34th Tank Company

History

Company A, 194th

Tank

Battalion

On

February 10,1941 Brainerd's

34th Tank Company, Minnesota National Guard, commanded by Ernest B.

Miller,

was Federalized and ordered to Fort Lewis, Washington for training. At

Fort Lewis, the 34th Tank Company was combined

with units from St. Joseph, Missouri and Salinas, California and

re-designated as the 194th Tank Battalion.

Major Miller was appointed the battalion commander. On

February 10,1941 Brainerd's

34th Tank Company, Minnesota National Guard, commanded by Ernest B.

Miller,

was Federalized and ordered to Fort Lewis, Washington for training. At

Fort Lewis, the 34th Tank Company was combined

with units from St. Joseph, Missouri and Salinas, California and

re-designated as the 194th Tank Battalion.

Major Miller was appointed the battalion commander.

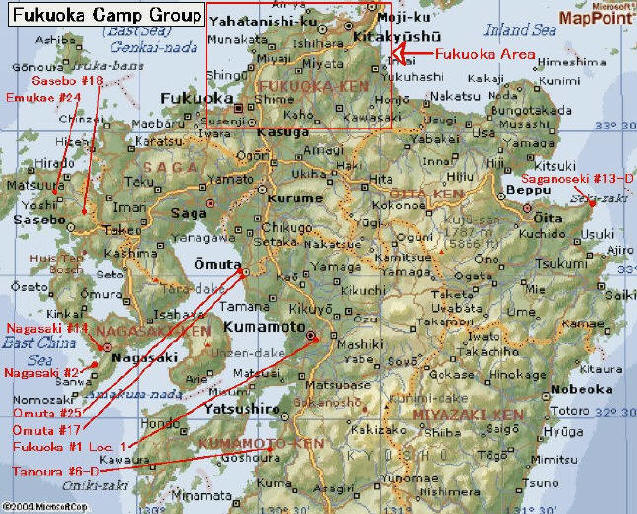

The 194th Tank Battalion, less Company B, was ordered to

reinforce the Philippine Islands arriving in Manila on September 26,

1941. The 194th was the first Tank unit in the Far East prior to

WWII. In August 1941, Company B had been reassigned to the Alaskan Defense Command.

This was the first Armored unit sent outside the Continental United

States.

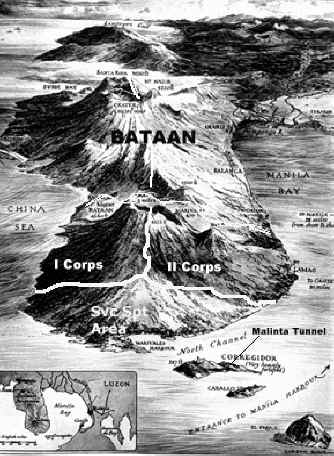

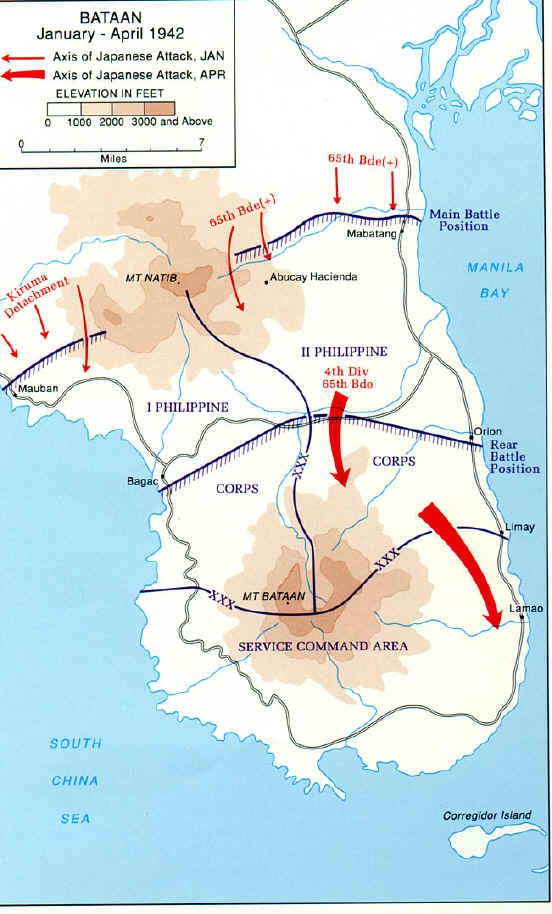

The 194th Tank Battalion was stationed at Fort

Stotsenburg

near Clark Field on the Island of Luzon,

where they trained until the outbreak of the war

on December 7, 1941. After the invasion of the Philippines by the

Japanese, the

Battalion was crucial to the beleaguered defense of

Luzon and the Bataan Peninsula.

