People Magazine

"Up Front"

December 24, 2001

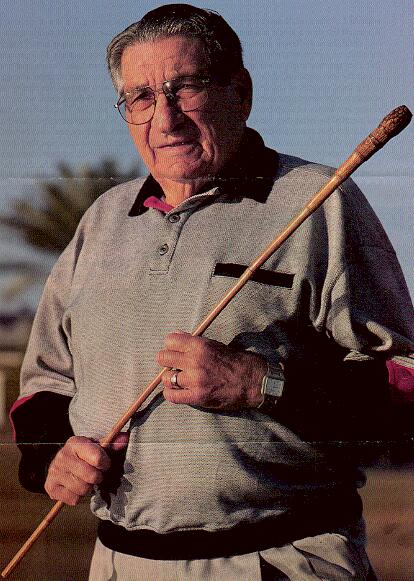

"The Japanese never said they were sorry," Tenney (with a punishing cane)

says of his enslavement. "I want an apology."

LESTER TENNEY'S 60-YEAR WAR

Imprisoned by the Japanese, an American POW aims to settle a wartime injustice

by

Alex Tresniowski

Lyndon Stambler (in Phoenix)

He carries the simple bamboo cane with him wherever he travels. Smoothed

and rounded at one end, it looks harmless enough, until Lester Tenney snaps

it to show the type of blow it can deliver. Nearly 60 years ago Japanese

soldiers used similar canes to beat Tenney and other Americans during the

hellish Bataan Death March, one of World War II's most infamous atrocities.

"The Japanese killed you if you stopped along the road," remembers Tenney,

81, one of about 12,000 American prisoners of war forced to take the march

in 1942. "If you couldn't walk anymore, they'd bayonet you or cut your head

off."

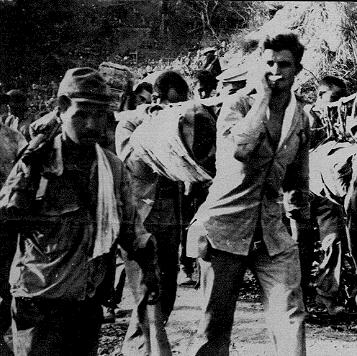

"It was pretty rough to watch," Tenney says of the brutal torture during

the Bataan Death March (in a Japanese photo)

Tenney was one of the lucky survivors of the 12-day, 86-mile ordeal, which

claimed the lives of as many as 1,000 Americans. But while he still has

nightmares about the march, it is what happened afterward that most deeply

haunts Tenney. Along with thousands of fellow POWs, he was enslaved for 2½

years and forced to work 12-hour days in a Japanese coal mine owned by Mitsui

& Co., one of Japan's largest conglomerates.

For years now Tenney has led a movement to seek unpaid wages and an apology

for the enslavement. "If you're a soldier, you accept certain things," he

says. "If you're killed, that's part of war. But it was not part of war to

put me in that coal mine and treat me the way they did. I feel I am entitled

to wages I was denied."

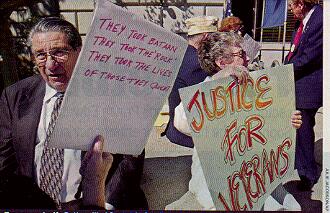

Tenney and wife Betty rallied Sept. 5 in San Francisco

with veterans seeking restitution.

Getting those wages has been an uphill battle. After first petitioning the

U.S. government for help in 1946, Tenney got nowhere for decades. (He did

receive about $1,800 from the U.S. government in the mid-1950s for lack of

food during the war.) Then a 1999 California law extended the statute of

limitations for slave labor claims against Germany and its allies to the

year 2010. Tenney, a retired finance professor, promptly sued Mitsui. Lawyers

for the company would not comment but argue in a statement that the company

was formed after the war and that a different Mitsui ran the mines. Tenney's

lawyers dispute that.

