely undertook to assist them in making a purely personal type of transfer and adjustment. Once the excludee has become reasonably well settled outside the military area, responsibility for providing him and his dependents with any public assistance that may be necessary will rest with State welfare agencies and with the Bureau of Public Assistance of the Federal Security Agency.

Four types of assistance were contemplated by the Authority: (1) advice and information to the excludee regarding employment opportunities and desirable work localities in unrestricted regions; (2) transportation and subsistence during a temporary period of adjustment, usually not over four weeks; (3) assistance in connection with property problems; and (4) special guidance in connection with family difficulties. All those types of assistance will be made available only when requested by the excludee, and financial aid will be extended only in cases of actual need.

On the West Coast, the WRA end of individual exclusion was handled by the Division of Evacuee Property from its offices in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle. To handle the program on the Atlantic seaboard, special offices were established during the quarter at New York City and Baltimore and others were planned for Boston and possibly Atlanta.

Under arrangements conducted through neutral diplomatic channels, an exchange of nationals was effected during the summer of 1942 between the United States and Japan. On June 19, the Swedish Liner Gripsholm left New York Harbor with several hundred Japanese nationals aboard bound for the port of Lourenco Marques in Portuguese East Africa. At the African port the Gripsholm was met by two liners carrying American repatriates from Japan and Japanese occupied territory in the Far East; an exchange was effected, and the boats returned to their ports of departure.

Since the first sailing of the Gripsholm was given over largely to Japanese diplomatic representatives, consular officials, and their families and since it occurred during the midst of evacuation, only a limited number of West Coast evacuees could be included on the passenger list. Shortly before the sailing date, however, a number of alien evacuees whose repatriation had been requested by the Japanese government were interviewed at assembly and relocation centers and given an opportunity to book passage on the liner. A total of 47 people from various assembly centers and four from the Colorado River Relocation Center took advantage of this opportunity and were repatriated.

As the quarter ended, arrangements for repatriation of alien evacuees wishing to return to Japan on the next sailing of the Gripsholm (sailing date undetermined) were being handled by the Wartime Civil Control Administration in collaboration with the State Department. Plans were being made, however, for the War Relocation Authority to take over the responsibilities carried by WCCA on this matter some time in the fall after all evacuees had been transferred to relocation centers.

Organization and Personnel

With national headquarters established in Washington, the War Relocation Authority had three main field offices during the second quarterly period: San Francisco, Denver, and Little Rock. The San Francisco office provided general supervision and administrative services to the six westernmost centers or those lying within the area of the Western Defense Command. The Denver office, with a much more limited staff, furnished similar supervision and service to the Heart Mountain and Granada Centers; and the Little Rock office, with nothing more than a skeleton staff, was set up to direct the work at the two centers in southeast Arkansas.

In addition, offices staffed simply by one or two men plus stenographers were set up at Los Angeles and Seattle to handle evacuee property problems and individual exclusion and at New York City and Baltimore to handle exclusion alone.

As the quarter ended, the Authority had in Washington, at the principal field offices, and at the relocation centers a total payroll of 1,157 full-time, regular employees. Of this total, somewhere in the neighborhood of 40 per cent were teachers recruited for duty at the relocation center schools. The staff was distributed as follows:

| Washington | 74 |

| San Francisco | 214 |

| Denver | 23 |

| Little Rock | 14 |

| Manzanar | 97 |

| Colorado River | 4* |

| Tule Lake | 136 |

| Gila River | 125 |

| Heart Mountain | 115 |

| Minidoka | 69 |

| Granada | 106 |

| Central Utah | 56 |

| Rohwer | 46 |

| Jerome | 78 |

| TOTAL | 1,157 |

| * Bulk of staff on payroll of Office of Indian Affairs | |

A CHRONOLOGY OF

EVACUATION AND RELOCATION

July 1 --- September 30

-1942-

July 9 -- Evacuation of approximately 10,000 people of Japanese ancestry from Military Area No. 2 in California (eastern portion of the state) started, with movement direct to relocation centers instead of to assembly centers as in the evacuation of Military Area No. 1.

July 9 -- Opening of WRA regional office at Little Rock, Arkansas.

July 20 -- Adoption of WRA policy under which American-born evacuees who had never visited Japan were permitted to leave relocation centers for private employment especially in the Middle Western States.

July 20 -- Opening of Gila River Relocation Center near Sacaton, Arizona.

July 25 -- National Defense Appropriation Act including (among many other items) 70 million dollar appropriation for the War Relocation Authority for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1943 signed by President Roosevelt.

