|

Archaebibliophilia

Occasional Postings of a Lover of Archaic Books

"a book... I have found" II Chron. 34:14,15

"knowledge delighteth thy soul" Prov. 2:10

Occasional Postings of a Lover of Archaic Books

"a book... I have found" II Chron. 34:14,15

"knowledge delighteth thy soul" Prov. 2:10

| <2018-2024 |

|

Cleaning out the old files...

October 30, 2025

Prov. 30: 32-33

"If thou hast been foolish in lifting thyself up, and if thou hast thought wickedly, lay thine hand upon thy mouth. When one churneth milk, he bringeth forth butter: and he that wringeth his nose, causeth blood to come out: so he that forceth wrath, bringeth forth strife."From A Commentary Upon the Holy Bible, Henry and Scott, Vol 3 (1833):

We must bridle and suppress our

own passion, and take shame to ourselves, whenever justly charged with

a fault. We must keep the evil thought we have conceived in our minds,

from breaking out in evil speeches. We

must not irritate the passions of others. Some are so provoking in

their words and conduct, that they make those about them angry, who are

not only not inclined to it, but resolved against it. Now this

forcing of wrath brings forth strife, and where that is, there is

confusion and every evil work. As in the churning of milk, and the

wringing of the nose, that is done by force, which otherwise would not

be done, so the spirit is heated by degrees with strong passions; one

angry word begets another, and so it goes on, till it ends in

irreconcilable feuds: let nothing therefore be said or done with

violence, but every thing with softness and calmness.

Four Biblical Principles

- It is always right to preach the gospel. II Tim. 4:2, I Peter 3 :15

- It is always wrong to aid and abet a program of unbelief. Eph. 5 :11.

- It is always wrong to pretend that an unbeliever is a Christian -- even if by such pretense the evangelist is able to preach to great crowds and some are saved. Romans 3:7-8.

- It is always wrong to be neutral when the Word of God is at stake. Rev. 3 :15-16.

Assorted Entries

|

Some thoughts on God's creation

Both the MICRO world and the MACRO world are infinite, for how small can one go to determine cause, or how far to determine extent? The subatomic particles vs. the universe... Are neutrinos capable of alteration in cell cohesion, i.e. to allow a physical object to pass through other physical objects, as Christ did? Or is that on a wholly different level of creation, as is the thought process? Even the electromagnetic and sound spectrums are infinite -- what is the largest wave, or the smallest? Re light -- is intensity infinite? Note the glory which filled the tabernacle and the temple after completion (Ex. 40:34 and ??). How bright can light be? What is the smallest photon? and the largest? The Two Effects of the Gospel

