RELOCATION PROBLEMS AND POLICIES

An address delivered by Dillon S. Myer of the War Relocation Authority before the Tuesday Evening Club at Pasadena, California, March 14, 1944.

Two years ago next Saturday -- on the 18th day of March, 1942 -- the War Relocation Authority was created by an executive order of the President of the United States. This new agency was confronted with a problem of unusual complexity in a field of human relations where misconceptions, confusion, and emotions stirred by the impact of the war were destined to produce wide and vigorous discussion. Many facts essential to a competent understanding of the problem have been obscured by misrepresentation and insufficient public information. I want to review some of them for you, in order to define the background of the policies which have guided the development of the WRA program during the two years since it came into existence.

The evacuation of 112,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast in the spring of 1942 was an undertaking without parallel in our national history. On February 19, the President issued an executive order authorizing the Secretary of War, or military commanders designated by him, to prescribe military areas from which any or all persons might be excluded, or in which their movements might be restricted. Though the order made no specific mention of any group that might be evacuated, it was immediately and correctly interpreted as a forerunner to the exclusion orders that were issued by the military a few weeks later. As a result, many people of Japanese descent began to move voluntarily away from the West Coast area. This movement was accelerated on March 2 by a proclamation of the Commanding General of the Western Defense Command, designating two military zones in the states of Oregon, Washington, California, and Arizona from which certain persons might be excluded. Altogether, about 8,000 individuals of Japanese descent left the designated areas voluntarily and tried to establish new homes on their own initiative.

I want to emphasize that neither the President, in his orders authorizing the designation of exclusion areas and creating the War Relocation Authority, nor the Commanding General of the Western Defense Command in any military proclamation, ever ordered or suggested that the people to be evacuated should be confined or restricted in their movements outside the exclusion areas on the Pacific Coast. It was soon apparent, however, that 110,000 people could not be ordered to leave the coastal area and migrate inland without some kind of assistance and supervision. In various communities eastward from the exclusion areas, the appearance of voluntary evacuees caused unfriendly tension and misunderstanding. Many families needed assistance in finding and traveling to new locations where they could support themselves and establish new homes.

These conditions became so acute that, on March 29, the Commanding General of the Western Defense Command issued a proclamation prohibiting further voluntary relocation. Thereafter, the evacuation was accomplished under Army orders, according to a definite schedule. The people were moved, first, into 15 temporary assembly centers where they remained under Army supervision until the relocation centers, operated by the War Relocation Authority, were ready to receive them.

These WRA centers were intended only as way-stations where the evacuees could reside while arrangements were made for them to relocate in normal communities outside the exclusion zones. About two-thirds of the evacuees were American citizens by birth, as you probably are aware.

The responsibility of the War

Relocation Authority for the evacuees

began with their arrival at the relocation centers. Ten centers were

built to receive them. These centers, constructed by the Army, are

large cantonments of barrack-type buildings, usually covered with tar

paper and lined with wallboard. Each building used to house the

evacuees is 100 feet long and 20 feet wide, and originally divided into

four, five, or six one-room apartments, allowing about 100 square

feet of floor space for each person. The standard equipment for

each apartment included a heating stove and a broom, plus a cot,

mattress, and two Army blankets for each individual. All other

furniture and equipment had to be supplied by the evacuees themselves.

[PHOTO: "A typical interior of a barracks home." (Jerome, 11/17/1942)]

The responsibility of the War

Relocation Authority for the evacuees

began with their arrival at the relocation centers. Ten centers were

built to receive them. These centers, constructed by the Army, are

large cantonments of barrack-type buildings, usually covered with tar

paper and lined with wallboard. Each building used to house the

evacuees is 100 feet long and 20 feet wide, and originally divided into

four, five, or six one-room apartments, allowing about 100 square

feet of floor space for each person. The standard equipment for

each apartment included a heating stove and a broom, plus a cot,

mattress, and two Army blankets for each individual. All other

furniture and equipment had to be supplied by the evacuees themselves.