The 194th held vital positions through out the Islands defense until

the fall of Bataan, on April 9,1942,

when ordered to surrender by General King. For their outstanding

performance of duty inaction,

the 194th Tank Battalion was awarded three Presidential Unit Citations.

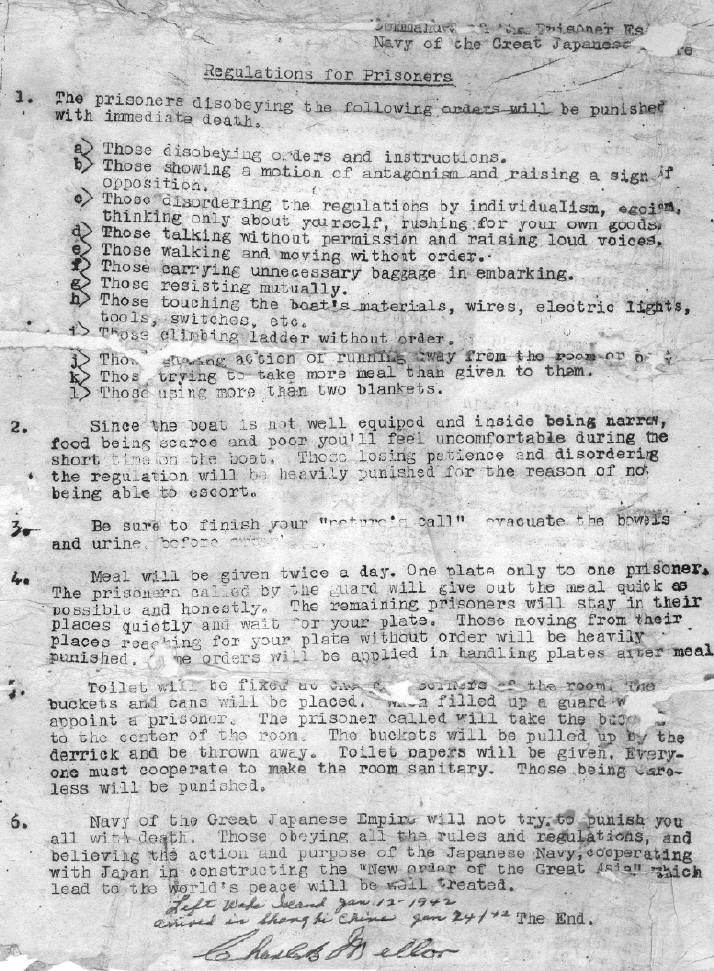

Following the surrender, the weakened and diseased

defenders,

including men of the 194th Tank Battalion,

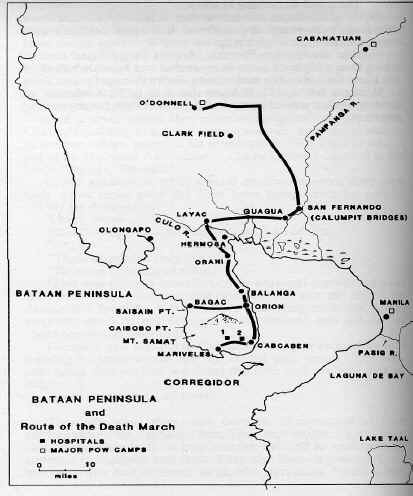

were ordered on the infamous Death March

by their Japanese captors. Prisoners on the Death March began marching

northward April 10, 1942 from Southern Bataan and terminated April

13,1942

at Camp O'Donnell.

The 194th prisoners were marched along with other prisoners from near

Mariveles to San Fernando, where they were packed into railcars and

moved to Capas, ending with a march to Camp O'Donnell. The prisoners,

without food or water, with extreme cruelty and atrocities dealt by the

Japanese, marched a total of 97 kilometers (or 60 miles).

Nearly 10,000 troops died, both American and Filipino.

