-- Page 6 --

WAR RELOCATION CENTERS

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 27, 1943

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 27, 1943

UNITED STATES SENATE,

SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON MILITARY AFFAIRS,

Washington, D. C.

SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON MILITARY AFFAIRS,

Washington, D. C.

The subcommittee met, pursuant to adjournment, at 11:10 a. m., in the Military Affairs Committee room, Capitol Building, Senator Albert B. Chandler presiding.

Present: Senator Chandler, Senator Murray, Senator Gurney, Senator Holman, and Senator Lodge.

Also present: Senator Johnson of Colorado, George W. Malone, Special Consultant to the Committee.

STATEMENT OF REX L. NICHOLSON,

REGIONAL

DIRECTOR,

FEDERAL WORKS AGENCY FOR THE 11 WESTERN STATES,

SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH

FEDERAL WORKS AGENCY FOR THE 11 WESTERN STATES,

SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH

Senator CHANDLER. Mr. Nicholson, will you state your name, your address, and with whom you are presently connected?

Mr. NICHOLSON. I am the regional director of the Federal Works Agency for the 11 Western States.

Senator CHANDLER. On March 30, 1942, Mr. Nicholson received a letter from J. L. DeWitt, lieutenant general of the U. S. Army, and now western defense commander, and the letter is as follows:

MY DEAR MR. NICHOLSON:Now, Mr. Nicholson, if you will just explain briefly, and then give us an opportunity to ask questions, your connection with this project, we will be very grateful, sir.

Assembly centers and reception centers have been and are being established in connection with the evacuation of German, Italian, and Japanese enemy aliens and persons of Japanese ancestry from restricted zones within military areas established by my Military Proclamations No. 1, March 2, 1942, and No. 2, March 16, 1942, under authority granted to me by the President's Executive Order No. 9066, February 19, 1942.

It is requested that the Federal Works Agency, Work Projects Administration, region 7, assume the responsibility for the management of the assembly centers and reception centers established in the western theater of operations. In performing the necessary management services you are authorized to incur obligations and make expenditures from any funds available to your agency, or made available to it by the War Department.

As the above functions will involve the expenditure of funds, it is requested that you submit at the earliest practicable date a Budget estimate of fiscal requirements to and including April 30, 1942. The estimate submitted should be in sufficient detail that will show various operational costs at each center on a per thousand evacuee basis.

Direct communication with Col. K. R. Bendetsen, Assistant Chief of Staff, Civil Affairs Division, is authorized in formulating general plans and policies of management.

J. L. DE WITT,

Lieutenant General, U. S. Army.

Mr. NICHOLSON. On March 6 I was in Washington, D. C.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. What year?

Mr. NICHOLSON. 1942. I received a call from Assistant Secretary McCloy's office asking me to come over there for a meeting. I went over there, and we had a brief meeting with the Assistant Secretary and some members of the staff and some of the other Federal agencies.

He asked me what I knew about the Japanese situation in the West, and I told him I knew nothing except what I had been reading in the papers.

He said it had been suggested to him that the W. P. A. organization out there was perhaps the best equipped agency to handle the management of these assembly and reception centers, and wanted to know whether or not it was possible for us to assume the responsibility for the job.

I was unable to give him a definite confirmation of our acceptance of the responsibility at that time, until I had had an opportunity to confer with the Commissioner and also to discuss the problem and the details with General DeWitt.

I took a plane that evening and flew out to San Francisco and had a meeting with General DeWitt and his staff and several members of other Federal agencies operating in the field.

After this conference we agreed to assume the responsibility for the management of all assembly and reception centers established for the evacuation of the Japanese. It was to be a temporary function, pending the organization of the War Relocation Authority and their getting themselves in shape to accept the Japanese and transfer them inland.

We were asked to furnish administrative staffs for each center to assume complete responsibility for all management inside the center. The Army did not go inside except on inspection trips. We assumed that responsibility, and I sat down at a desk in San Francisco, on March 12, and we immediately attacked the problem.

Senator CHANDLER. Detail to the committee, in your own words, your experience with this, and then make whatever observations you would like to make concerning the problem.

Mr. NICHOLSON. Well, I think I should say in the beginning that, from a standpoint of difficulties, it was one of the toughest administrative problems we had ever tackled up to that time. It had to be done very rapidly.

When we got out there the military proclamations had already been issued -- one of them issued on March 2 and the other issued on March 16 -- requiring the evacuation of a large number of the Japanese before that month ended. The Army engineers had started construction on one reception center up in Manzanar, in Owens Valley.

I made a trip to that center immediately after taking over in San Francisco, and we found that there was not even any lumber on the job yet, and 15 days later we were supposed to receive some Japanese there and house them.

Well, the Army engineers practically worked a miracle. They were able to get some buildings up, although they did not get doors and windows in them. However, we took the Japanese in. We received a large number of them on the date on which the general had ordered them out, and during the interim we had equipped the center with the proper equipment -- feeding and housing equipment -- staffed it, and we received the Japanese when they arrived and served them a hot meal.

Senator GURNEY. On what date, if I may ask?

Mr. NICHOLSON. I could not tell you the exact date. I would have to check the exact date.

Senator GURNEY. About April 1?

Mr. NICHOLSON. It was about April 1.

Senator CHANDLER. How long did you keep them under your charge?

Mr. NICHOLSON. They were under our charge until they were all evacuated to the War Relocation Authority. The last evacuation was about the 1st of November.

Senator CHANDLER. Did you sever your connection with it then?

Mr. NICHOLSON. No. We still have a small staff out there working under General DeWitt's direction, cleaning up the property, disposing of the property, cleaning up the records, and so forth; but we have no further connection with the Japanese themselves.

Senator CHANDLER. Were you offered the position to continue? If you want to answer this off the record, I want you to answer, because I want you to tell the committee about this frankly.

(There was a discussion off the record, after which the following occurred:)

Senator CHANDLER. Is it your opinion that there are many of those Japanese there who are enemies of the country, almost irreconcilably, who are in these relocation camps, who ought to be gotten out and segregated and put to themselves?

Mr. NICHOLSON. We recommended segregation.

Senator CHANDLER. Has that been done?

Mr. NICHOLSON. I do not believe it has, although I am not sure. I have had very little contact with them recently.

Senator GURNEY. What percentage of the total would you figure in that class?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is pretty hard to say. I think the Federal Bureau of Investigation could come nearer to answering that question than I can. They know the situation very well.

Senator GURNEY. You must have some ideas on it. Could you give us your best judgment on it? Would it be all the aliens, which would make up a third of them?

Mr. NICHOLSON. No; it is not. I would say it would be somewhere between 5 and 10 percent of those who were evacuated from the large metropolitan centers who are bad hombres. They are dangerous.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. Will you give us some of the details as to why you consider them dangerous? In what respect are they dangerous and what is the nature of the danger from them?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Well, we immediately found attempts right from the start -- this I would prefer to have off the record, if you please.

(There was a discussion off the record, after which the following occurred:)

Senator GURNEY. That ought to be in the record.

Mr. NICHOLSON. We found that there was a small percentage of the Japanese evacuated from the large metropolitan centers that was given to underworld practices. They attempted to bootleg liquor into the camps. They also attempted to start gambling rings. They also attempted to foment trouble among the satisfied Japanese.

Senator CHANDLER. How did you handle that?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Well, we had a staff of civilian police on the inside, and we were just as tough as we needed to be to stamp it out.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. Did you put them in jails?

Mr. NICHOLSON. We had places where we could lock them up when they failed to comply with the regulations.

Senator CHANDLER. Did you ever have any trouble with them as regards discipline while you had them?

Mr. NICHOLSON. No.