[PHOTO: "A typical interior of a barracks home." (Jerome, 11/17/1942)]There is no plumbing in the buildings where the people reside. The wash rooms, latrines, and laundry rooms are housed separately, each unit serving about 250 people living in 12 barracks. Meals are served in mess halls, cafeteria style.

Since March, 1943, the War Relocation Authority has been registered with the Office of Price Administration as an "institutional user" of foods, and has abided by all OPA restrictions on institutional consumers. In fact, WRA was adhering voluntarily to the quotas suggested by OPA even before rationing became mandatory. Every center observes two meatless days each week.

The maximum food cost permitted in a center is 45 cents per person per day or 15 cents per meal. This food is purchased through the Army Quartermaster Corps, or grown on the farmlands that surround the centers. Evacuee farm crews grow and harvest a considerable part of the vegetables served in the mess halls, and nearly all the centers also produce poultry, eggs, and pork. A few produce beef and dairy products. [PHOTO: "Harvesting spinach." (Tule Lake, 09/08/1942)]

In addition to supplying the evacuees with housing and food, the War Relocation Authority provides two other services: medical care and schooling for the children through high school. The medical program is operated largely by evacuee doctors, and the school curriculum is planned to stress Americanization activities.

The first nine months after the creation of the WRA, on March 18, 1942, were chiefly devoted to the difficult job of establishing the necessities of community life in the ten new wartime cities. Transfer of the evacuees from the assembly centers to the relocation centers continued from early May until November of 1942, and the WRA staff had its hands full getting them housed, arranging to feed them, providing sanitation and safeguarding against the outbreak of epidemics, establishing police and fire protection, and attending to numerous urgent details. Every day we faced new emergencies.

Even then, however, in the midst of the transfer operations, we started a seasonal leave program, permitting workers to depart from the centers as a means of relieving the manpower shortage in western agricultural areas. In 1942 nearly 10,000 evacuee workers were given leaves from the centers to participate in harvest operations. Last year an approximately equal number left the centers on seasonal leave.

In connection with this seasonal work, I want to read an extract from a letter, written by the President of the Chamber of Commerce in Twin Falls, Idaho, describing the service the evacuees gave to this one community. He wrote:

"The citizens of the Hunt Relocation Center have performed a most patriotic service to the farmers of southern Idaho to the war effort, since their evacuation here less than fifteen months ago. Approximately 2,500 Japanese Americans have helped to harvest our bumper crops the past two falls, and helped to cultivate them the past summer. Without their help thousands of acres and tens of thousands of tons of foodstuffs would have rotted in the field each year." [See TIME Magazine, Crisis in Beets.]

Meanwhile we began in the late summer of 1942 to gear up a program for relocating the evacuees in year-round employment and in normal communities outside the evacuated area. One problem that had to be given major consideration in our planning from the start was the necessity of taking adequate precautions to safeguard the national security. Despite the rumors you may have heard and the changes that have been made, we have recognized all along that some of the evacuees have stronger ties with Japan than with the United States.

But in the beginning we had no records by which we could identify those strongly pro-Japanese individuals. We knew that immediately after the declaration of war against Japan, on December 7, 1941, and before the War Relocation Authority came into existence, the Federal Bureau of Investigation had acted to apprehend all aliens believed to be potentially dangerous to the national security. We knew that these individuals had been sent to internment camps and were not part of the population received at relocation centers. Nevertheless, we started almost immediately building up records on the relocation center population.