August 7 -- Evacuation of 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry from their homes in Military Area No. 1 and the California portion of Military Area No. 2 completed.

August 10 -- Arrival of first contingent of evacuees to open the Minidoka Relocation Center near Eden, Idaho.

August 12 -- Opening of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center near Cody, Wyoming.

August 18 -- War Department proclamation designating the four relocation centers outside the Western Defense Command as military areas issued by Secretary Stimson.

August 19 -- Announcement by Lt. Gen. J. L. DeWitt of a program under which any persons deemed dangerous to military security would be excluded from vital areas in the Western Defense Command.

August 24 -- Adoption of WRA policies on (1) internal security at relocation centers, (2) religion, (3) mess operations, (4) evacuee self-government, and (5) public assistance grants to evacuees.

August 25 -- Policy adopted by WRA providing for the organization of evacuee consumer enterprises at relocation centers.

August 27 -- Opening of Granada Relocation Center near Lamar, Colorado.

September 1 -- Adoption of WRA policy on employment and compensation at relocation centers. Main provisions: (1) free subsistence for all evacuee residents of the centers; (2) a wage scale of $16 a month for most evacuees working at the centers, $19 for professional employees, and $12 for apprentices; (3) clothing allowances for all working evacuees and their dependents; (4) automatic enrollment in the War Relocation Work Corps of all evacuees assigned to jobs at the centers; (5) establishment of Fair Practice Committee and Merit Rating Board within the Work Corps at each center; and (6) unemployment compensation for evacuees involuntarily unemployed.

September 10 -- Individual exclusion program for 16 states in the Eastern Defense Command announced by Lt. Gen. Hugh A. Drum, providing for the exclusion of "any person whose presence in the Eastern Military area is deemed dangerous to the national defense." The War Relocation Authority was authorized to assist persons excluded either from the Western or Eastern military regions to re-establish themselves in non-prohibited areas.

September 11 -- Opening of the Central Utah Relocation Center near Delta, Utah.

September 13 -- Order issued by Western Defense Command permitting evacuee workers at the Poston and Gila River relocation centers to enter certain parts of Military Area No. 1 in Arizona to assist in the harvest of the long-staple cotton crop.

September 15 -- Announcement made that the evacuee Property Division of WRA at San Francisco had set up branch offices in Seattle and Los Angeles and was responsible for the administration of evacuee property holdings valued at more than two-hundred million dollars.

September 17 -- Opening of Rohwer Relocation Center in McGehee, Arkansas.

September 21 -- Joint Resolution introduced in the United States Senate by Senator Rufus C. Holman of Oregon proposing amendment to the Constitution giving Congress the power to regulate conditions under which persons subject to dual citizenship may become citizens of the United States.

September 25 -- Offices of the War Relocation Authority opened in New York City and Baltimore to assist persons excluded from Eastern Military areas in finding work and homes in non-restricted areas.

September 26 -- Issuance of WRA regulations to become

effective October 1 under which any evacuee -- U.S. citizen or alien --

may leave a relocation center for temporary or permanent residence

outside the evacuated area provided four conditions are met: (1) the

applicant must have a definite offer of a job or some other means of

support; (2) there must be no evidence on his record to indicate

disloyalty to the United States; (3) he must agree to keep the

Authority informed of any change of job or change of address; and (4)

there must be evidence that he will be acceptable in the community

where he plans to make his new home.

EVACUEE ANXIETIES AND TENSIONS

Behind the outward appearance of activity and progress that prevailed during the summer at relocation centers, there were signs at most centers of growing community unrest. In the main, evacuee anxieties and tensions remained below the surface and were difficult to analyze or detect. But at two of the older centers, these feelings were more openly expressed and resentments boiled up in the form of "incidents."

Neither of these incidents involved physical violence. In both cases, the things that were said were far more important than the things that were done. But both occurrences were quite obviously manifestations of deep-rooted and chronic maladjustments and discontents within the community.

Incidents

The first of these manifestations occurred in the form of a meeting called together by some of the evacuees at one of the older centers on the evening of August 8. This gathering, held in one of the mess halls, was conducted entirely in the Japanese language and was attended by approximately 600 people. It was featured by strong arguments and sharp denunciations of living conditions at the center. Late in the evening the tone became so stormy that residents of nearby blocks were aroused and a member of the WRA administrative staff finally called upon the throng to disperse. The meeting broke up immediately thereafter but the incident left the whole community in a state of anxiety and nervousness that lasted for many days.