Senator CHANDLER. You did not have any trouble?

Mr. NICHOLSON. No.

Senator CHANDLER. But you issued orders for their governments.

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct.

Senator CHANDLER. And you did not deal with committees?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct.

Senator CHANDLER. You think that is the only way that you can handle a situation like that?

Mr. NICHOLSON. I certainly believe it is the best way, Senator.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. What about the loyalty of this percent of underworld characters that you found among the evacuees? What is their loyalty to the country?

Mr. NICHOLSON. I think it is very questionable.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. Did you find any loyalty to Japan among the evacuees and any disloyalty to the United States?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Well, it was awfully hard to identify. They are pretty shrewd. We felt certain in our own minds that it was there.

Senator GURNEY. May I ask you, Mr. Nicholson, this question? You took over about March 6 or March 12, and you got your first evacuees around April 1?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Sometime early in April, Senator. I do not remember the exact date.

Senator GURNEY. The approximate date is all I am interested in. That was by the establishment of one camp. When you passed over the administration to the War Relocation Authority how many camps did you have?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Sixteen.

Senator GURNEY. Do you know how many there are in existence now?

Mr. NICHOLSON. I am not sure that I do. They are scattered from Arkansas west.

Senator GURNEY. Are there more than 16, Mr. Chairman? Do you know?

Senator CHANDLER. There are either 10 or 12.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. There are different kinds of camps?

Mr. NICHOLSON. They are larger than the temporary assembly centers we had them in.

Senator GURNEY. Some of the 16 that you were administering have been done away with and put into larger units; is that right?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Well, all of the 16 temporary assembly centers have been completely evacuated. There are no Japanese in them.

Here is what we had to do. It was the plan in the beginning to move them right into these permanent centers inland, but we found that we did not have time to locate the proper center and to build the facilities to house them, so it became necessary to go out and take over race tracks and fair grounds where there were utilities already installed -- light, water, heat, power.

The Corps of Engineers went in and built 16 of those places in 3 weeks. We staffed them just as fast as they got the buildings up, and as soon as the contractor was out of the way we started feeding the Japs right in.

Senator HOLMAN. May I comment at this point?

Senator CHANDLER. Yes.

Senator HOLMAN. You give the impression that you built new buildings and new barracks. In some cases the facilities already present were remodeled; is that not so?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct.

Senator HOLMAN. With a contract that at the conclusion of their use they would restore them to the original condition; is that right?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct, except ---

Senator HOLMAN. I think it would be well for the record to have the cost of that remodeling up to now and the ultimate cost to be made.

Senator CHANDLER. Do you have that?

Mr. NICHOLSON. I do not have that, Senator. You will have to get that from the Corps of Engineers.

Senator HOLMAN. While we are on that subject, I have the number and size of these various stations. It has been supplied to me, and I will furnish it for the record, if you wish.

Senator CHANDLER. It is in Mr. Myer's testimony, I think. It is in the record.

Senator HOLMAN. I am a little confused about the relation of the hearing we had the other day to this.

Senator CHANDLER. This is a continuation.

Senator HOLMAN. It is a continuation?

Senator CHANDLER. Yes.

Senator HOLMAN. Then, there is one question I wanted to obtain an answer to. It was the schedule of positions, with the title of each position, and the compensation attached to that particular title.

Senator CHANDLER. Senator, we will get that, but Mr. Nicholson has not been able to supply that, because he is not presently connected with that at all. We are concerned today with the history of it.

Senator GURNEY. May I continue, Mr. Chairman?

Senator CHANDLER. Yes.

Senator GURNEY. When did you discontinue your services with these Japanese centers?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Well, we started evacuating them to the permanent relocation centers in July, and we continued that process just as fast as the War Relocation Authority could get their centers ready. We made the last evacuation the latter part of October and the first of November.

Senator GURNEY. And you remained in control of the Japanese evacuees in these temporary places until you sent them over to the permanent places?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct.

Senator GURNEY. Which now number 12 permanent camps; is that correct?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct.

Senator GURNEY. And that is the way you become released from your responsibility?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct.

Senator GURNEY. As they were ready to take them, you sent them on to the permanent places, and then you were out from under; is that correct?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. As I understand it, there were 16 assembly centers, and the evacuees were sent to those 16 assembly centers, and then they were sent from the assembly centers to the more or less permanent Japanese colonies -- they call them colonies -- such as we have at Granada, Colo. There is a colony there.

Now, the assembly center is where you had jurisdiction?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That was the temporary housing for them.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. They first brought the evacuees in to the temporary housing, and you were in charge of those assembly centers, were you not?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. Then they passed on to the colonies, and as they went to the colonies, W. R. A. took them over?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct, except that we had one permanent center. We had the big relocation center in Manzanar, Calif.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. That was retained as a colony?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct. It was the first one to which we evacuated the Japanese.

Senator CHANDLER. That is where they had a riot not so long ago?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Yes; that is correct.

Senator CHANDLER. Are you familiar with the facts and circumstances concerning that riot?

Mr. NICHOLSON. No.

Senator GURNEY. Mr. Nicholson, you had the first responsibility? That is, the Army turned them over to you. Did you have any trouble with separation of families? Did the family come to you as a unit, or was it separated by the Army?

Mr. NICHOLSON. No; it came to us as a unit.

Senator GURNEY. Was the Army very careful to be sure that they were not separated?

Mr. NICHOLSON. There was great care exercised to see that the family unit was held intact.

"Members of the Mochida family awaiting evacuation bus. Identification tags are used to aid in keeping the family unit intact during all phases of evacuation." (Hayward, 1942)

Senator GURNEY. Were all the uncles and aunts brought in with the family, too?

Mr. NICHOLSON. No. In some cases there was a separation of the distant relatives.

Senator GURNEY. Did you later try to get them together?

Mr. NICHOLSON. We tried to get them together as near as we could. In some cases it could not be done because of lack of space, but wherever we possibly could we put them together when they requested it.

Senator GURNEY. And you did allow them an opportunity to say, "My aunt or uncle or cousin," and so forth, "is in another camp and we would like to have them here or we go there"; is that correct?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. What about work? Did you provide any work within the assembly centers?

Mr. NICHOLSON. We provided all the work possible under the circumstances. It was difficult in some of the centers to provide work for all of them, because we did not have the facilities with which to work them, but wherever we could we did private work; and we found that it was a tremendous advantage in management of the Japanese to have them working 8 or 10 hours a day.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. Are they good workmen?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Excellent.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. What work did you have them do?

Mr. NICHOLSON. We had them assigned to all of the tasks in connection with the actual operation of these centers. It involved all kinds of mechanical and

menial labor. We had to have the upkeep of the light

plants and the plumbing and the repair of the buildings.

menial labor. We had to have the upkeep of the light

plants and the plumbing and the repair of the buildings.In some cases the Japanese themselves made the furniture they used in their barracks, and did a nice job of it, too. [PHOTO: "Shinkichi Kiyono, 56, evacuee from Longview, Washington, exhibits the cabinet which won for him first prize (a carpenter's plane) in a furniture building contest. All pieces of furniture were made from scrap lumber." (Tule Lake, 07/01/1942)]

Then we did a large job of fabricating camouflage nets for the Army. This was the type of hand work that could be done very nicely in those centers where we had large enough sheds where the nets could be hung for fabrication.

Senator CHANDLER. Did you have any trouble when you assigned one of these Japanese to a task?

Mr. NICHOLSON. No.

Senator CHANDLER. You did not ask them whether they wanted to do it or not?

Mr. NICHOLSON. No. We just assigned them to the responsibility that we wanted them to take.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. They were industrious and dependable and did a good job?