The most important step in this process was taken in February, 1943. In collaboration with the Army, the War Relocation Authority conducted a mass registration of all persons in the centers above 17 years of age. Both men and women, citizens and aliens, were required to fill out questionnaires calling for information on such matters as education, previous employment, relatives in Japan, knowledge of the Japanese language, investments in Japan, organizational and religious affiliations, and other pertinent matters. In addition, the citizen evacuees were asked to pledge allegiance to the United States, and the aliens were asked to promise that they would abide by the Nation's laws and not interfere with the war effort. The information obtained from these questionnaires has been extremely useful in identifying strongly pro-Japanese or potentially dangerous individuals who are denied the privilege of leave under our regulations. In addition, we have gathered extensive information from other sources pertaining to the backgrounds and attitudes of the individual evacuees. In many cases information has been sought from former employers, former neighbors, municipal officials, and others in the communities where the evacuees lived before the evacuation. We have consulted the files of federal intelligence agencies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation, for any information available there on the people in the centers whose eligibility for leave was receiving our attention. We have made full use of our own records at the centers, including internal security and employment records, to obtain information regarding the conduct of individual evacuees since they came under the supervision of the War Relocation Authority. Many of our dockets of information on individual evacuees run to ten and twenty pages and all this information is considered in determining the eligibility of evacuees for indefinite leave. Within the past several months we have taken steps to segregate those who are ineligible for leave from the bulk of the evacuee population, and we have quartered such individuals at the Tule Lake Center.

I want to say just a few words here about the population at Tule Lake. Most of the adult people detained there have indicated either by word or by action that they prefer to consider themselves Japanese rather than American. There are, among them, a considerable number of agitators and trouble-makers who have revealed definite inclinations to hinder the American war effort and to interfere with the orderly administration of the center. On the other hand, another and much larger element in composed of elderly aliens who have simply given up the struggle to adjust themselves to circumstances brought on by the war, and who want nothing more than to live out the rest of their days in the land of their birth. Still another group, larger than either of the previous two, is composed of children and young people whose records contain no evidence of disloyalty but who are living at Tule Lake simply because of family ties.

Several months ago, as I'm sure you'll recall, a group of trouble-makers at the center precipitated disorders which culminated in the calling in of the Army, by the Project Director, to administer the center until order could be restored. The trouble was the outgrowth of a strike, incited by agitators, which brought about a complete stoppage of work in harvesting vegetables grown on farmlands connected with the center.

The impression has been widely created in this State and in outer sections of the country that the summoning of troops into the Tule Lake Center indicated a complete and permanent breakdown of the WRA administration. I want to emphasize that we have always had a division of labor with the Army at WRA centers. Under the terms of our agreement with the War Department, we are responsible for all phases of internal administration at the centers, while the Army provides external guarding and checks the passes of people moving in and out. However, the agreement also provides that whenever violence is imminent and a show of force is needed, we can call in the troops stationed immediately outside the center for the purpose of restoring order.

Now that the segregation process is virtually completed, we are redoubling our efforts to restore the people living at the other nine centers to private life at the earliest opportunity. Those who oppose this program and advocate keeping all evacuees confined for the duration of the war are overlooking some rather fundamental provisions of the American constitution.

Virtually all legal authorities who have studied the matter, including the Attorney General of the United States, have expressed grave doubt that the Federal Constitution could be interpreted to permit a mass detention program in which American citizens were involved. The Supreme Court has never ruled on the issue, but a significant statement was made by Mr. Justice Murphy in connection with the Hirabayashi case wherein the Court upheld the validity of the curfew orders applied by the West Coast military authorities prior to the evacuation. In his concurring opinion, Mr. Justice Murphy said, "This (meaning the curfew) goes to the very brink of constitutional power."

Last July, the District Court of Northern California gave a decision which related more closely to the issue. Miss Mitsuye Endo, a resident of the Tule Lake Center (before it became a segregation center) had applied for a writ of habeas corpus to gain her release. This application was denied by the court solely on the grounds that WRA has a relocation program under which she could have applied for leave without calling on the court.