At another of the older centers, evacuee tensions reached a pitch in the last days of September when representatives of the Office of War Information visited the center with the suggestion that evacuee residents participate in making radio transcriptions on relocation center life for broadcast to the Far East. Shortly after the OWI men arrived at the center on the morning of September 28, the question of evacuee participation in the transcriptions was discussed at considerable length with the members of the temporary community council. The council members -- all of them American citizens and most of them in their early twenties -- were at first inclined to favor the project. On further deliberation, however, they decided that the matter should be submitted to a group of representative alien evacuees since the transcriptions were to be made in the Japanese language and would necessarily involve the participation of the alien residents. Accordingly, a joint meeting was arranged for the following morning between the council members and the predominantly alien block managers. This meeting, which lasted from early in the morning until 11 o'clock at night, was punctuated by frequent emotional outbursts and finally wound up with a decisive vote against participation in the transcription project.

Administrative Background

The fact that both of these incidents occurred at older centers is highly significant. Throughout the summer, while construction was going forward and evacuee contingents were being received at most relocation communities, the three centers established during the spring had passed through these phases and were in the process of settling down. Yet the relocation program had failed in some ways to keep pace with the development of these older centers. The War Relocation Authority, operating in a new and complex field of government administration where there were virtually no precedents or guideposts, was compelled to exercise extraordinary care in working out basic policies and procedures. Many of the most fundamental decisions were not made until the latter part of August. Meanwhile administrative staffs at the older centers were faced with the problem of managing rapidly maturing communities within a framework of policies that were only partially matured or wholly undetermined.

In terms of evacuee living, this situation, coupled with the shortage of materials, produced some highly undesirable results. As employment programs were gradually being developed, many of the older evacuees in particular were left without work. Men and women who had spent virtually their whole lives in hard physical labor found time hanging heavy on their hands. While fiscal procedures were being worked out and put into operation, those who did find jobs often went weeks and even months without pay. Recreation programs for the children lagged for lack of equipment. Construction of school buildings, described by the War Relocation Authority in an early pamphlet for evacuees as "one of the first jobs" to be accomplished at the centers, was held up by the shortage of materials. Under such circumstances, it is scarcely surprising that resentment was openly expressed. The really surprising fact, perhaps, is that these expressions were not more frequent and more intemperate in tone.

Yet it would be erroneous to ascribe the incidents that occurred wholly to administrative difficulties. Behind both of these incidents and similar (though less dramatic) manifestations even at the newer centers, there was a highly complex pattern of influences inherent in the very nature of the relocation program. Some of the more readily discernible of these influences are discussed in the following sections.

Cleavages in the Evacuee Population

At all the older centers as soon as the bustle and turmoil of the construction and induction period had died down, cleavages (some of which had existed long before evacuation) began to develop or reappear among the evacuated people. One line of cleavage already noted was between evacuees from the larger cities and those with predominantly rural backgrounds. Another and far more serious one was between the American-born younger generation (nisei) and their alien elders (issei).

This schism was carefully noted and described by an alien evacuee resident of one of the older centers. Highlights of his report on the subject are given below:

"The government of the United States has, in the process of evacuating the Japanese, made little, if any distinction between aliens of enemy nationality (issei) and American citizens of Japanese parentage (nisei). While these groups are racially alike, and are closely bound in family ties, their background and conditioning are as far apart as those found in any other immigrant group."The nisei, and here I am speaking of those citizens who have resided here since their birth and have received the major part of their education in this country, are conscious of their American way of thinking, and are imbued with ideals of American institutions. Before the outbreak of the present war, they had come a long way toward assimilation, politically and economically, if not socially, into the American scene. They were just arriving at a stage where they can assert independence from the family control by the issei.

"The issei's stand in this war, with few exceptions, has been that of passive non-resistance. They have faithfully conformed to all government regulations concerning aliens of enemy nationality during wartime. They have shown..... willingness to work and cooperate with the administration. Whatever grievance they may have, they have never expressed it openly to the administration. Therefore, it is very difficult for the administration of this camp to determine the attitude and reactions of its issei population.

"The nisei as a group are dissatisfied with the treatment they have received from the government. They are disillusioned -- bitter. Many of them are frustrated and desperate..... It is a known fact that we have in the camp today certain elements who are working upon the bitterness of the nisei. These individuals are making agitational talks privately and publicly to whip the nisei sentiment into an anti-American mob hysteria. They are finding a ready response from many dissatisfied nisei.