Mr. NICHOLSON. I would say they were exceptionally so, Senator.

Senator MURRAY. They showed no resentment at being directed to do anything?

Mr. NICHOLSON. No. That is all they understand.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. What pay did they receive?

Mr. NICHOLSON. This will be subject to checking the record, but, as I recall it, we had a pay established of $12 per month for unskilled labor.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. Plus maintenance, of course?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Plus maintenance and subsistence in the center.

There was a $15-per-month pay for semiskilled labor and $19 a month for skilled or professional labor. The doctors who manned our hospitals received $19 a month for that service.

Senator GURNEY. Were they able to supply all the medical care necessary?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Yes.

Senator GURNEY. You did not have to bring any white people in?

Mr. NICHOLSON. We did not need to bring white people in for any task except actual management. We found the proper skills to do all of the work.

Senator GURNEY. May I ask you, Mr. Nicholson, did you search any of these evacuees as they went into the relocation centers?

Mr. NICHOLSON. They were all searched by the military authorities as they went in.

Senator GURNEY. As the operation of the camp continued, did you allow them to pass outside the gates and come back in again?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Only when they were accompanied by a guard.

Senator GURNEY. And so there was no chance of their bringing any firearms into the camp while you were in charge?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Absolutely none.

Senator GURNEY. You made sure of that?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That was our responsibility.

Senator GURNEY. And the same on liquor?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct. No package came into the center without first being inspected.

Senator GURNEY. Was their mail censored?

Mr. NICHOLSON. No.

Senator GURNEY. Their mail was not censored?

Mr. NICHOLSON. They were allowed free mail, but any package that came in, whether it be mail or whether it was sent by some individual outside, was inspected before it was delivered.

Senator GURNEY. Was there any control set up for their bank accounts, their money?

Mr. NICHOLSON. No control. We made provision for them to have

banking

service in the centers through regular banks. They sent

armored cars into the centers for acceptance of deposits and for the

handling of the Japanese accounts; and each bank in the vicinity of one

of those centers was accorded that privilege if they desired it.

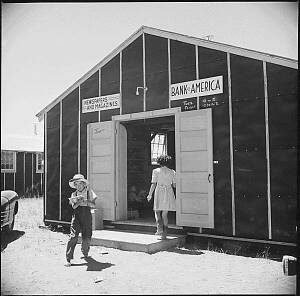

[PHOTO: "A view of the bank and newsstand at this War Relocation

banking

service in the centers through regular banks. They sent

armored cars into the centers for acceptance of deposits and for the

handling of the Japanese accounts; and each bank in the vicinity of one

of those centers was accorded that privilege if they desired it.

[PHOTO: "A view of the bank and newsstand at this War RelocationAuthority center for evacuees of Japanese ancestry. The bank is open on Tuesdays and Fridays only." (Tule Lake, 07/01/1942)]

Senator GURNEY. And if a Japanese wanted to continue his back account in Los Angeles, say, he could?

Mr. NICHOLSON. He was permitted to do that by mail; yes.

Senator GURNEY. You had some rich Japanese in there and some poor ones, did you not?

Mr. NICHOLSON. We had some very wealthy people in those places.

Senator GURNEY. You still have? I mean, they undoubtedly are still there?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct.

Senator GURNEY. So they conceivably write checks and send them to whomever they wished anywhere in the United States?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct. The only censorship that was ever exercised was on foreign correspondence.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. Would you mind discussing the different kinds of Japanese, and more particularly with respect to their loyalty to this country and their loyalty to Japan, in your opinion? I would like to have a frank statement of your own opinion as to the loyalty of the different kinds of Japanese. The Japanese can be separated into several classes.

Mr. NICHOLSON. Well, that was a hard question to determine, as you might well guess.

Of the groups, we have the American-born Japanese who was educated in this country. He is the Nisei. Then we have the American-born Japanese who was educated in Japan. He is the Issei [NOTE: Should read Kibei]. Then we have the foreign-born Japanese who was educated in Japan. They called him the Kibei [NOTE: Should read Issei].

Of the American-born, American-educated Japanese, I think there were very few who were disloyal, if any. Their loyalty to the United States was quite pronounced among that group.

I think the loyalty of the American-born Japanese, educated in Japan, is very questionable.

I also think the Japanese-born [NOTE: Should read American-born], Japanese-educated Kibei are questionable, but I think there are some loyal people among them.

Senator GURNEY. Didn't you misstate yourself there? You said that the loyalty of the American-born, American-educated was questionable?

Mr. NICHOLSON. No. I said that it was unquestionable, Senator.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. And the American-born, Japanese-educated are questionable?

Mr. NICHOLSON. They are questionable, that is right.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. What are the percentages of the three classes, approximately?

Mr. NICHOLSON. I do not know exactly. I would have to refer to the record to be exact, but about 55 percent of them are citizens of this country. About 20 percent, I would say, are Japanese-born, Japanese-educated. Those are only approximate figures. I have the record, but I do not remember exactly what it is.

Senator MURRAY. Was there any practice of sending any of these American-born, American-educated Japs back to Japan for finishing their education? I thought I had understood from some articles that I had read that they had sent some of these American-born Japs over to Japan.

Mr. NICHOLSON. Yes, there were a number of them that went back to Japan after they were educated in this country and took some additional schooling there and then returned.

Senator MURRAY. Were they not affected by their Japanese training or education that they received over there?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Some of them were, I think.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. What about their religion? Some of them are Shintos and some Buddhists?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Yes.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. What about those particular religions?

Mr. NICHOLSON. We allowed them to have their regular services in the centers. If there were Buddhists, who wanted to worship in their own way, we permitted them to do that, and the Catholics were permitted to worship in their own way, and the Protestants were permitted to worship in their own way.

Senator GURNEY. What percentage of those Japanese are Christians, Protestants, or Catholics?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Well, it follows pretty closely along the line of citizenship, Senator.

Senator GURNEY. Then, 55 percent would probably adopt the religions that we know in this country?

Mr. NICHOLSON. I would say it would run pretty nearly that high among them; yes. They surprised me. They were quite zealous about their worship, and that applied to all of the groups.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. And the Christian Japanese were more or less good, loyal citizens?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Yes.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. In your opinion, does their loyalty more or less follow their religious belief to some extent?

Mr. NICHOLSON. I do not believe that would be true, Senator. We found Christians among the alien groups and also we found Buddhists and Shintos among the citizens; but, generally speaking, your statement would be true.

Senator CHANDLER. Did you find Shintos loyal to the United States?

Mr. NICHOLSON. I think that is questionable.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. I do not see how they could be, with the Emperor the head of the church.

Senator CHANDLER. The F. B. I. head at San Francisco does not think Shintos are loyal to the United States. He thinks they are bound to strike at the Government, and I agree with him, from what I have heard. I think it is highly questionable. Is that not true?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is true.

(There was a discussion off the record, after which the following occurred:)

Senator CHANDLER. What is your idea of undertaking to govern these camps by establishing Japanese committees inside the camps to make rules for their own government?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Well, we started that and we abandoned the practice.

Senator CHANDLER. Why did you abandon it?

Mr. NICHOLSON. It did not prove satisfactory.

(There was a discussion off the record, after which the following occurred:)

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. On the record, did you, in handling this problem, work closely with the F. B. I.?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Yes. The F. B. I. was right in the picture all the time. They were on call any time they were needed, and did some very excellent work in connection with the whole problem.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. They gave you every cooperation?

Mr. NICHOLSON. Every assistance that we needed.

Mr. ALAN JOHNSTONE (General Counsel of the Federal Works Agency). Mr. Nicholson, did you think these people should be let out of these places except under guard?