Excerpt from: A Sermon Delivered on May 27, 1855 by the REV. C. H. Spurgeon Now I must aim another blow at my antagonists the Arminians; I cannot help it. They will have it that sometimes the gospel is a savour of life unto death. They tell us that a man may receive spiritual life, and yet may die eternally. That is to say, a man may be forgiven, and yet be punished afterwards; he may be justified from all sin, and yet after that, his transgressions can be laid on his shoulders again. A man may be born of God, and yet die; a man may be loved of God, and yet God may hate him to-morrow. Oh! I cannot bear to speak of such doctrines of lies; let those believe them that like. As for me, I so deeply believe in the immutable love of Jesus that I suppose that if one believer were, to be in hell, Christ himself' would not long stay in heaven, but would cry, "To the rescue!" Oh! if Jesus Christ were in glory with one the gems wanting in his crown, and Satan had that gem, he would say, "Aha! prince of light and glory, I have one of thy jewels!" and he would hold it up, and then he would say, "Aha! thou didst die for this man, but thou hadst not strength enough to save him; thou didst love him once -- Where is thy love? It is not worth having, for thou didst hate him afterwards!" And how would he chuckle over that heir of heaven, and hold him up, and say, "This man was redeemed; Jesus Christ purchased him with his blood:" and plunging him in the waves of hell, he would say, "There purchased one see how I can rob the Son of God!" And then again he would say, This man was forgiven, behold the justice of God! He is to be punished after he is forgiven. Christ suffered for this mans sins, and yet," says Satan with a malignant joy, "I have him afterwards; for God exacted the punishment twice!" Shall that e'er be said? Ah! no. It is "a savour of life unto life," and not of life unto death. Go, with your vile gospel; preach it where you please; but my Master said, "I give unto my sheep ETERNAL life." You give to your sheep temporary life, and they lose it; but, says Jesus, "I give unto my sheep ETERNAL life, and they shall never perish, neither shall man pluck them out of my hands." I generally wax warm when I got to this subject, because I think few doctrines more vital than that of the perseverance of the saints; for if ever one child of God did perish, or if I knew it were possible that one could, I should conclude at once that I must, and suppose each of you would do the same; and then where is the joy and happiness of the gospel? Again I tell you the Arminian gospel is the shell without the kernel; it is the husk without the fruit; and those who love it may take it to themselves. We will not quarrel with them. Let them go and preach it. Let them go and tell poor sinners, that if they believe in Jesus they will be damned after all, that Jesus Christ will forgive them and yet the Father send them to hell. Go and preach your gospel, and who will listen to it? And if they do listen, is it worth their hearing? I say no; for if I am to stand after conversion on the same footing as I did before conversion then it is of no use for me to have been converted at all. But whom he loves he loves to the end. "Once in Christ, in Christ for ever;

Nothing from his love can sever." It is "a savour of life unto life." And not only, "life unto life" in this world, but of "life unto life" eternal. Every one who has this life shall receive the next life; for "the Lord will give grace and glory, and no good thing will he withhold from them that walk uprightly." The Eternal Name

Excerpt from: A Sermon Delivered on May 27, 1855 by the REV. C. H. Spurgeon We ask next, supposing Christ's gospel to become extinct, what religion is to supplant it? We inquire of the wise man, who says Christianity is soon to die, "Pray, sir, what religion are we to have in its stead? Are we to leave the delusions of the heathen, who bow before their gods, and worship images of wood and stone? Will ye have the orgies of Bacchus, or the obscenities of Venus? Would ye see your daughters once more bowing down before Thammuz, or performing obscene rites as of old?" Nay, ye would not endure such things; ye would say, "It must not be tolerated by civilized men." Then what would ye have? Would ye have Romanism and its superstitions? Ye will say, "No, God help us; never." They may do what they please with Britain; but she is too wise to take old Popery back again, while Smithfield lasts, and there is one of the signs of martyrs there; aye, while there breaths a man who marks himself a freeman, and swears by the constitution of Old England, we cannot take Popery back again. She may be rampant with her superstitions and her priestcraft; but with one consent my hearers reply, "We will not have Popery." Then what will ye choose? Shall it be Mahometanism? Will ye choose that, with all its fables, its wickedness and libiditiousness? I will not tell you of it. Nor will I mention the accursed imposture of the West that has lately arisen. We will not allow Polygamy, while there are men to be found who love the social circle, and cannot see it invaded. We would not wish, when God hath given to man one wife, that he should drag in twenty, as the companions of that one. We cannot prefer Mormonism; we will not, and we shall not. Then what shall we have in the place of Christianity? "Infidelity," you cry, do you, sirs? And would you have that? Then what would be the consequence? What do many of them promote? Communist views, and the real disruption of all society as at present established. Would you desire Reigns of Terror here, as they had in France? Do you wish to see all society shattered, and men wandering like monster icebergs on the sea, dashing against each other, and being at last utterly destroyed? God save us from Infidelity! What can you have, then? Naught. There is nothing, to supplant Christianity. What religion shall overcome it? There is not one to be compared with it. If we tread the globe round, and search from Britain to Japan, there shall be no religion found, so just to God, so safe to man. The Enchanted Ground

