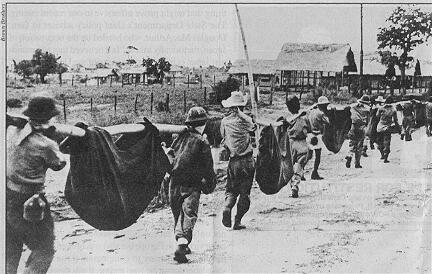

Parade Magazine U.S. soldiers who surrendered to the Japanese during World War II were ordered by our own government not to talk about the atrocities they endured as POWs. Now, says California Rep. Mike Honda...'They Should Have Their Day In Court'by Peter Maas Tears suddenly fill Lester Tenney's eyes. "I'm sorry," he says. "It's been a long time, but it's still very hard sometimes to talk about." All I can do is nod dumbly. Words fail me as I listen to the horror he is describing. On April 9, 1942, Tenney, a 21-year-old Illinois National Guardsman, was one of 12,000 American soldiers who surrendered to the Japanese at the tip of Bataan Peninsula, which juts into Manila Bay in the Philippines. Ill-equipped, ill-trained, disease-ridden, they had fought ferociously for nearly five months against overwhelming odds, with no possibility of help, until they ran out of food, medical supplies and ammunition. As prisoners of war, Tenney among them, they were taken to a prison camp by the Japanese army on what became infamous as the nine-day, 55-mile-long Bataan Death March, during which 1000 of them perished. The atrocities they suffered have to some extent been revealed. But what happened afterward -- - when they were forced into inhuman slave labor for some of Japan's biggest corporations -- - remains largely unknown. These corporations, many of which have become global giants, include such familiar names as Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Kawasaki and Nippon Steel.

Subjected to forced labor and brutality in Japanese mines, these men, some say, are entitled to long-delayed justice.

Through interviews with former POWs and examinations of government records and court documents, I learned that in 1999 Tenney had filed a lawsuit for reparations in a California state court. His suit was followed by a number of others by veterans who had suffered a similar fate. The Japanese corporations, instead of confronting their dark past, went into deep denial. Represented by American law firms, they maintained that, by treaty, they didn't owe anybody anything -- not even an apology. Surprisingly, the U.S. government stepped in on behalf of the Japanese and not only had these lawsuits moved to federal jurisdiction but also succeeded in getting them dismissed by Vaughn R. Walker, a federal judge in the Northern District of California. In his ruling, Judge Walker declared in essence that the fact that we had won the war was enough of a payoff. His exact words were: "The immeasurable bounty of life for themselves [the POWs] and their posterity in a free society services the debt." In applauding the judge's decision, an attorney for Nippon Steel was quoted as saying, "It's definitely a correct ruling." She did not dwell on what these men had gone through. What befell Lester Tenney as a POW was by no means unique. He got an inkling of what was to come on that April day in 1942 when he surrendered and one of his captors smashed in his nose with the butt end of a rifle. Forced to stumble along a road of crushed rock and loose sand, the men wracked with malaria, jaundice and dysentery -- were given no water. Occasionally, they would pass a well. Anyone who paused to scoop up a handful of water was more likely than not bayoneted or shot to death. The same fate awaited most POWs who could no longer walk. "If you stopped," Tenney recalls, "they killed you." As Tenney staggered forward, he saw a Japanese officer astride a horse, wielding a samurai sword and chortling as he tried, often successfully, to decapitate POWs. During a rare respite, one prisoner was so disoriented that he could not get up. A rifle butt knocked him senseless. Two of his fellow POWs were ordered to dig a shallow trench, put him in it and bury him while he was still alive. They refused. One of them immediately had his head blown off with a pistol shot. Two more POWs were then ordered to dig two trenches -- one for the dead POW, the other for the original prisoner, who had begun to moan. Tenney heard him continue to moan as he was being covered with dirt. Tenney was one of 500 POWs packed into a 50-by-50-foot hold of a Japan bound freighter. The overhead hatches were kept closed except when buckets of rice and water were lowered twice daily. Each morning, four POWs were allowed topside to hoist up buckets of bodily wastes and the corpses of anyone who had died during the night, which were tossed overboard. In Japan, the prisoners were sent to a coal mine about 35 miles from a city they had never heard of called Nagasaki. The mine was owned by the Mitsui conglomerate, which is today one of the world's biggest corporations. You see the truck containers it builds on every highway in America. The mine was so dangerous that Japanese miners refused to work in it. The Geneva Convention of 1929 specified that the POWs of any nation "shall at all times be humanely treated and protected" and explicitly forbade forced labor. Japan, however, never ratified the treaty. That was how it justified putting POWs to work during World War II, freeing up able-bodied Japanese men for military service. Lester Tenney and his fellow POW slave laborers worked l2-hour shifts. Their diet, primarily rice, amounted to less than 600 calories a day. This was subsequently reduced to about 400 calories. When he was taken prisoner, Tenney weighed 185 pounds. When he was liberated in 1945, he weighed 97 pounds.

The barbarities of the Bataan Death March have been revealed. What happened afterward is largely unknown.