We now have in nine centers, excluding Tule Lake, about 70,000 men, women, and children who are eligible for relocation in normal communities, and approximately 19,000 others have already been relocated in communities scattered across the country from the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the Atlantic Coast. I have outlined the investigation that we make of each adult evacuee before granting leave clearance, and now I want to mention briefly another important procedure in our program. In connection with relocation, we have made it a practice all along to check community sentiment in areas where the evacuees are relocating. There has never been any serious question about relocating them in the larger cities, such as Chicago, New York, and Cleveland. But in smaller cities and towns we seek reasonable assurance from responsible public officials or citizens that the evacuees will be accepted. Before granting indefinite leave permits, we also make sure that evacuees have some means of support, and we require that they keep us informed of any change of address.

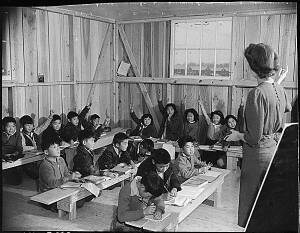

Our

biggest problem today is to find ways and means of

relocating thousands of families which include children and young

people whose alien parents desire to remain in America. There are

nearly 22,000 children under 19 years of age among the 74,000

people now living in the centers, not including Tule Lake. Those 22,000

children were born in this country. Those who are old enough to go to

school have gone to American schools, and they are still going to

American schools, where they have been taught the principles of

liberty, justice, and equality for which our country stands. [PHOTO:

"One of the third grade classes taught by Miss Rita Hayes." (Rohwer,

11/22/1942)]

Our

biggest problem today is to find ways and means of

relocating thousands of families which include children and young

people whose alien parents desire to remain in America. There are

nearly 22,000 children under 19 years of age among the 74,000

people now living in the centers, not including Tule Lake. Those 22,000

children were born in this country. Those who are old enough to go to

school have gone to American schools, and they are still going to

American schools, where they have been taught the principles of

liberty, justice, and equality for which our country stands. [PHOTO:

"One of the third grade classes taught by Miss Rita Hayes." (Rohwer,

11/22/1942)]The War Relocation Authority is firmly committed to the principle that American children should not be penalized for accidents of ancestry. The people of America, loyal to the traditions that have made our country great, will never agree that the solution of the problem is to deport these children to a strange land that many of them have never known. They will never agree that the solution is to keep them confined behind barbed wire fences.

Our job is to get them away from the relocation centers, into normal communities where they can develop into normal men and women. This relocation process cannot be accomplished, however, until we have opened the door for their parents to regain the means of self-support that they lost when they were evacuated. There are many fathers and mothers among them who speak the English language with difficulty, and who are fearful of what the future holds for them outside the centers. The problem of relocating them is not a simple one.

There are many other children, of course, who have grown beyond school age, and thousands of the young men are now fighting, or training to fight for the same principles and ideals that other American boys are fighting to defend on battlefields around the world. Many of these American soldiers of Japanese ancestry have parents who are still living in relocation centers. Let me read you a portion of a letter written by an alien father to his son in the service.

He wrote: "Think not too cheaply of your life; live it as you can in the service of your country -- for what good is a lifeless soldier? Be ever careful, cautious, but never begrudge your life for your country -- be ever willing to die for her if need be. Then, and then only you have given your all, done your best, can I say that my son lived well."

Several thousand young American volunteers of Japanese descent, recruited from the American mainland and Hawaii, are now undergoing vigorous training to prepare them for battle against our Axis enemies. The officers who command them have repeatedly praised them for earnest and intelligent devotion to duty. In Italy, in the battle for Cassino and elsewhere, the fighting men of the 100th Infantry Battalion, composed of Americans of Japanese descent, have won the praise of their commanders for their valor in battle. Casualty lists, reported by the War Department, reveal that the battalion has suffered losses, in dead, wounded, and missing in action, exceeding 40 percent of the entire personnel. The Secretary of War has commended the unit for achieving "a creditable record of fighting efficiency."