Excerpt from: A Sermon Delivered on February 3, 1856 By Rev. C. H. Spurgeon Dearly beloved, I have finished my sermon. There are some of you that I must dismiss, because I find nothing in the text for you. It is said, "Let us not sleep as do others, but let us watch and be sober." There are some here who do not sleep at all, because they are positively dead; and, if it takes a stronger voice than mine to wake the sleeper, how much more mighty must be that voice which wakes the dead. Yet even to the dead I speak; for God can wake them, though I cannot. O, dead man! dost thou not know that thy body and thy soul are worthless carrion? that whilst thou art dead thou liest abhorred of God, abhorred of man? that soon the vultures of remorse will come and devour thy lifeless soul; and, though thou hast lived in this world these seventy years (perhaps) without God and without Christ, in thy last hour the vulture of remorse shall come and tear thy spirit; and, though thou laughest now at the wild bird that circles in the sky, he will descend upon thee soon, and thy death will be a bed of shrieks, howlings, and wailings, and lamentations and yells! Dost thou know more still, that afterwards that dead soul will be cast into Tophet; and, as in the East they burn the bodies, so thy body and thy soul together shall be burned in hell? Go not away and dream that this is a metaphor. It is truth. Say not it is a fiction; laugh not at it as a mere picture. Hell is a positive flame; it is a fire that burns the body, albeit that it burns the soul, too. There is physical fire for the body, and there is spiritual fire for the soul. Go thy way, O man; such shall be thy fate. E'en now thy funeral pile is building, thy years of sin have laid huge trees across each other; and see, the angel is flying down from heaven with a brand already lit; thou art lying dead upon the pile; he puts the brand to the base thereof; thy disease proves that the lower parts are kindling with the flame; those pains of thine are the crackling of the fire. It shall reach thee soon, thou poor diseased one; thou art near death, and when it reaches thee thou shalt know the meaning of the fire that is unquenchable, and the worm that dieth not. Yet while there is hope I will tell thee the gospel. "He that believeth and is baptized shall be saved, and he that believeth not shall be," must be "damned." He that believeth on the Lord Jesus, that is, with a simple, naked faith, comes and puts his trust in him, shall be saved, without anything else; but he that believeth not shall inevitably -- hear it, men, and tremble -- he that believeth not shall assuredly be damned. P.S. It is frequently objected that the preacher is censorious: he is not desirous of defending himself from the charge. He is confident that many are conscious that his charges are true, and if true, Christian love requires us to warn those who err; nor will candid men condemn the minister who is bold enough to point out the faults of the church and the age, even when all classes are moved to anger by his faithful rebukes, and pour on his head the full vials of their wrath. IF THIS BE VILE, WE PURPOSE TO BE VILER STILL. ---C.H.S. The Kingly Priesthood of the Saints

Excerpt from: A Sermon Delivered on January 28th, 1855 by the REV. C. H. Spurgeon Now, to close up, one very practical inference. Ye are kings and priests unto your God. Then how much ought kings to give to the collection this morning? Thus speak ye to yourselves. "I am a king; I will give as a king giveth unto a king." Now, mark you, no paltry subscriptions! We don't expect kings to put down their names for trifles. Then, again: you are a priest. Well, priest, do you mean to sacrifice? "Yes." But you would not sacrifice a broken-legged lamb, or a blemished bullock, would you? Would you not select the best of the flock? Very right, then select the very best of the Queen's coins, and offer, if you can, sheep with golden fleece. Excuse my pressing this subject. I want to get this chapel enlarged; so do you; we are all agreed about it; we are all rowing in one boat. I have set my mind on 50 pounds, and I must, and will, have it to-day, if possible. I hope you won't disappoint me. It is not my own cause, but my Master's -- at other times you have given liberally -- I am not afraid of you -- but hope to come forward, next Sabbath morning, with the cheering announcement that the 50 pounds is all raised, and then I think my spirits will be so elevated, that, by the help of God, I will venture to promise you one of the best sermons I am capable of delivering. The Christian reader will be pleased to learn, that after this appeal, the sum of pounds 50 0s. 11½d. was collected at the doors, towards defraying the expenses of the enlargement. Should any reader of the New Park Street Pulpit desire to contribute to this excellent object, any sum will be thankfully received by MR. WILLIAM OLNEY, Secretary, at the Chapel. Faith

