Time Magazine

Monday, Oct. 18, 1948Not Worth Living

Last week in the Federal District Court in Los Angeles, a U.S. citizen was sentenced to die as a traitor to the U.S. In all U.S. history, only a handful of traitors have heard that sentence. None has actually been executed as a traitor to the U.S.

The traitor was a bespectacled, wiry, 27-year-old Nisei named Tomoya Kawakita, better known to hundreds of G.I. prisoners as "The Meatball." The son of a California grocer, Kawakita was caught on a visit to Japan by World War II. He threw in his lot with the Japanese. As an interpreter in the prison camp at Oeyama, he taunted G.I. prisoners in their own ball-park English, took savage delight in beating and tormenting them.

During his three-month trial, veterans trooped to the stand to tell how he had forced them to beat each other, made them work when they were sick, beat one man into temporary insanity. After the war, Kawakita returned to California. He was studying at the University of Southern California when a former Oeyama inmate spotted him in a Los Angeles store.

In pronouncing sentence, Federal District Judge William C. Mathes declared grimly: "His life, if spared, would not be worth living. The only worthwhile use for the life of a traitor is to serve as an example to those of weak moral fiber who might hereafter be tempted to commit treason against the U.S." Unless a higher court reverses the verdict or the President intervenes, he will die in the San Quentin gas chamber.

[NOTE: His death sentence was commuted to life in prison by Pres. Eisenhower. Pres. Kennedy stripped him of his U.S. citizenship and deported him to Japan.]

Suspense of the long trial is over and Tomoya Kawakita, 27, hears his conviction as traitor against the United States of America. With him is his attorney, Morris Lavine. Jury was made up of nine women and three men.

(Los Angeles Times, September 3, 1948 - Photo copyright owned by UC Regents )

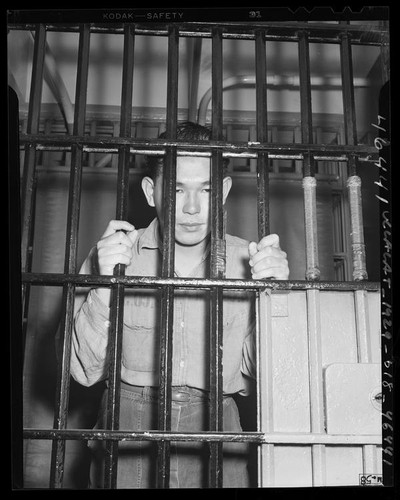

Tomoya Kawakita behind bars in the Los Angeles County Jail, 1947

"RECKONING DUE: Tomoya Kawakita remained sullenly behind bars in the County Jail yesterday while authorities collected evidence against him by former servicemen who identified him as cruel foreman of Jap prison camp."

(Photo copyright owned by UC Regents)

Los Angeles Times

September

20, 2002

ON THE LAW

POW Camp Atrocities Led to Treason Trial

ON THE LAW

POW Camp Atrocities Led to Treason Trial

Tomoya Kawakita claimed dual citizenship, abusing captured GIs in Japan in World War II, then moving to the U.S.

DAVID ROSENZWEIG, TIMES STAFF WRITER

Army veteran William L. Bruce, a survivor of Corregidor, the Bataan death march and three years in a Japanese prisoner of war camp, couldn't believe his eyes as he shopped with his bride one autumn day in 1946 at the Sears department store in Boyle Heights.

Standing a few aisles away amid the crush of shoppers in that quintessentially American setting was the man responsible for brutalizing Bruce and scores of other GIs held captive in Japan's Oeyama prison camp on Honshu Island.

Tomoya Kawakita, who held dual citizenship in the U.S. and Japan, served as an interpreter and self-appointed taskmaster at the camp, earning the nickname "Efficiency Expert" for his methods of inflicting pain on inmates weakened by malnourishment and forced labor.

"I was so dumbfounded, I just halted in my tracks and stared at him as he hurried by," Bruce, then 24 and attending college under the GI Bill, said shortly after the encounter.

"It was a good thing, too," said the former artilleryman. "If I'd reacted then, I'm not sure but that I might have taken the law into my own hands--and probably Kawakita's neck."

Instead, Bruce followed him outside the store, jotted down the license plate number of his car and notified the FBI.

Kawakita, who had returned to the United States after the war and enrolled at USC, was tried and convicted of treason in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles and sentenced to death.

The sentence was never carried out. In 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, responding to appeals from the Japanese government, commuted Kawakita's death sentence to life in prison. In 1963, President John F. Kennedy ordered him freed after 16 years behind bars on the condition that he be deported to Japan and never return.

Now more than half a century since his trial, Kawakita holds the distinction of being the last person prosecuted for treason against the United States.