Last year a federal judge dismissed his case, citing the 1951 peace treaty

between the U.S. and Japan that barred private claims against the Japanese

government. Tenney is appealing that decision but inthe meantime has turned

to state court, inspiring claims on behalf of 5,000 surviving POWs and thousands

of heirs againstMitsui and other Japanese companies. On Oct. 19 California

superior court judge William McDonald allowed those suits to go forward.

The ruling "was the best news we've ever had," says Tenney. "I can now say

our government is honestly trying to solve this in an honorable

way."

Tenney's patriotism runs deep. The youngest of seven children born in Chicago

to Gus Tenenberg, a sales manager for the Liquid Carbonic Company, and Fannie,

a homemaker, he enlisted in the National Guard in 1940 and trained as a

tank-radio operator at Fort Knox, Ky. He eloped with his sweetheart of four

years, Clara Laks, just weeks before he shipped out to the Philippine island

of Luzon in October 1941. The day after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Japanese

bombers strafed U.S. installations in the Philippines. Tenney's battalion,

overwhelmed by thousands of Japanese troops, retreated to the Bataan peninsula.

Stranded with little food or supplies, the American troops surrendered four

months later. The next day Japanese soldiers broke Tenney's nose and some

of his teeth when he failed to respond to a question he did not understand.

Soon after, an estimated 12,000 Americans and 68,000 Filipino refugees began

the march to prison camps. Suffering from malaria and dysentery, Tenney survived

by focusing on his next step. "I had a positive attitude," he says. "I never

thought I was going to die."

Some months later Tenney was crammed onto a boat --- one of several since

referred to as hell ships ---for a 32-day journey to Japan. In the town of

Omuta, he was put to work in a mine shoveling coal for 12 hours a day. Again

he was routinely beaten by Japanese coworkers, he says. Coal mining is hazardous,

but the Americans did "absolutely the most dangerous work you can do," says

fellow POW Frank Bigelow, who lost a leg in a mining accident.

Then in August 1945, the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki,

and Japan surrendered. Tenney, 90 lbs. lighter than his normal weight of

185, was flown to Okinawa, where he was greeted by his brother William. It

was then he discovered that Clara, unsure if he was dead or alive, had remarried.

"I lived because I constantly thought of a life with her," says Tenney. "I

played like it didn't bother me, but it tore me up."

A

high school dropout, Tenney returned to school and eventually earned a Ph.D.

from USC and taught finance at Arizona State University, retiring in 1983.

He has a son, Glenn, with Mildred Wailer, whom he married in 1947 and divorced

in the mid-'5Os. He wed current wife Betty Straus in 1960, inheriting her

two sons. The couple, who have eight grandchildren and two great grandkids,

split time between their La Jolla, Calif., residence and a winter home in

Phoenix. A

high school dropout, Tenney returned to school and eventually earned a Ph.D.

from USC and taught finance at Arizona State University, retiring in 1983.

He has a son, Glenn, with Mildred Wailer, whom he married in 1947 and divorced

in the mid-'5Os. He wed current wife Betty Straus in 1960, inheriting her

two sons. The couple, who have eight grandchildren and two great grandkids,

split time between their La Jolla, Calif., residence and a winter home in

Phoenix.

It is an outwardly tranquil existence, but Tenney still wakes up screaming

some nights, roiled by nightmares. Yet he harbors no bitterness toward Japan;

he has taken several recent trips there to visit an exchange student he and

Betty hosted and to lecture school groups on his POW experiences. "Lester's

story is so powerful," says David Casey Jr., his San Diego-based attorney,

"that unless the companies can defeat us on technicalities, they would never

let it be heard by an American jury." His relentless pursuit of lost wages,

Tenney makes clear, is simply something he feels is the right thing to do.

"Somewhere along the line these companies have to be responsible," he says.

"This is not about money. It's about honor and dignity."

"The lawsuit made him open up more" about his past,

Betty says of Tenney (at home). |