Excerpt from: A Sermon Delivered on December 14, 1856 by the REV. C. H. Spurgeon The old writers, who are by far the most sensible -- for you will notice that the books that were written about two hundred years ago, by the old Puritans, have more sense in one line than there is in a page of our new books, and more in a page than there is in a whole volume of our modern divinity -- the old writers tell you that faith is made up of three things -- first knowledge, then assent, and then what they call affiance, or the laying hold of the knowledge to which we give assent and making it our own by trusting in it. A Penitent Prince Mikasa

DR. PETER RUSSO, The Argus man, meets Hirohito's brother -- PRINCE OF NEW JAPAN Photo: The book that has shaken Japan -- Prince Mikasa's "Emperors, Graves, and People." The Prince wrote: "The war was an orgy of pillage, assault, arson, and rape." TOKYO, Tuesday Fool, coward, and double-crosser are some of the kindlier terms being used by nostalgic Japanese militarists to describe His Imperial Highness Prince Mikasa, the youngest brother of the Emperor. They hint also that, a few short years ago, before Japan's unnecessary surrender in the Pacific war, the Prince would have been patriotically disposed for the Imperial good. This ferocious outburst, expressed in pamphlets and letters to the Japanese Press, follows the publication of Prince Mikasa's book, "Emperors, Graves, and People." The book itself is a scholarly research into ancient Oriental history, but it is not the main subject matter which is wracking so many of Japan's devotees of the old Imperial Way. His Highness also saw fit to add a chapter entitled "My Recollections," and it is this long and soul-searching epilogue which has infuriated the traditionalists and made the book one of the most significant political and social documents of modern Japan. I read the book, found it enthralling, and decided to take the Prince up on the challenge it contained. Trading on my former associations with the Imperial universities of Japan, and my 25 years' friendship with Dr. Tatsunosuke Ueda, of the Imperial Academy, I invited the Prince to take pot luck with my wife and myself at our hotel. A slight deviation is necessary here to recall the kind of Imperial protocol which once obtained. Before the war there was about as much chance of getting an Imperial Japanese prince into a public dining-room as there was of taking Tibet's Dalai Lama on a round of Shanghai's nightclubs. The ancients of the Imperial Household, together with their administrative wardens, are still fighting a solid rearguard action against what they call the "democratic deterioration" of the Imperial rites. Exalted color They look with horror on the wicked modern necessity which now enables even lesser foreign diplomats to share members of the Imperial family on a pro rata basis, merely to get a bit of exalted color for their foolish diplomatic parties. Prince Mikasa, on the other hand, does not co-operate in this necessary diplomatic evil, and seems to have gone completely round the democratic bend. He has not only become a simple lecturer at Tokyo Women's University, but has said that he decided against renouncing his Imperial status in order to promote democracy by identifying at least his share of the clan with the mass of the people. In reply to my invitation, Prince Mikasa said he would be at the hotel main entrance at 7.30, and he was there on the dot. He came alone, and we proceeded to the dining-room, where no special arrangements of any kind had been made. Judging from the ultra deep bows of the head waiter and the startled glances of some of the Japanese diners, I assumed that the Prince's descent into democratic ways of feeding was still having the effect of a social earthquake on many commoners. The Prince ordered steak and a slice of melon for dessert, but merely fiddled with a glass of sherry I had poured he is accurately accused of not drinking or smoking and being astoundingly devoted to his wife and numerous children. Rather rudely, I fear, I began almost immediately to draw the Prince out on aspects of his book, which had not yet been commented upon in the Japanese or foreign language Press. The cables had already picked up his book's more vigorous reflections on how he was compelled to join the Imperial Army, on the deep suspicions his attitude engendered among the militarist hierarchy, on his denunciation of Japan's "Holy War" as "an orgy of pillage, assault, arson, and rape." What I was particularly