"I am convinced, based upon my observation, that there are certain irreconcilable differences between the issei and nisei -- namely, the question of attachment to their respective countries. Of course, every immigrant stock faces a conflict between the first generation with its old world ideals, philosophy and customs and the second generation to become extremely Americanized. The Chinese, the Irish, the Italians, and the rest have gone through this experience. The only marked, but extremely important difference with the Japanese, is that at the present time this generation-conflict is closely tied up with the question of loyalty, since Japan and the United States are at war.

"There are some issei, who are technically enemy aliens, but are just as loyal and more so than many nisei..... These individuals, for the most part, have arrived in this country when very young and have been educated and raised as Americans. Were it not for the act of Congress forbidding their naturalization, they would have become citizens long ago. There are a few others, who, because of political convictions, were anti-fascist even before the outbreak of the present war, and can contribute substantially toward the American war effort and are anxious that they be called upon to perform some service to this country. They are, in a sense, in a same category as German refugees in this country."

The fact that the writer of this statement is himself an alien of course lends additional weight to the point he makes in his final paragraph. In this connection, the comment of a trained observer at one of the relocation centers is highly pertinent. "It is natural," he writes, "that the older people, the native born Japanese, should have a sentimental attachment to Japan. There can be little doubt that the great majority of them do have such feelings, and that they deeply enjoy their own music, songs, drama, traditions, and customs. This enjoyment is probably increased and sought as a refuge under the present circumstances of suffering..... loss of income and possessions, and fear of the future. This is not the same thing as pro-Axis plotting, but rather the up-surge of sentimental feelings mixed with a certain childish defiance in people who in their calmer moments are perfectly willing to be 'neutral enemy-aliens' and collaborate with the Government."

Feelings of Fear and Insecurity

Perhaps the most common emotion noted among the evacuated people during the second quarter was a profound feeling of insecurity or rootlessness. This feeling, which was probably an inevitable result of evacuation and of living conditions at the centers, was manifest at all but the very newest relocation communities.

Fear About the Post-War Future

The overwhelming fear of the evacuees -- the one which most deeply influenced their efforts toward adjustment -- was their anxiety about the post-war future. Younger evacuees in particular were frequently heard asking questions such as : "Where shall we go from here after the war?" "How shall we earn a living?" "What will be the long-time effect of life here upon our character, and how will we be affected in our future adjustments?" Against the background of the immediate past, very few even among the American-citizen evacuees were able to provide themselves with encouraging answers for these questions.

While the younger residents worried about occupational status, the older evacuees were more inclined to fear the effects of relocation life on family savings. Families which entered the centers with only a few hundred dollars savings -- and often far less -- were constantly uneasy about the prospect that they would spend more money at the centers than could be justified in the light of future family needs. The result was an increase in intra-family bickering and a tendency on the part of many to resist the formation of certain consumer enterprises and other undertakings that would encourage family spending.

Fears About the Breakdown of Family Authority

Almost every aspect of relocation center life -- the mass feeding, the close quartering, the thin partitions between family compartments, the occasional doubling up of small families in a single compartment, the absence of normal economic opportunities -- tended almost inevitably to disintegrate the pre-war structure of evacuee family life. Housewives, freed of all responsibility for family cooking and largely relieved of other household burdens, began to assert themselves more openly and sought about to find new outlets for their energies. This tendency was particularly disruptive among the older people since the housewife in Japanese society has traditionally occupied a distinctly inferior status. At the same time, however, these housewives and mothers were themselves profoundly disturbed by the lessening of parental authority over the children. Along with the fathers, they frequently voiced concern about the bad table manners, the increasing frivolity, and even the occasional insolence which they had noted in their sons and daughters since the arrival at relocation centers. The teen-age youngsters of Japanese ancestry, who had established an admirably low record of juvenile delinquency in their former homes on the Pacific Coast, showed a marked tendency toward rowdiness in relocation centers. And in more than one center, the formation of rather distinct juvenile "gangs" was noted. The effect of all these trends particularly on the minds of the older people trained in Japan -- where the sanctity of family ties is tremendously significant -- can scarcely be overstressed.

Fears About Food

The fear of food shortage was directly related, on the one hand, to the kind of food served in the mess halls, and on the other, to the anticipation of transportation difficulties due to bombing or winter stalling. Whenever the meals were poor, the people exhibited anxieties of food shortage, and even went to the extent of looking into the warehouses. This concern about a prospective food shortage also arose from the popular conception about railway problems of snow-covered passes and bombed out tracks, a conception that was reinforced by the minor difficulties actually experienced at some of the centers. Women in some centers took to drying leftover rice in the sun with the thought that it might be saved for the day when there would not be "enough to eat in the mess halls."