Mr. NICHOLSON. This is off the record again.

(There was a discussion off the record, after which the following occurred:)

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. I would like to make a very brief statement for the record, and I would like to have Mr. Nicholson listen to it and perhaps comment on one phase of it.

At Granada, Colo., and at Heart Mountain, Wyo. -- two of the colonies, one in Wyoming and one in Colorado -- the W. R. A. undertook to contract school buildings for the two colonies, $308,000 at Granada and over $400,000 at Heart Mountain.

In the contract they stipulated that all labor would be outside labor; that no labor would be Japanese labor. They gave as their excuse that you could not mix the two, that you could not mix union labor on the outside with Japanese labor on the inside; and so, to get around that, they simply let a contract to an outside contractor to come in and build these buildings -- rough, temporary school buildings -- costing, as I say, $308,000 in one instance and $400,000 in the other. They gave as their excuse that they did not have workmen among the evacuees sufficiently skilled to do this work.

I took that matter up with Granada, and a Japanese out there sent me this {indicating} to prove what he could do in the way of skilled work.

A friend of mine went to the Granada camp, and he did not have very good facilities for acquiring this information, but he found that they have 6,800 native evacuees at that colony and he found that they had 7 cabinetmakers, 33 carpenters, 43 handy men, 12 plumbers' helpers and plumbers, and 7 electricians and electricians' helpers.

I wanted to ask Mr. Nicholson if he thought that that was about the proportion of skilled workmen that you would have in that number. Of course, we want to remember that these buildings are temporary buildings. They are just simply thrown together. I wanted to ask him whether or not in his opinion these evacuees could construct such buildings.

Mr. NICHOLSON. We had no difficulty in finding any skill that we needed. We constructed some temporary-type buildings, and we always used Japanese for that work. We had no difficulty whatsoever.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. Do you think this classification sounds reasonable?

Mr. NICHOLSON. What is the capacity? Seven thousand?

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. Seven thousand, and there are 7 cabinetmakers, 33 carpenters, 43 handy men, 12 plumbers' helpers and plumbers, and 7 electricians and electricians' helpers.

Mr. NICHOLSON. That might have been the proportion that was so classified, but I am sure you could have found many more in each one of those classifications that could have done that work satisfactorily. That was our experience.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. I noticed you said that they made their own

furniture, so that would indicate that they were skilled?

furniture, so that would indicate that they were skilled?Mr. NICHOLSON. That is correct. [PHOTO: "The Ninomiya family in their barracks room at the Amache Center. The mother's handiwork in preparing drapes, fashioning furniture out of scrap material, plus the boys' ingenuity in preparing double deck bunks have made this bare brick floored barracks room a fairly comfortable duration home. Tosh Ninomiya left, is charged with the responsibility of documenting the history of the Amache Center." (12/09/1942)]

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. Another peculiar thing about that Granada camp was this; that they brought in tools from surrounding C. C. C. camps and they have a building completely filled with wheelbarrows and shovels and hammers and axes and saws and tools of all kinds and descriptions -- carpenter's and other tools. They are mostly shovels and wheelbarrows, however.

They have a whole building completely filled with them, and yet they were not going to let a single one of those evacuees do one nickel's worth of work on this school building -- rough labor or skilled labor or any other kind of labor. At the same time they had at least a thousand idle men loafing around that colony with nothing to do and, as I understand Mr. Nicholson, perfectly willing to work.

Of course, on the 15th of January I will say that, owing to my protest down at the facility review board on this school-building proposition, the W. R. A. did work out some kind of compromise, so that some of these evacuees could work on that contract. However, up until that time it was absolutely prohibited, and they would not even let them dig a ditch to lay the cement. They would not let them touch a thing or have any part of it at all. They would not let them do any part of it. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Senator CHANDLER. Senator Murray.

Senator MURRAY. Would it have been practical to have sent some of these skilled and semiskilled Japs up to these places where the permanent relocation centers were being established to do that work and have them housed in temporary buildings, like fairgrounds, and so forth, and have them take part in the construction of their own permanent camps? Wouldn't that have been possible?

Mr. NICHOLSON. It wouldn't have been possible, but impractical, from this point of view: When the job was being rushed so rapidly, a certain amount of union labor had to be used.

Senator MURRAY. In the rushing of it you created tremendous dislocations in our own communities. For instance, up in eastern Montana we were drained of farm labor. They went down to this camp in Wyoming and they were paid enormous salaries to work down there, and it created such a resentment that it affected me in my campaign. I never heard such criticism and such denunciation of the administration for allowing that to occur down there in Wyoming. They paid enormous wages to men who could only drive a nail or use a saw. They classified them as carpenters, and they got these enormous salaries and wages.

I thought that you could have shipped out some of these Japs and housed them temporarily in fairgrounds or some places like that -- you would not have so many of them -- and they could have built those buildings themselves.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. Right up at Heart Mountain in Wyoming they are constructing school buildings, and the Japs are right there in the colony sitting around twiddling their thumbs. Right at Heart Mountain, Wyo., near Cody, the Japs are not working on the school buildings at all. They are private contractors, paying the same wages, bringing them in from other places, right at the hour when they have the Japs there.

Senator MURRAY. That seems to be terrible.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. It is outrageous.

Senator GURNEY. Well, the union probably won't allow them in.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. Well, they are in there. The Japs are there.

Senator GURNEY. But the unions won't let them work.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. They can construct the building without any union. They have men enough there to construct the whole building.

Senator GURNEY. I admit that, but the contract has been let, and the contractor has made his agreement with contract labor.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. That is right. That is what has happened.

Senator GURNEY. So you can hardly change it at the moment.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. No; but it is a reflection on the administration of the W. R. A. and a reflection on their management of the whole thing to enter into that kind of contract.

Senator GURNEY. I entirely agree with you.

Senator JOHNSON of Colorado. Because, as Mr. Nicholson has pointed out, one of the important things in handling one of these camps is to provide work for them.

Mr. NICHOLSON. The segregation is No. 1 and, I would say, work is No. 2 in importance.

Senator GURNEY. And the maintenance of complete personnel records? That would follow?

Mr. NICHOLSON. That is just part of the management; yes.

Senator GURNEY. Are you about through, Mr. Chairman?

Senator CHANDLER. If you are through, gentlemen, I am. Thank you for responding to the request of the committee and for giving us this valuable information concerning this problem, Mr. Nicholson.

(Thereupon, at 12:20 p. m., the subcommittee adjourned, subject to call of the chairman of the subcommittee.)

WAR RELOCATION CENTERS

THURSDAY, JANUARY 28, 1943

UNITED STATES SENATE,

SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON MILITARY AFFAIRS,

Washington, D. C.

SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON MILITARY AFFAIRS,

Washington, D. C.

The subcommittee met, pursuant to call, at 2:30 o'clock, Senator Albert B. Chandler presiding.

Senator CHANDLER. Gentlemen of the committee: We are greatly honored to have Ambassador Grew, our Ambassador to Japan, present.

The subject of this inquiry is the Japanese problem generally in this country, with particular reference to the relocation camps of Japanese who are presently interned, and if you have a statement, Mr. Ambassador, we will be glad to give you an opportunity to make it, and then the committee may want to ask you some questions. We are grateful to you for your presence here.