interested in, however, was the order of precedence he himself gave to his "recollections," and the impact he felt they were having on the readers who were making his book Japan's most controversial best-seller. The Prince answered my questions with complete frankness, even those I predicated as being off the record. China missions There is no doubt of the extent to which Mikasa was moved by the selfless, sacrificing Christian missionaries he met in the remote interior of China during his "holy war" days. This was the type of missionary that toiled on in spite of hard ship and privation, made no political capital out of the persecution it suffered, and left judgment of the sinners to a Higher Being. It was to solve the riddle of these dedicated souls that Mikasa began his study of the origins of Christianity in ancient Oriental history. "What was it that inspired them to such sublime acts of humanity?" Mikasa asked himself, and he sought the answer in the Testaments and the prophets' cry for social justice. The riddle was the more complex in that the allegedly Christian countries from which these true Christians came fervently slaughtered one another in the name of the same Christian God. Another Chinese puzzle which urged Prince Mikasa on to deeper historical studies was the behavior of the Eighth Route Army (the Yenan Communists). He believed it important that the derivation, perverted or not, of their high moral code and discipline should be studied in more precise historical terms and not solely as an exercise in political propaganda. Personal freedom But the most enlightening part of this dinner and talk with Prince Mikasa (we went on for nearly three hours) was his underscoring of the possible danger signs in Japan's progress toward democracy. He expresses his own immense relief at the unprecedently large measure of personal freedom that came with the end of the war, and he uses this comparison to assess trends in Japan. Prince Mikasa believes (and nobody could know better) that the extent of Japanese "democratisation" will be reflected in the kind of home life that his nephew, the Crown Prince, will be allowed to live in the near future. If Prince Akihito, heir to the throne, is gradually hedged in and made to conform with the ancient rites, Japan's popular democracy will also suffer. The proof of Mikasa's deduction was found in the vicious reaction to his book by the old-time militarists. They understood that, until the Imperial Household again became a closed shop, there was little possibility of stifling the democratic nonsense that was threatening the revival of Japan's divine mission. To this degree, Prince Mikasa becomes not only a "dangerous radical" in the eyes of the traditionalists, but also a rallying point for all who see in him a worthwhile Imperial reflection of the Japanese people. The ancients are the more furious in that Prince Mikasa's book has received overwhelming support, the letters for him flooding out the abuse, and demonstrating that Japanese youth will not -- and cannot -- become a party to the conspiratorial Shinto creed of archaic divinities. Patriotic accident As, in the present circumstances, it might be indiscreet to arrange a patriotic accident for Prince Mikasa, the elders are doing the next best thing. The nicest people, cleverly coached without their knowing it, will repeat the fiction that Prince Mikasa is really an eccentric whose head has been turned by too much exotic study of democratic flimflam and Christian superstition. My own impression -- and I went into this meeting with a nastily critical approach -- is that Mikasa's eccentricity has been purely one of a genuine -- and amazing -- breakaway from the most rigidly Imperial routine since the days of the Pharaohs. Foreigners here, especially the diplomats, are observing a rather embarrassed silence in relation to Prince Mikasa and this first blunt documentation of Japanese Imperialism from the inside. One gets the impression that we, too, feel this Imperial Prince has let down the good old side of blue blood, and ordained privilege. This young man (41) certainly has let it down in terms of domestic protocol. At about 10.30 of this memorable evening, Prince Mikasa glanced at his watch and almost leapt from his chair. "Goodness," he said. "I have to pick up my wife at the cinema." AND THEN, AFTER A WARM FAREWELL, HE WAS ON HIS WAY, BUT MORE LIKE AN ORDINARY ANXIOUS HUSBAND THAN AN IMPERIAL DESCENDANT OF JAPAN'S ANCIENT GODS. Japanese Prince Indicts Country's Wartime Record