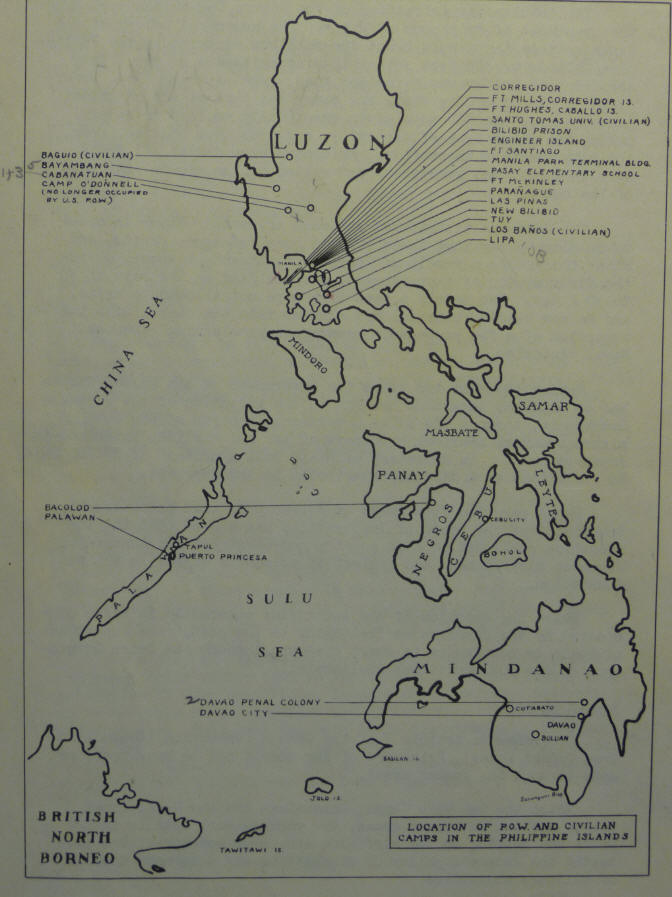

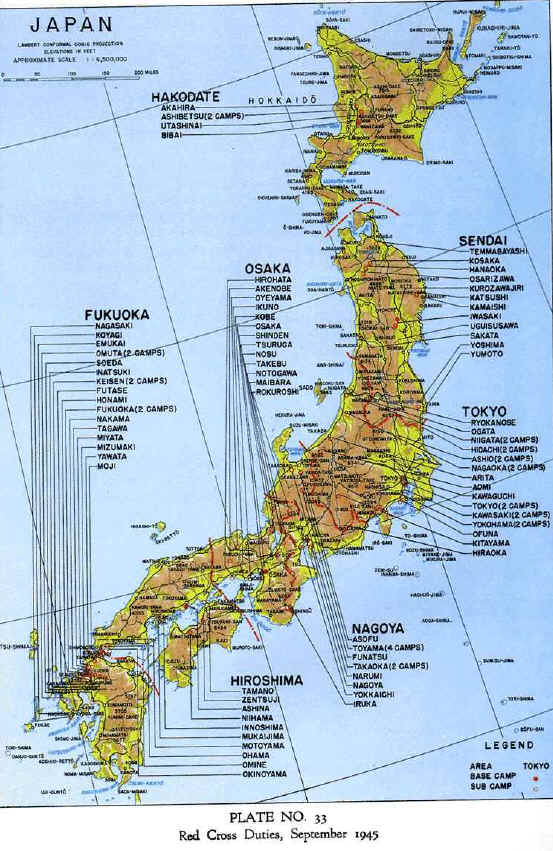

From Camp O'Donnell, where hundreds died, many prisoners

were

sent

to other camps in the Philippines. Designated POW's included men from

the 194th, who were eventually packed into the holds of unmarked

transports known as "HellShips". The prisoners were moved to labor

camps in Japan. Many of these unmarked POW "HellShips" in route to

Japan were sunk unknowingly by the US Navy,

killing many POW's.

Of the original 82 Officers and men of the3 4th Tank

Company who left

Brainerd, 64 accompanied the 194th overseas to the Philippines. One man

was wounded and evacuated, 2 to OCS, 3 were killed in action, 29 died

as POW’s, and 29 survived captivity.

Of the original 64 National Guardsmen, only 32 survived

to

return to Brainerd after the end of WWII.

(Credit: George Lackie, nephew to Warren

Lackie)

|