Mr. GREW. Mr. Chairman, I think I ought to say at the start, speaking purely for myself, that this is a general subject with which I am very little familiar, for this reason: Of course, from the moment of Pearl Harbor we were locked up in our Embassy in Tokyo and had no contact with the outside world at all. We were incommunicado in every respect, so that during our 6 months' internment I had no opportunity to know what was going on in the Japanese prison camps at all, knew nothing until we got on board the exchange ship. Then, of course, we compared notes with some of the people who had been released from prison camps in Hong Kong and in Japan. Of course some of our own civilian people had been held actually in prison during those 6 months, but we were not in contact with any of our prisoners of war. They were not released. So that up to the time of my arrival in the United States I knew practically nothing about the treatment of our people over there, except those who came back with us, who had been kept in prison. I knew a great deal about that, and when I came back I made a broadcast confirming newspaper stories which had been issued by the correspondents on board the ship.

Ever since I have returned to the United States I have been going around the country, mostly under the auspices of the Office of War Information, speaking everywhere, so that I have been very little in Washington and I have had practically no opportunity to keep up to date on the reports which have come in from the Swiss Minister to Tokyo and the International Red Cross, the channels through which we receive our information about conditions in those camps.

That, so far as I am concerned, is about the whole story, and that is why I requested Mr. Gufler to come up today, as he is Assistant Chief of the Special Division of the State Department which is in touch with all these matters and to which all these reports about conditions in the prison camps of Japan naturally flow. He has all the latest reports, and he would be in a position probably to answer any specific questions on the treatment meted out to our citizens over there, both prisoners of war and interned civilians.

That, to start, is all I can say.

Senator WALLGREN. Mr. Chairman, would it be all right for me to explain to the Ambassador what has taken place up to now so far as our Japanese are concerned on the west coast?

Senator CHANDLER. Yes.

Senator WALLGREN. At the outbreak of this war we had 120,000 Japanese in the three West Coast States of California, Washington, and Oregon. A great many of these people were residing around certain strategic areas, such as Terminal Island, in Los Angeles, around San Pedro, and around a great many of our airplane factories, power installations, and so on.

After several hearings held among the members of the delegations of the three West Coast States we made recommendations to the President that he create certain strategic areas in those three States and evacuate those areas, not to declare martial law but just sort of license these people to remain within the area, and then revoke the license of anyone he thought should not be in the area.

This finally evolved itself into a plan to create evacuation camps, and they were created in such places as Manzanar, Santa Anita race track, and places of that sort; so the Army started in immediately to evacuate these strategic areas by presidential proclamation. So these Japanese were all brought into these camps -- men, women, children, citizens, Japanese born in this country, and so on, were all brought into these camps, and under the direct supervision of the Army.

For a time this operated very nicely, and then the President, I presume, decided to place this all in the control of the War Relocation Board for the purpose of trying to relocate these people. That has been in operation now for several months, and during that period of time they have had in their entire population a great many Japanese who have been trying to incite the others and causing many disturbances. There has been no effort on their part to segregate them, to separate them. I presume they have made some effort to relocate some of these people, but the testimony up to now is to the effect that there are at least 2,000 of these Japanese who have been out on furloughs, you might say, that have not reported back to headquarters, and one of the things that I would like to know is whether or not you believe that we can take a chance in allowing these people a great deal of freedom under existing conditions.

It isn't my idea to persecute these people by any means. I would like to help them. But with this war going on and with all the bitterness that might be created because of the loss of sons and brothers and relatives over there in the South Pacific, it might not be any too safe to allow some of those people too much freedom, and it might be for their own protection to keep them under strict supervision and under some sort of protection on our part.

On the other hand, I contend that it might be advisable for the Army and for the F. B. I. agents, through any sort of system they may have, to determine a program of segregation, to try and take these men out of the camps that might be causing us trouble, and place them into a strict internment camp, and then in turn try and farm these other people out into spots where they might be able to help us out with our manpower problem.

That is about the size of it, although we would like to know just how our people are treated over in Japan, whether or not you feel that the Japanese that are in this country could be loyal to this country under any conditions.

Mr. GREW. Mr. Chairman: In the first place, Senator, are the 120,000 Japanese you speak of all Japanese subjects, or are some of them Nisei?

Senator WALLGREN. There are about 60,000 Nisei.

Mr. GREW. Frankly, this is a subject to which I have not had any opportunity to give careful thought. It is essentially a domestic problem, and I have been dealing almost exclusively since my return with problems connected with Japan direct.

I would say, Mr. Chairman, without any hesitation, that under war conditions we must allow nothing whatsoever to interfere with our war effort, to endanger the war effort or our security in any way. That is just plain common sense that goes without saying.

Taking that as a basic principle, the question arises whether it is not going to be possible to segregate the sheep from the goats. In other words, I believe myself that there are many thousands of so-called Nisei, American citizens of Japanese descent, whose loyalty can be depended upon 100 percent. I don't have the slightest doubt about it. I think probably a very small percentage could not be depended upon; and here you have this large element of Nisei who are actually American citizens. I conceive that they can be a healthy element in the country, and I should hate to see steps taken which would so alienate them that the measures taken by our Government would drive them into the other camp against their will. I think that is a possibility, and I think it is a matter which should be given consideration.

The whole thing seems to me to boil down more to a question of method than anything else, the method of segregating the sheep from the goats, the method of ascertaining who can be depended upon and who cannot. I don't know whether that is for the F. B. I. or what organization would undertake it, but I think a primary consideration should be that we must take no chances at all in allowing anybody who could conceivably interfere with our war effort, who could conceivably undertake espionage against us, to remain free. Having that in mind, I would like to see on the other side efforts made not to antagonize and alienate this very large proportion of the Nisei who are held in these camps.

That, I think, in a nutshell, represents my views on the subject.

Senator WALLGREN. Then segregation, of course, is the first thing that should be done.

Mr. GREW. Yes.

Now, Senator, I think you asked me something about the treatment of our people over in Japan.

The categories of our people in Japan fall into three classes. In the first place there are the prisoners of war; in the second place there are the interned aliens, civilians; and in the third place there are the Americans who were put in prison and held in prison during the 6 months between Pearl Harbor and our evacuation for the purpose of ascertaining whether or not they were American spies. The Japanese assumed that I had a network of spies all over Japan, just as, presumably, they have networks of spies all over the countries where they have embassies, and many of these people who used to come to see me, newspapermen, missionaries, businessmen, teachers, of course, used to come to the Embassy to find out what I could tell them about the situation and tell me what they could contribute, some of them very good friends of mine whom I often saw. Many of those people were picked up and put into solitary confinement because they were looked upon as potential spies, and the police wanted to find out what I had instructed them to report and what they had reported to me.

Many of those people, in the course of their interrogation by police, were certainly subjected to the third degree or worse, but finally when the police found that they were on the wrong track, when they were finally convinced there was no espionage going on, this treatment eased up at once. They were given better food, allowed food to be brought in from the outside, allowed books, and all the rest of it.

That deals with that category of people who were in prison.

Senator WALLGREN. Were they allowed any freedom at all?

Mr. GREW. They were kept in prison until the end of their examination, and in certain cases where the examination was completed before the end of the 6 months they were turned into the internment camps.

Senator WALLGREN. Can you describe those camps to us?

Mr. GREW. I can tell you of reports we have received through the Swiss Minister, because the Swiss Minister and the International Red Cross frequently visit these camps and report on them. They have not been able to visit the camps in the Philippines, in Formosa or Singapore, for example, but they have visited camps in Japan.

I have here before me a résumé of the reports which have come in to us, and it is a question of whether you care to have me read this.

Senator O'MAHONEY. Mr. Chairman, before the Ambassador reads this statement may I ask him to discuss with us, if he will, the situation in Japan with respect to the diverse ideologies that exist there, if any? In other words, what sort of a liberal or democratic sentiment is there to be found among the Japanese nationals themselves, and to what degree is the Japanese Government policy a policy of force that is imposed upon people who might, if permitted, adopt a more liberal attitude?

Mr. GREW. Is the Senator referring to post-war Japan?