Recently I read an editorial in a western newspaper which attacked the loyalty of all Americans of Japanese ancestry, while admitting that the nisei soldiers were making "a superficial showing of loyalty." It might be an enlightening experience for the writer of that editorial to visit some of the hospitals in the East and Middle-West where American boys of Japanese descent are recuperating from wounds received in Italy while fighting for the country that gives him the freedom to express his views. He might try to explain just what he meant by "superficial loyalty" to Yosh Omiya who lost his eyes when the American Fifth Army was fighting its way across the Volturno River. Yosh would not be able to read the editorial. Yosh will never see again.

I want to quote from a letter written by an American Army officer who was sent home among the wounded after seeing action with our Japanese American soldiers in Italy. You may have read it in the February 14 issue of _Time_ magazine. This officer wrote in part:

"There are a lot of people in these United States who have nothing but a one-track mind. In some of the articles of your Letters to the Editors (_Time_, Jan. 17) I saw some of these people in a true light.

"I just came from Italy where I was assigned to the Japanese 100th Infantry Battalion. I never in my life saw any more of a true American than they are...

"Ask anyone who has seen them in action against the Jerry (to) tell you about them. They'll tell you when they have them on their flanks they are sure of security in that section..."

There have been many other letters in the same vein from American officers and men who have fought side by side with our American soldiers of Japanese ancestry.

Many citations for service above and beyond the call of duty have been awarded to the nisei fighters. For example, Staff Sergeant Kasuo Kozaki, a noncommissioned officer of Japanese descent, has won the Silver Star for gallantry in action. On December 28, the War Department announced awards of the Purple Heart to 58 members of the 100th Infantry Battalion. There will be many more citations and awards worn by these boys when they come home again.

I know that many of you are familiar with the record of Sergeant Ben Kuroki who has twice been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, in addition to the Air Medal with four oak-leaf clusters, for his fighting exploits in the air over Nazi territory. In speaking before the Commonwealth Club of San Francisco, on February 4, Sergeant Kuroki had this to say: "In my own case, I have almost won the battle against intolerance; I have many close friends, in the Army now -- my best friends, as I am theirs -- where two years ago I had none. But I have by no means completely won that battle. Especially now, after the widespread publicity given the recent atrocity stories, I find prejudice once again directed against me, and neither my uniform nor the medals which are visible proof of what I have been through, have been able to stop it. I don't know for sure that it is safe for me to walk the streets of my own country." [See TIME Magazine articles, Ben Kuroki, American and The 59th Mission.]

It makes me sad to think that conditions could be found in America to prompt such a statement from a man who has participated in thirty bombing missions over Germany. I wonder what attitude the professional critics of all Japanese Americans will take toward Mr. and Mrs. Shiramizu of the Colorado River Relocation Center whose son, Sergeant James Shiramizu, died from wounds received in Italy a few weeks ago. Sergeant Shiramizu also left a young wife and a two-year-old son who are living in the center. I cannot believe that many real Americans would advocate deporting this family after the close of the war. Many of these boys I have been mentioning are volunteers. For nearly two years after Pearl Harbor, Americans of Japanese descent were not inducted through Selective Service until January 21, of this year, when the War Department announced that plans had been completed to receive them through the general Selective Service System. In explaining the order, the War Department said that "the excellent showing" made by the Japanese American combat team now in training, and "the outstanding record" achieved by the 100th Infantry Battalion in Italy were major factors for taking greater numbers of nisei into the armed forces.

Our records show that, up to the fourth of March, 107 boys have been accepted for Army service from the relocation centers. These inductees are credited, for the most part, to the Selective Service boards in the West Coast communities where they were living before the evacuation.

Despite the record of patriotic devotion achieved by nisei soldiers in the American Army, there are still a great many people in this section of the country and elsewhere who persist in believing that all persons of Japanese ancestry are basically disloyal to the United States. Because of the emotions aroused by the Pearl Harbor attack and the Pacific war, it has become extremely easy -- and, unfortunately, quite popular in some areas -- to attack all Japanese-Americans indiscriminately. The nisei boys and girls, along with their alien parents and their third-generation children, have become fair game for special interest groups who would like to deprive them permanently of their rightful place in our national life. The extremists participating in this campaign go so far as to advocate wholesale deportation; the more "moderate" element will apparently be satisfied if all people of Japanese descent are kept out of the Pacific coastal area.