He was represented at his federal court trial by Morris Lavine, a colorful Los Angeles criminal defense lawyer, who was fond of describing himself as "attorney for the damned." Lavine's clients ranged from the indigent, whom he represented at no charge, to the likes of mobsters Mickey Cohen and Johnny Roselli, and Teamsters boss James Hoffa.

Heading the prosecution team was U.S. Atty. James M. Carter, who went on to become a federal appeals court judge.

More than a dozen former POWs testified against Kawakita. They described how he forced prisoners to beat one another, and then beat those he thought didn't hit the other prisoners hard enough. They accused him of forcing prisoners to run laps until they collapsed in exhaustion simply because they had finished their work assignments early.

The camp was set up next to a nickel ore mine and processing plant, where most of about 400 American POWs were forced to work. Kawakita was employed by the mining company.

Once, he forced a prisoner to carry a heavy log up an icy slope. The prisoner fell and suffered a serious spinal injury. Fellow POWs testified that Kawakita waited five hours before summoning help for the injured American.

They also recalled being taunted by Kawakita with comments such as: "We will kill all you prisoners right here anyway, whether you win the war or lose it."

And, "You guys needn't be interested in when the war will be over, because you won't go back. You will stay here and work. I will go back to the States because I am an American citizen."

Kawakita's citizenship proved to be a crucial issue during the trial and subsequent court appeals.

By definition, treason can be committed only by someone owing allegiance to the United States.

Born in Calexico to Japanese parents, Kawakita held dual citizenship under U.S. and Japanese laws. In 1939, at the age of 18, he went to Japan to attend school. He remained there after the outbreak of war, graduating from Meiji University.

At the trial, Lavine advanced a novel argument. As a dual U.S. and Japanese citizen, he argued, his client owed exclusive allegiance to the country in which he resided. In this case, Japan. Lavine also contended that Kawakita had effectively renounced his U.S. citizenship by signing a family census register maintained by Japanese authorities.

In his instructions to jurors, U.S. District Judge William C. Mathes made it clear that if they found that Kawakita genuinely believed he was no longer an American citizen, then they must acquit him of the treason charges.

Sequestered during deliberations, the jury struggled mightily to resolve the question--declaring several times that they were hopelessly deadlocked. But ultimately they found Kawakita guilty on eight of 13 overt acts of treason charged by the prosecution.

When he appeared for sentencing, Kawakita continued to insist he was innocent. "As I have been found guilty by the jury, I ask your honor for mercy," he said.

By law, Mathes had leeway to impose a sentence ranging from a minimum of five years in prison to a maximum of death at Alcatraz.

He chose the latter, saying: "Reflection leads to the conclusion that the only worthwhile use for the life of a traitor, such as this defendant has proved to be, is to serve as an example to those of weak moral fiber who may hereafter be tempted to commit treason against the United States."

Today, most of those involved in the case are either dead or, if alive, could not be located. One exception is William J. Kelleher, then a federal prosecutor and now a senior U.S. District Court judge in Los Angeles.

Although he did not take part in the trial, Kelleher was assigned to draft the government's response to Kawakita's appeal of his conviction. As a result, he immersed himself in every detail of the case.

In an interview last week , Kelleher recalled being visited at his office by Bruce and two other former POWs while he was working on his brief for the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

"Me and the boys had a little meeting last night," he said Bruce told him. "And we want you to know that if he ever gets out, we'll be waiting for him."

Fortunately, Kelleher said, the appeals court upheld Kawakita's conviction by a 3-0 vote.

It was a much closer call when the appeal went before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1952. The vote was 4 to 3 to uphold the conviction. Two of the court's nine justices disqualified themselves.

At the crux of the case was this question: Where does the allegiance of a dual citizen lie when two nations, each claiming his loyalty, go to war?

"Of course, a person caught in that predicament can resolve the conflict of duty by openly electing one nationality or the other," said Justice William O. Douglas, writing for the majority.

Kawakita, the court said, chose neither option, trying instead to hedge his bets on the war's outcome while freely performing acts of hostility against the U.S.

"One who wants that freedom can get it by renouncing his American citizenship," Douglas wrote. "He can not turn it to a fair-weather citizenship, retaining it for possible contingent benefits but meanwhile playing the role of the traitor. An American citizen owes allegiance to the United States wherever he may reside."

See also:

TOMOYA KAWAKITA v. UNITED STATES, UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS, NINTH CIRCUIT, 190 F.2d 506; 1951

U.S. Supreme Court, KAWAKITA v. UNITED STATES, 343 U.S. 717 (1952)

Densho Encylopedia article on Tomoya Kawakita

-- Table of

Contents --