Senator O'MAHONEY. No, the conditions as you found them when you were in Japan.

Mr. GREW. Mr. Chairman, that is a question that I think involves both fact and opinion. I will be glad to deal with both if the Senator wishes. In the first place, the fundamental ideology in Japan is Shintoism, which is essentially ancestor worship. That goes all through the ranks, all through all classes in Japan. They all regard the Emperor as a demigod. He is supposed to be descended from the Sun Goddess, who is originally alleged to have created Japan. His family line is supposed to have come down unbroken for 2,600 years, which I think would be pretty difficult to prove on paper, but all of the people of Japan look at him in that light.

That Shintoism is essentially a patriotic cult. Apart from that they have their religions. There is the Buddhist religion, a Buddhist sect, and Christianity, which, up to the outbreak of the war, was completely tolerated. The only thing they did before the war was to insist on the transfer of authority, we will say, in the Christian Church, from many of our foreign missionaries to Japanese, Japanese bishops, and other clergy. Roughly there are, I would say, 300,000 Christians in Japan today, and I do not know to what extent the authorities, the police, are going to try to stamp Christianity out. I cannot tell; I don't know. My guess is that they will not try to stamp it out, because I don't believe they will dare do it, because I think they will probably realize they cannot do it.

They may perhaps insist that the Christians' churches over there include Shinto shrines, which the Christians may have to accept on the ground that that is purely a patriotic cult; but even if the police drive them underground, take over their churches, I myself believe Christianity will continue to exist. It is very firmly and deeply rooted. I don't believe you can drive it out of Japan. That is roughly the situation with regard to the ideologies and religions there.

I think the Senator also raised the question as to how much chance there is of some liberal element coming up and registering itself. This is the idea -- something democratic?

I would say this: Of course, in war Japan is absolutely totalitarian. Every Japanese must and will support the Government to the limit. He must do it -- or else! A mere word of criticism of the Government would bring the so-called thought-control police [Kenpeitai] down on him at once. He couldn't do it.

Every Japanese, whether he wants to or not, will be obliged to fight to the last ditch. Taking that as something fundamental, I not only believe but I know that there are many elements in Japan who did not want the war, who did everything in their power to prevent the war but were, of course, powerless because the military machine went over them, but elements which I believe in the future can be used as foundations on which to build something healthy once we have completely cut out the cancer of militarism from Japan in the Far East.

We can only do that by first completely defeating their military machine, and that means the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force, on the field of battle, by air, land, and sea, so that they are not only impotent to fight further but so that they become discredited in the eyes of their own people, and so that they cannot reproduce themselves in the future. Anything else would be utterly stupid.

For instance, if they should offer us some kind of peace proposal, that they would withdraw from some or all of the areas they have taken and sit down and have an armistice, what they would do would be to consolidate their forces and begin to build up their military machine again, and some day we would have that all on our hands again.

I do not believe Japan can ever become a democracy. They are not built that way. I don't believe it would be sensible in the future ever to try to foist on Japan an entirely different kind of government.

(Further discussion at this point was off the record.)

Senator O'MAHONEY. Would it be a justifiable conclusion to say that there are substantial elements in Japan which, if they were not controlled by the military machine, would be amenable to our ideas of social existence and political control?

Mr. GREW. Without any shadow of doubt, Senator, I would say so.

Senator O'MAHONEY. So that there is nothing inherent in the Japanese nationality which would lead anybody to conclude that those American citizens of Japanese ancestry who are now in these various war relocation camps cannot be trusted, generally speaking?

Mr. GREW. There is nothing that justifies those conclusions.

Senator O'MAHONEY. In other words, we ought to follow the policy not of condemning all of these Japs, but of seeking to find out those who cannot be trusted.

Mr. GREW. I feel so very strongly.

If I may, if I am not taking up your time, I might give you a little illustration to try to prove my point about this.

The average Japanese, and I have known him pretty intimately all these 10 years, is normally a pretty gentle, friendly, quiet, beauty-loving and peace-loving person -- the average Japanese -- not all of them, but we will say a cross-section. I have known servants in our house, the tradespeople, the gardeners, and all classes of people right up to the top. That is their natural character, until they get into the military machine, and that is where they are brutalized and taught brutality.

You just take a cross-section of the Japanese, the man in the street, we will say. During the war the Japanese police used to arrange demonstrations against our embassies. They would herd hundreds of Japanese whom they would pick up in various quarters and drive them down to the embassies to demonstrate. They would come first to the British Embassy and then to us. On the day of the fall of Singapore they had hundreds of these Japanese first at the British Embassy and then they came down the street in front of our Embassy. They came right up against the bars behind which we were imprisoned, with pennants across their breasts, Down with the United States, shaking their fists at us and shouting, and the police around the edges driving them on.

One of my staff happened to be standing on the balcony of our office overlooking this mass. For some unknown reason he took out his handkerchief and waved it at this crowd and laughed, and they stopped howling, and then they took out their handkerchiefs and waved back and they laughed, and the police went from group to group trying to stop this laughter, and they couldn't do it, and finally this whole gang of hundreds of Japanese went away up the street, laughing.

That is no indication of any fundamental hatred of the Americans on the part of the Japanese. I merely submit that incident to perhaps bolster up the theory I mentioned.

Senator WALLGREN. How about these followers of Shintoism that are here in this country? Could we expect loyalty from them?

Mr. GREW. Shintoism is not necessarily a cult which would interfere with our Government or country or Christianity. It is the old worship of their own ancestors. A perfectly loyal American-Japanese might have his little Shinto shrine in the house, might bow before it and burn incense before it every day, which is as much as to say he wants to keep in touch with the members of his family who have gone before.

"Japanese Shinto temple ceremonies, at San Jose, lure devout Buddhists

from miles around. More than 2000 attended the rites, which ended with the traditional 'Odori' dance by Japanese maidens, two hundred Japanese children, picturesque garbed in the costumes of their ancestral land paraded in the two-day Buddhist celebration." (1935-10-22)

Senator WALLGREN. Could you elaborate a little bit on the treatment of these people that are in these alien camps that you speak of, after they have been released from prison, after the Japanese found out they were not spies?

Mr. GREW. Mr. Chairman, do you wish to have me read this statement?

Senator CHANDLER. Yes, if you would like.

Mr. GREW. It is entitled "Treatment of Americans held by Japanese authorities as Civilian Internees and Prisoners of War."

The United States and Japanese Governments have agreed reciprocally to apply the provisions of the Geneva Prisoners of War Convention to prisoners of war held by them, and to apply the same provisions to civilian internees in so far as the provisions are adaptable to civilians.That, Mr. Chairman, is roughly a résumé of the information which so far has come in to us from the Swiss Minister in Tokyo and his staff and the International Red Cross.

The American Government applies the provisions of the Geneva Convention to the Japanese prisoners of war and to the approximately 3,000 Japanese civilians interned in the United States in the hands of the Departments of War and Justice. It has not, however, undertaken to apply the Convention to the 110,000 Japanese nationals, and American citizens of Japanese ancestry in the 10 centers operated by the War Relocation Authority.

The persons in the relocation centers, two-thirds of whom are American citizens, were not placed in the centers because they were individually suspect or because anything was known to indicate that they were dangerous as individuals. Japanese nationals who were suspect as individuals have been placed in regular internment camps.

American citizens are held in at least 35 places in Japan and Japanese-controlled territory. These places of detention are located from Fushun, Manchuria, to Java, and from Zentsuji, Japan, to Hankow. The number of persons detained in one place varies from one to several thousand. Civilians are usually held in relatively small groups and prisoners of war in larger ones.