Vicious beatings by Mitsui overseers at the mine were constant. Tenney's worst moment came when two overseers decided he wasn't working fast enough and went at him with a pickax and a shovel. His nose was broken again. So was his left shoulder. The business end of the ax pierced his side, just missing his hip bone but causing enough internal damage to leave him with a permanent limp. Frank Bigelow was a Navy seaman on the island fortress of Corregidor in Manila Bay. It was lost about a month after Bataan fell, so Bigelow escaped the Death March. But he ended up in the same Mitsui coal mine as Tenney. He was in the deepest hard-rock part of the mine when a boulder toppled onto his leg, snapping both the tibia and fibula bones 6 inches below the knee. A POW Army doctor, Thomas Hewlett, was refused plaster of Paris for a cast. Hewlett tried to construct a makeshift splint, but it didn't work. Bigelow's leg began to swell and become putrid. Tissue destroying gangrene had set in. With four men holding Bigelow down, Hewlett-performed an amputation without anesthesia, using a razor and a hacksaw blade. Bigelow recalls: "I said, 'Doc, do you have any whiskey you could give me?' And he said, 'If I had any, I'd be drinking it myself.'" To keep the gangrenous toxins from spreading, Hewlett packed the amputation with one item readily available in the prison camp -- maggots. Bigelow still can't comprehend how he withstood the excruciating pain. "You don't know what you can do 'til you do it," he says. Another seaman, George Cobb, was aboard the submarine Sealion in Manila Bay when it was sunk in an air attack three days after Pearl Harbor. Cobb was shipped to a copper mine in northern Japan owned by the Mitsubishi corporate empire. Clad only in gunnysack like garments, the POWs had to trudge to the mine through l0-foot-high snowdrifts in bitter winter cold. Of 10 captured Sealion crewmen, Cobb is the sole survivor. "I try not to remember anything," he says. "I want it to be a four-year blank." One day in August 1945, Lester Tenney and his fellow POWs saw a huge, mushroom-shaped cloud billowing from Nagasaki. None of them, of course, knew it was the atom bomb that would end the war. They found out on Aug. 15 that Japan had surrendered when they were given Red Cross food packages for the first time during their long captivity. They then found a nearby warehouse crammed with similar packages and medical supplies that had never been distributed. They also would learn that the Japanese high command had a master plan to exterminate all the POW slave laborers, presumably to cover up their horrible ordeal. After the POWs returned home, they were given U.S. government forms to sign that bound them not to speak publicly about what had been done to them. America was in a geopolitical battle with the Soviet Union and, later, Red China for the hearts and minds of the postwar Japanese and did not want to do anything that might prove offensive to our recent enemy. The State Department's chief policy adviser to Gen. Douglas MacArthur, who headed up the occupation of Japan, rhetorically asked: "Is it believed that a Communist Japan is in the best interests of the United States?" But Tenney, possibly because of his extended hospitalization, never got one of those forms. In 1946 he wrote a letter to the State Department citing his experience and requesting guidance on how to mount claims against those who had beaten, tortured and enslaved him. The State Department replied that it was looking into the matter and advised him not to retain an attorney. Hearing nothing further, Tenney, a high school dropout, decided to get on with his life. He eventually earned a Ph.D. in finance and taught at both San Diego State University and Arizona State University. Meanwhile, the U.S. and Japan finalized a peace treaty in 1951. Two years ago, Tenney read that the U.S. government not only had successfully worked on behalf of Holocaust victims in Europe but also was brokering an agreement with Germany to compensate those forced into slave labor during the Nazi regime. It was then that he filed his own lawsuit against Mitsui. The U.S. State Department and Justice Department intervened for the Japanese corporate defendants on the basis of the 1951 treaty, a clause of which purports to waive all future restitution claims. But the treaty contains another clause which the U.S. government to date has chosen to ignore, stating that all bets would be off if other nations got the Japanese to agree to more favorable terms than our treaty. Eleven nations -- including the then Soviet Union, Vietnam and the Philippines -- got such terms. There is still hope for the surviving POWs, their widows and heirs. Last March, two California Congressmen, Republican Dana Rohrabacher and Democrat Mike Honda, co-sponsored a bill (H.R. 1198) calling for justice for the POWs.

Notably, Honda is a Japanese-American who, as an infant, was interned by the U.S. with his mother and father during World War II. The U.S. has since paid each surviving internee $20,000 in restitution and, perhaps more important, acknowledged that the internment was wrong. "I believe," Honda told me, "that these POWs not only fought for their country but survived, and now they are trying to survive our judicial system. They should have their day in court." Contributing Editor Peter Maas' latest best-seller, "The Terrible Hours," about a rescued sub, is now in paperback.

If You Want To HelpTo express your feelings about the POW bill (H.R. 1198), write or e-mail Rep. Michael Honda, 503 Cannon House Office Bldg., Washington, D.C. 20515 (mike.honda@mail.house.gov) or Rep. Dana Rohrabacher, 2338 Rayburn House Office Bldg., Washington, D.C. 20515 (Dana@mail.house.gov). Or write to your own Representative or Senators. You can find the addresses you need at www.house.gov for your Representative and at www.senate.gov for your Senators. |

LESTER TENNEY

LESTER TENNEY FRANK BIGELOW

FRANK BIGELOW GEORGE COBB

GEORGE COBB

HOPE FOR

RESTITUTION

HOPE FOR

RESTITUTION