TOKYO -- (UP) -- For the first time a member of Japans once sacrosanct imperial family plans a public indictment of the "sacred war" Japan waged more than a decade ago and of the pre-war god-emperor system. Prince Mikasa, earnest soul-searching youngest brother of Emperor Hirohito, wrote the bitter denunciation of the pre-war Japanese system in an appendix to a scholarly book on the ancient Orient which he is to bring out soon. In it, the 40-year-old prince attacks the "abominable atrocities" of Japanese troops in China under the masquerade of a sacred war. As an imperial prince, he automatically became a soldier and was assigned to that theater as a staff officer. He also flays the rigid shackles placed on members of the imperial family under the pre-war imperial household system and describes his release from the system after the end of the war as like being liberated from a "prison without bars." Excerpts from the article, recently printed in the newspaper Mainichi, showed the mental torture of a man, himself loving simplicity and the common man, being forced against his will into the career of a soldier and isolated from people by the barriers of an inexorable god-emperor system which extended to all royalty. "When I was a staff officer in Nanking," he wrote, "I lost all faith in the sacred war and wanted only peace. I was disgusted at the actualities of the sacred war. There is no need to bring up here again the abominable atrocities inflicted on the innocent Chinese people. Under the name of a just war violence destruction by fire and rape were being carried on. "I would like to apologize to my subordinates of that time concerning the moral fable of the sacred war." When the war ended Prince Mikasa was torn by conscience and moral pangs and thought seriously about what he himself should do. Many Japanese had been jailed as war criminals. All nobility except immediate relatives of the emperor had been stripped of their rank. He wrote that he thought of renouncing his position as a member of the imperial family and becoming a commoner "but remained because I thought a prince I might be able to do some good." Later the prince began studying Oriental archaeology at Tokyo University. He described his relief at being able to study and talk freely without a frock-coated chamberlain in attendance in the classroom. "I tasted the pleasure of opening an aluminum lunch box and eating salted salmon in the research room," he wrote. The prince, who is now lecturing on Oriental archaeology at a Tokyo University, explained: "The reason I studied Oriental archaeology is that I wanted to seek out from the ruins in the Middle and Near East which was the origin of mankind and culture the outlines of man and the state and think over what man should be." The book in which this article will appear is compiled from a series of radio lectures by the prince and has been tentatively given the title, "Emperors, Graves and People -- The Dawn of The Orient." Prince Mikasa was instrumental in arranging a visit to Mesopotamia by a group of Japanese archaeologists this year and may accompany the expedition himself. From Calvinism in History by McFetridge (1892): And here let it be remarked

that events follow principles; that mind rules the world; that thought

is more powerful than cannon; that "all history is in its inmost nature

religious;" and that, as John von Muller says, "Christ is the key to

the history of the world," and, as Carlyle says, "the spiritual will

always body itself forth in the temporal history of men." In the

formation of the modern nations religion performed a principal part. The great movements out of which the present civilized nations sprung were religious through and through.