Fear of Violence

Some instances of physical violence occurred at the older centers, and reports on them spread widely and rapidly with the usual exaggerations of details. Many who were leaders in their former communities were reluctant to assume positions of responsibility at the centers because of their fear of difficulties with fellow members of the community, or even of violence from them. Persons who did assume responsibility were frequently threatened and in some cases actually beaten. Agitators and individuals given to violence appeared more frequently among the bachelor aliens and the American-born evacuees educated in Japan, but the tendency was not absent (as already noted) among the youngsters born and reared in this country.

In view of the WRA aim to encourage employment of properly qualified evacuees outside relocation areas, perhaps the most disturbing of all the fears exhibited by evacuees during the second quarter was their grave apprehension about the American climate of public opinion. This feeling, of course, was not without foundation. During the period of voluntary evacuation in March of 1942, migrating families of Japanese descent were sullenly received and even threatened with mob violence in many communities of the intermountain States. Even after voluntary evacuation had been prohibited, high public officials and organized groups continued to voice sentiments of wholesale animosity against all people of Japanese origin regardless of birth, upbringing, or individual attitudes. In editorial columns, and in the "letters to the editor" of many an American newspaper, the evacuees found a dominant tone of hostility and condemnation directed toward them. In some quarters, there was talk of mass deportation to Japan at the close of the war.

By the close of the summer, with thousands of evacuees out in the beet fields, these feelings had begun to be modified in many localities. But the prevailing temper of public opinion as it reached the eyes and ears of the evacuees was still basically hostile. And the evacuee fear of public reaction was perhaps the most serious single obstacle to optimum utilization of evacuee manpower both inside and outside the relocation centers.

Conclusion

Many of these anxieties and tensions, of course, arose from the very newness of the relocation program and from the fact that evacuees had been plunged into a situation unlike anything they had ever experienced before. In the future, as the relocation centers lose some of their pioneer character and as policies and procedures become better known and more firmly established, many of the apprehensions which loomed so large in evacuee minds during the summer of 1942 will perhaps be replaced by confidence based on experience.

It was clear, however, by the close of the second quarter that there are many aspects of relocation center life which will probably continue to cause unrest as long as the centers remain in operation. Relocation center life, by its very nature, will probably never provide sufficient opportunity and incentive to the younger and more capable evacuees, and it is quite likely in some cases to have a long-range demoralizing effect.

In the light of such considerations and in view of the

national manpower situation, the leave regulations which became

effective on October 1 take on additional point and purpose. Under

these regulations, the best qualified evacuees, who are usually also

the most restive under the restrictions of relocation center life, will

presumably be among the first to leave. The net long-range effect

should be salutory both for the relocation centers and for the nation

as a whole.

SUMMARY REPORTS ON THE CENTERS

Manzanar

Oldest of all the relocation centers, dating back to

March 23

(as a reception center under the WCCA), Manzanar in the Owens Valley

section of California had by September 30 taken on many of the aspects

of a settled community. In place of the dust and bareness of late

March, there were hundreds of green lawns around the barracks

and Victory gardens in the firebreaks. Family living quarters,

originally

laid out in all barracks to accommodate a "standard" family of seven

persons, had been improved and reconstructed so as to accommodate

families of varying sizes. A printed newspaper, the only one at

relocation centers, was appearing in four-page tabloid form three times

a week. A 250-bed hospital, staffed by six doctors and five

registered

nurses, was efficiently caring for the health needs of the

community. A

cooperative enterprise association, incorporated under the laws of

California, had taken over management of the general store and canteen

and was in the process of setting up a barber shop, beauty parlor,

shoe

repair establishment, and motion picture theater.

Of the 9,057 evacuees actually in residence on

September 30,

more than 4,000 -- or approximately 80 per cent of the

employables --

were engaged in full-time jobs at the center. By far the greatest

number, 1,503, were working in the dining halls and kitchens on

the

enormous job of feeding the entire community. Some of the American

citizens were occupied on the garnishing of camouflage nets for

the

Army, others, aliens as well as citizens, took part in the manufacture

of garments for residents at all relocation centers, the production of guayule

plants, and a variety of community service jobs

ranging from

the copy desk of the newspaper to the collection of community garbage.

By the close of the quarter, more than 1,000 men and 30 women evacuees