Representatives of the Swiss Government, which is charged with the representation of American interests in Japan and Japanese-controlled territory, and representatives of the International Red Cross Committee, have been permitted to visit camps in Japan, Korea, Manchuria, and China. They have not been permitted to visit camps in Formosa, Java, and the Straits Settlements or the Philippines. The Swiss Minister in Tokyo is pressing for permission for his representative to visit these outlying areas, but it is impossible to state when his efforts are likely to be successful.

The treatment of Americans in Japanese hands varies greatly, depending on the area in which they are held, the Japanese authority having jurisdiction over them, and the personality and background of the individual camp commander. In the more settled regions at a distance from zones of war treatment is usually better than in more recently conquered regions. Camp commandants who have had previous experience with western peoples or have been in Europe or America usually are much more liberal in their treatment of Americans than are those who have had no previous occidental contacts.

The buildings where Americans are being held vary from new buildings, built for the purpose on the former race track at Shanghai, to port area shelters, originally built for Japanese workmen. Although many of the civilians held in Japan have western-style beds, the prisoners of war usually are supplied with Japanese sleeping mats. Bathing facilities are generally provided, but they are sometimes inadequate or the prisoners are not supplied with as much fuel as they desire. Clothing has been supplied in some cases from captured British stores and in some cases from Japanese army stores.

The diet of the internees and prisoners is built almost entirely upon foods which may be obtained in the Far East. It is probable that sufficient supplies of western-type foods do not exist in the Far East to make western diets possible.

That I know to be a fact. I talked to the Swiss Minister before we left, and he brought pressure to bear on the Japanese authorities to see that they did get western food, in the shape of meat, vegetables, eggs, milk, and that sort of thing, but some of those things were practically nonexistent there.

Before we left Tokyo -- I think it was after Pearl Harbor, but I heard definite reports of it -- the guests in the hotels in Tokyo used to line up in queues about an hour before meals in the hope that they would get at the dining room before the meals gave out. They generally didn't have enough food to carry on. The Japanese were very short of the sort of food you would serve in hotels, so the fact that our prisoners of war don't get many of the kinds and classes of food they are accustomed to in many cases depends on the fact that the Japanese just don't have those classes of food.

The Swiss Legation in Tokyo reports that prisoners of war in four camps which its representatives have visited recently enjoy a larger ration than that given Japanese reservists. For instance, Japanese soldiers are given 570 grams of rice and barley each day while the American prisoners are given 650 grams. Fats and meats are distributed in extremely small quantities; but 700 grams of fish are issued per week for each prisoner. Other protein foods are also provided, often beans in some form. The diet provided by the Japanese authorities is being supplemented by Red Cross parcels and camps in Japan received gifts of tinned foods and fats at Christmas time from the members of the Tokyo diplomatic corps.

In accordance with the provisions of the Geneva Convention enlisted men who are now prisoners of war are being required to work. It is known that some are unloading ships in Japanese ports and others are doing agricultural work. The remuneration which the prisoners receive for this work is extremely small, but efforts are being made to reach an agreement with the Japanese Government in order to increase the wage level.

Medical facilities have not been satisfactory in most cases on account of shortages of needed medicines and primitive nature of Japanese hospitals, though the Japanese have apparently been making efforts to provide more adequate medical treatment.

Recreational and religious opportunities vary greatly. At some camps books and recreational supplies are available; at others they are scarce or almost entirely lacking. At some camps the commandants permit full religious activities and at others they view the exercise of occidental religions with suspicion and place restrictions upon them. The Swiss and Red Cross representatives are making efforts that have already met with some success to improve these conditions.

The morale of Americans interned or held as prisoners of war in Japan is reported to be extremely good. This is in spite of lack of news from their families in the United States, lack of recreational facilities of the kind to which they have become accustomed, lack of medicines, restricted practice of the forms of religious worship, and the difficult conditions of housing and food mentioned above.

Senator WALLGREN. How many United States citizens were in Japan at the outbreak of the war?

Mr. GREW. I think there were something like 4,000, but I am not sure, off-hand. I can't give you the exact figures.

Senator LODGE. What is the date of that?

Mr. GREW. This has just been written today, compiled from the various reports and telegrams that we have received in the last several weeks past -- a compilation.

Senator CHANDLER. Mr. Ambassador, testimony heretofore given before the committee indicates that in the War Relocation Centers they are undertaking to permit the Japanese a sort of self-government, a sort of government that they make themselves. Would you give us some advice about what you think of that, and how successful that would be, with the understanding, of course, that there are Nisei and Issei and Kibei all there together?

Mr. GREW. I think, Mr. Chairman, it would depend very much on the practical results obtained. As I say, I don't know very much about this problem myself, because I haven't been in touch with it, but I understand that in most of the camps the actual camp government has functioned fairly effectively. I was told, and I believe it is true, that on one

occasion

when a few troublemakers appeared -- and, mind

you, I think the element of troublemakers is a very small proportion of

the whole -- a group of Japanese Boy Scouts came in,

raised

the American flag on the central flag pole, and some of these

roughnecks, these troublemakers, apparently were threatening to go

up

and pull down the flag, and these little Nisei Boy Scouts formed a

guard around the flag to protect it, on their own initiative. [PHOTO:

"Amache Summer Carnival Parade." (Granada, 07/10/1943)]

occasion

when a few troublemakers appeared -- and, mind

you, I think the element of troublemakers is a very small proportion of

the whole -- a group of Japanese Boy Scouts came in,

raised

the American flag on the central flag pole, and some of these

roughnecks, these troublemakers, apparently were threatening to go

up

and pull down the flag, and these little Nisei Boy Scouts formed a

guard around the flag to protect it, on their own initiative. [PHOTO:

"Amache Summer Carnival Parade." (Granada, 07/10/1943)]Senator WALLGREN. Where was that?

Mr. GREW. That was in one of our relocation camps. It is just a little incident, but I think it may be significant.

Senator CHANDLER. We have had some testimony heretofore given to the committee that they would get along better if the officials of the Government made rules for them to follow, instead of permitting them local self-government within the camps.

Mr. GREW. To have the camp run by officials of our Government?

Senator CHANDLER. Yes; to have them make the rules and just indicate to the Japanese what the rules were.

Mr. GREW. Well, Senator, frankly, I have no experience myself to justify an opinion, but I would say offhand that in most walks of life you get better results by having the people who are concerned carry on their own business, so to speak. That is just general. I can't say -- I really don't know enough about the problem here to advise on it.

Senator JOHNSON. The Ambassador mentioned a moment ago that he did not think that the Japanese would respond to democracy in Japan. I wonder, isn't that the same problem?

Mr. GREW. Well, we are talking now largely about Nisei, about American citizens of Japanese origin, many of whom, and I would say the larger proportion of whom, are thoroughly loyal American citizens, who have grown up here and never known Japan and don't speak Japanese. Their whole outlook, their whole life, is surrounded by American traditions. Those people have been brought up in American democracy, and will function in the democratic method; but I think it would be very hard to graft democracy on the Japanese Nation as it exists over there. It is quite a different problem.

Senator WALLGREN. Have you any opinions on this question of dual citizenship that you would care to express?

Mr. GREW. That is an exceedingly complicated problem, Senator. It is a very complicated problem.

Senator WALLGREN. How is it viewed in Japan?

Mr. GREW. I have taken occasion to get together the actual facts on that subject, and they are very complicated indeed. The Japanese have various interpretations of their laws on that subject. Here is the story, right here, if you wish to see it.

Senator WALLGREN. Would you read it?

(Discussion at this point was off the record.)

Mr. GREW (reading):

That is a little complicated, but all the facts, I think, are there.