We in the War Relocation Authority are fully aware that the forces advocating deportation or permanent exclusion of this minority group are energetic and resourceful. We know that many of the participants are tightly organized and that they have ample funds at their disposal. They have already made it quite clear that they will seize every opportunity to stir up popular fears and resentments against the entire group of Japanese descent in this country.

Much of the campaign is centered around attacks on the War Relocation Authority. The Hearst press, for example, has used almost every conceivable device to create the impression that WRA is incompetent, lax in its administration, and excessively sympathetic toward the evacuees. Naturally we cannot agree with these charges. In the last analysis, I sincerely doubt whether the Hearst press and the other opposition forces are much concerned about our comparatively small organization. The real target, in my judgment, is the evacuees. Attacks aimed at WRA are merely an indirect method of fomenting antagonisms against the people in the relocation centers.

One of the most popular lines of attack is the charge that people in relocation centers are being provided with luxurious foods and that they are eating at government expense far better than the average American family. In these days, when all of us are tightening our belts just a little and going without some of our favorite peacetime dishes, such an allegation obviously has tremendous emotional possibilities. It hits the average citizen in a highly vulnerable spot and has stimulated many people who are normally quite mild-mannered into almost incoherent hatred and anger. The only trouble with this charge is that it is completely without foundation. Gradually, as a result of eye-witness news stories coming out of relocation centers, more and more people are coming to realize this fact, and the charge is losing much of its former potency. But I feel sure we in WRA have not heard the last of it yet, much as we should like to.

Another line of approach is to disseminate the idea that WRA's leave procedures are lax and inadequate, and that we are deliberately or needlessly turning potential spies and saboteurs loose upon the Nation. This is one of the most deadly of all the opposition charges since it appeals to one of the most elemental of human emotions -- the emotion of fear. But like the food charge, it is utterly untrue. Actually, as I indicated earlier, we have gone to great lengths in our efforts to safeguard the national security and we have taken every feasible precaution in granting leave permits under the relocation program.

Still another charge is perhaps the most popular of all. This is the allegation that WRA is pampering and coddling the people at relocation centers. Now, those are extremely vague terms, and I don't suppose we ever will be completely successful in nailing down this charge. As long as disgruntled former employees of WRA who were discharged for incompetence continue to pour out their resentments publicly, the accusation of "social-mindedness" will probably go on appearing with monotonous regularity in the public prints. It is interesting to note, however, that a member of the Japanese Diet was recently quoted in a propaganda broadcast as complaining that American internees in the Far East are being treated "too generously."

There is still another assertion of the race baiters that needs some attention -- the assertion that Japanese-Americans returning to the West Coast, when the military necessity for exclusion has ended, will be mobbed and forced to leave. The District Attorney of Los Angeles County, for example, is reported to have said that he has received letters from three organizations informing him that the members have "pledged to kill any Japanese who comes to California now or after the war." If we have come to the point where threats of murder against some of our own citizens are made as a means of discouraging their freedom of movement, then I think it is time we re-examine our national conscience.

Fundamentally, the campaign against Americans of Japanese ancestry is a campaign of hate. The forces leading this drive have deliberately set out to foster mass hatred, and in many parts of this State they have already reaped a bumper crop. One of their favorite devices is to identify the people in relocation centers as closely as possible with our real enemies across the Pacific. Basically, this strategy is a denial of the potency of American institutions. It assumes that merely because an individual is of Japanese extraction, he is somehow immune to the effect of our public school system and of all the other Americanizing influences that operate in a normal community. Let me say emphatically that I have more faith than that in the strength of our American institutions. And I feel positive that they have been far more influential in molding the minds of the nisei than the transplanted institutions of Japan.

Now I want to read a quotation that may possibly have a familiar ring to a California audience:

"This organization places itself squarely on the record as absolutely opposed to the release of any Japanese, either alien or American born. We urge our Senators and Congressmen to use their influence with the national administration and the War Relocation Authority to discontinue this dangerous practice immediately, and forthwith to recall any and all Japanese who have heretofore been released for any purpose from the relocation centers... We strongly urge that all Japanese, both alien and American born, be kept in relocation centers in the interior of the United States, under the supervision and control of the Army, instead of civilian authorities, for the duration of the war."This resolution, with not a word changed, has been endorsed by one West Coast organization after another. Not only does it ignore the constitutional questions involved in the measures advocated by it; if it were adopted into national policy, it would mean the return to civilian life and imprisonment of thousands of Japanese American boys who are fighting for democracy. It would mean the detention of many American citizens who are engaged on government assignments to gather information regarding our enemy across the Pacific. It would mean the loss of thousands of workers who are helping to produce food and materials for our fighting men.

Resolutions of a closely similar nature have been passed by many other organizations; Chambers of Commerce, posts of the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, local unions of the American Federation of Labor. Almost without exception, they wholly disregard the legality of their proposals and the purposes for which the War Relocation Authority was created.

The stimulators of racial fanaticism in this section of the country have sometimes hampered the program of the War Relocation Authority, but we have always proceeded firm in the belief that the great majority of the American people still cherish, undiminished, the principles of justice and freedom that inspired the founding of our Nation. Our concern reaches far beyond protecting the rights of the people of Japanese ancestry. The rights of other minorities are equally at stake in what we do with these people. We cannot allow one minority to be sacrificed on the altar of wartime emotionalism without jeopardizing the rights of other minorities. The danger lies in setting a precedent that might later be extended to the denial of rights for other racial groups, religious minorities, and even political minorities. Our failure to meet the responsibility that has been placed upon us would go far toward destroying the constitutional safeguards that guarantee equal protection to all of us who live on American soil.

We are also deeply concerned about the welfare of thousands of Americans who are now prisoners of war in Japan. The quick attempt of the Japanese propagandists to offset the revelation of atrocities in the Philippines by charging us with mistreatment of Japanese aliens in America should be evidence enough that they are watching us. We dare not provide them with incidents which would assist them in justifying their brutality before the civilized world.

The most immediate concern for all of us is, of course, to win the war. We need to direct every ounce of our energy into fighting and conquering the evil forces in Japan and Germany that forced the war upon us. I do not hesitate to say that any newspaper, any organization, any individual that undertakes to deflect our attention away from the real enemies that threaten the future of our nation, by fomenting false issues and creating dissension among us, is un-American in spirit and in deed. These elements striving to identify American citizens with the Japanese enemy simply on the basis of a common racial origin are fomenting a false issue; they are creating dissension as regrettable as it is unnecessary.

The War Relocation Authority in the execution of its responsibilities is working to preserve the principles of justice and equality guaranteed in the Constitution of our country. We are working to uphold the principles of human decency that distinguish civilization from barbarism. There are some people among us, more especially here in California and other parts of the West, whose main criticism of the War Relocation Authority is that we are striving to provide humane treatment for the people in our relocation centers, while Americans imprisoned by Japan are tortured, starved and reviled. They accuse us of pampering and coddling because we have not allowed the brutality of the Japanese enemy to influence our policies and program. I say to them: No, we have not taken Japan as a model -- thank God!

We are working to the best of our ability to avoid conditions and incidents that might encourage the Japanese enemy to inflict more suffering on Americans imprisoned by them. We are looking to the future with an earnest hope that our efforts may greatly minimize the postwar problem of readjusting our Japanese American population into normal living. There is no need for the problem to be difficult if it is handled with intelligence and courage.

I have no apologies to make for the program of the War Relocation Authority. I believe it is a sound program and that we are conducting our operations in accord with the best principles of our American heritage. Despite the opposition, we have every intention of continuing on that basis.

-- Table of

Contents --