A Japanese domiciled in the United States but born in Japan is referred to in Japanese as an Issei (first generation); a Japanese born in the United States of parents born in Japan is referred to as a Nisei (second generation); and a Japanese born and resident in the United States but educated in Japan is referred to as a Kibei (returned to America).

The pertinent portions of Japanese law governing nationality in cases of persons born in the United States to Japanese parents are quoted below:

Japanese Law No. 66 of March 1899. As revised by Law No. 27 of March 1916, and by Law No. 19 of July 1924, effective December 1, 1924.

ARTICLE 1. A child is regarded as a Japanese if its father is at the time of its birth a Japanese. The same applies if the father who died before the child's birth was at the time of his death a Japanese.

ARTICLE 20. A person who acquires foreign nationality voluntarily loses Japanese nationality.

ARTICLE 20 (2). A Japanese who, by reason of having been born in a foreign country designated by Imperial Ordinance, has acquired the nationality of that country, and who does not as laid down by order express his intention of retaining Japanese nationality, loses his Japanese nationality retroactively from his birth.

"Proud Mrs. Kumiko Noda, 23, evacuee from Florin, California,

holds her new son, Newell Kazuo Noda. Baby Newell arrived at 6:12 A.M., Sunday, June 12, and was the first child born at this War Relocation Authority center for evacuees of Japanese descent." (Tule Lake, 07/01/1942)

Persons who have retained Japanese nationality in accordance with the provisions of the preceding paragraph, or Japanese subjects who, by reason of having been born in a designated foreign country before its designation in accordance with the provisions of the preceding paragraph, have acquired the nationality of that country, may, when they are in possession of the nationality of the country concerned and in possession of a domicile in that country, renounce Japanese nationality if they desire to do so.

Persons who shall have renounced their nationality in accordance with the provisions of the preceding paragraph lose Japanese nationality.

ARTICLE 24. Notwithstanding the provisions of Article 19, article 20, and the preceding three articles, a male of full 17 years of age or upward does not lose Japanese nationality, unless he has completed active service in the Army or Navy, or unless he is under no obligation to serve.

A person who actually occupies an official post, civil or military, does not lose Japanese nationality notwithstanding the provisions of the preceding eight articles until after he or she has lost such official post.

ARTICLE 26. If a person who has lost Japanese nationality in accordance with the provisions of article 20 to article 21, inclusive, is domiciled in Japan, he or she may, with the permission of the Minister of the Interior, recover Japanese nationality. But this rule does not apply to cases in which the persons mentioned in article 16 have lost Japanese nationality.

It is understood that the expression of intention of retaining Japanese nationality, provided for in article 20 (2) must be made by the parent within 2 weeks after the birth of the child if the child is to retain the Japanese nationality acquired at birth under article 1. In this connection reference may be made to the provisions of article 2 of the Japanese regulations (Ordinance No. 26) of November 17, 1942, the first paragraph of which reads as follows:

"ARTICLE 2. Those desiring to preserve their nationality in accordance with the provisions of clause 1 of article 20 (2) of the Nationality Law, and being those who are required to submit a report of birth by clause 1 or clause 2 of article 72 of the Census Domicile Law, shall file a report to that effect, together with a report of birth, within the period set forth in article 69 of the Census Domicile Law."The period for the registration by the parent of the birth of a child, provided in article 69 of the Census Domicile Law, is 14 days.

From the foregoing provisions it would appear that a person of Japanese parentage born in the United States is regarded as a Japanese subject only if he has been declared a Japanese subject by his parents within 14 days of his birth.

While it may appear that the provisions of article 24 would preclude any Japanese male from divesting himself of Japanese nationality unless he has completed military service or has no obligation to serve, and while this provision is expressly applicable to article 20, the Department has been informed that it is not applicable to article 20 (2), which is regarded as a separate article.

Senator WALLGREN. Then there are a great many people of Japanese ancestry in this country who are not in any way citizens of Japan.

Mr. GREW. Many thousands of them.

Senator WALLGREN. And they are not permitted dual citizenship.

Mr. GREW. They are not permitted dual citizenship, and I think they are perfectly loyal American citizens.

Senator CHANDLER. If they were suddenly deprived of this citizenship they would have nothing.

Mr. GREW. They would have nothing at all. They would be outcasts.

Senator CHANDLER. And they would know that.

Do you want to ask any questions, Senator?

Senator O'MAHONEY. No.

Senator CHANDLER. Senator Johnson?

Senator JOHNSON. No.

Senator CHANDLER. Senator Gurney?

Senator GURNEY. Mr. Ambassador, I would like to gain the benefit of your experience over in Japan as much as we can for this committee, and I am hopeful that the committee will decide to give you a transcript of the hearings that we have had heretofore, in the hope that you can find time to go over them, or maybe have some of your acquaintances or staff go over them, and then give us the benefit of any suggestions you may have.

Mr. GREW. I will be very glad to do it, Senator. I am being sent south by the Office of War Information for a month, to speak all through the South, and before that time I am going up to New Jersey for a public address, so that I am only going to have about a day or at the most 2 days to touch base here before I go off on this trip. That is something that I take it is an urgent matter, isn't it?

Senator GURNEY. Yes; although you might put it in your grip with you on the trip. It might make good reading. Some of it would be interesting. You could hurry through it, if the committee feels they would like to have you do that. Personally, I would like to have the benefit of your advice on any matter, any Japanese matter, here, on which you feel you could be helpful.

(Discussion at this point was off the record.)

Mr. GREW. If I may, Mr. Chairman, I think I can say now in advance, in general, how I size up this whole situation.

In the first place, as I said in the beginning, we have got to take every essential step in order to protect ourselves from any disloyal Japanese, whether they are outright spies, whether they are trouble makers, whatever they may be. That goes without saying. In war we cannot take any chances. But, having that in mind as an a priori principle, I think we should make every effort not to alienate the many thousands of good, loyal, Nisei American citizens of Japanese origin just because they were born of Japanese blood. I believe that the very vast majority are loyal American citizens who would fight for us, who would be glad to fight for us. They have been reared in our democracy, they have had no contact with Japan; they haven't their families in Japan, they have their families here; their whole outlook is American.

Now, why not make use of those loyal elements? Why do anything that is going to alienate them? I say that without hesitation. So in my opinion this whole problem comes down, as I think I also said in the beginning, to separating the sheep from the goats.

Senator WALLGREN. There is one other point, that we must look to the protection of those people, too, and I think you feel as I do that the abolishment of those camps would be possibly the best thing we could do, after farming out the people.

Mr. GREW. I think probably so; as soon as we are satisfied that those people who are going to be let out are loyal American citizens.

Senator WALLGREN. My idea in introducing this bill in the first place was to bring this to a head. We felt that under the Army we had a better chance -- or I felt -- of getting proper discipline and a proper segregation than we have under the existing set-up. The quicker we can find out who is loyal and who may not be loyal, and the quicker we can get the loyal people out of those camps, the better off we will be, rather than to have them mingling with people who are always pointing out the fact, "Here you are, an American citizen, yet you are behind barbed wire."

"Evacuees enjoying games under the shade of trees near the creek which flows through the desert on the border of this War Relocation Authority center. (Manzanar, 07/03/1942)

Mr. GREW. Couldn't that segregation be made still leaving the Authority where it is?

Senator WALLGREN. They have had the opportunity for several months and haven't done anything about it. In the meantime they have allowed many of them to go out on furloughs and there are 2,000 that haven't reported back. They have granted these furloughs. We know they have had trouble in many of these camps, and I do know that there are many Japanese who themselves feel that there ought to be a segregation immediately, because they themselves do not like the idea.

Mr. GREW. That seems to be a question of method more than principle.

Senator WALLGREN. That is right.