What part, then, had Calvinism in begetting and shaping and controlling those movements? What has it to show as the result of its labors? A rich possession indeed. A glorious record be, longs to it in the history of modern civilization. Be it remembered that Luther was an Augustinian or Calvinistic monk, and that it was from this rigorous theology that he learned the great truth, the pivot of the Reformation and the kindling flame of civilization耀alvation, not by works, but by faith alone. True, indeed, that truth was first laid down in the word of God. We can accept as complimentary the sneering remark of Ernest Renan, that Paul begat Augustine, and Augustine begat Calvin, and Calvin begat the Janseniste and their brethren. We glory in the lineal descent. And we stand willing also to acknowledge the kindness of Matthew Arnold, when, in his vain attempts to cut Calvinism out of the New Testament and fling it away, he declares Paul to have been the author of it, but excuses the great apostle for being guilty of it by saying that he allowed himself "to fall into it" through mistake and through the speculative bent of his intellect. But one might be tempted to ask Mr. Arnold, How could Paul have "fallen into it" unless it had been already in existence? And from what ground did the great apostle fall? Truly the Church is in a sad plight if the doctrines of the apostles are the errors which they "fell into "! It is pleasing, however, to some of us to find such men as these attributing the paternity of Calvinism to St. Paul, and to find them driven to such extremities in their efforts to explain it away as to be compelled to say that Paul was mad, or, an an Arminian clergyman of our own city has said, that "Paul was not converted when he wrote the book of Romans." So, then, enemies themselves being witness, Paul, had laid down the grand truth which Luther found in his study of the Augustinian theology and of the Bible. The Arminianism of the Church of Rome had so perverted that truth, and so wrapped it over with its "works of righteousness," as to make it practically unknown. It was not till Luther had grasped it clearly and firmly in his intellect and heart that it became again a living thing and a mighty force. Henceforth the secret power and stirring watchword of the Reformation was justification by faith alone. It was this cleanly-cut and strong theology which began the Reformation, and which carried it on through fire and flood, through all opposition and terror and persecution and misery, to its glorious consummation. When in the great toil and roar of the conflict the fiery nature of Luther began to chill, and he began to temporize with civil rulers, and to settle down in harmony with them, it was this same uncompromising theology of the Genevan school which heroically and triumphantly waged the conflict to the end. I but repeat the testimony of history, friendly and unfriendly to Calvinism, when I say that had it not been for the strong, unflinching, systematic spirit and character of the theology of Calvin, the Reformation would have been lost to the world. That is one thing which Calvinism has done. That is one of the fruits which have grown on this vigorous old tree. Hence it was that almost everywhere the Reformation assumed the Calvinistic type, supplanting or absorbing all other reforming ideas. Even in the lands, such as Germany and Switzerland, where the peculiarly Lutheran ideas had first found acceptance, it was "through the influence of Calvinistic principles that the Protestantism of those lands assumed an external form and organization, and attained to definite dimensions in the history of the world."' In this system only were found that vigor and that earnestness which are essential to the highest success. Even Luther himself, when the splendor of Calvin's name was outshining his own, withheld not his admiration and praise from the strict discipline which prevailed in the Calvinistic churches, and from that lofty earnestness which pervades the whole Calvinistic system of reform, and which gave it more and more of that steady consistency that was requisite in its conflict with opposing powers, and without which no victory is ever attained. "The Lutheran congregations were but half emancipated from superstition, and shrank from pressing the struggle to extremities; and half measures meant half-heartedness, convictions which were but half convictions, and truth with an alloy of falsehood. Half measures, however, would not quench the bonfires of Philip of Spain or raise men in France or Scotland who would meet crest to crest the princes of the house of Lorraine. The Reformers required a position more sharply defined and a sterner leader, and that leader they found in John Calvin... For hard times hard men are needed, and intellects which can pierce to the roots where truth and lies part company. It fares ill with the soldiers of religion when 'the accursed thing' is in the camp. And this is to be said of Calvin, that, so far as the state of knowledge permitted, no eye could have detected more keenly the unsound spots in the creed of the Church, nor was there a Reformer in Europe so resolute to exercise, tear out and destroy what was distinctly seen to be false -- so resolute to establish what was true in its place, and make truth, to the last fibre of it, the rule of practical life." This is the testimony of a man who has no particular love for Calvinism, but who from the high ground of learned investigation looks at it and the man whose name it bears through the light of historical fact. And in further explication of this thought allow me to quote again from the same authority: "Was it not written long ago, 'He that will save his soul shall lose it'? If we think of religion only as a means of escaping what we call the wrath to come, we shall not escape it; we are already under it; we are under the burden of death, for we care only for ourselves. This was not the religion of your fathers; this was not the Calvinism which overthrew spiritual wickedness, and hurled kings from their thrones, and purged England and Scotland, for a time at least, of lies and charlatanry. Calvinism was the spirit which rises in revolt against untruth -- the spirit which, as I have shown you, has appeared and reappeared, and in due time will appear again unless God be a delusion and man be as the beasts that perish. For it is but the flashing upon the conscience of the nature and origin of the laws by which mankind are governed, laws which exist whether we acknowledge them or whether we deny them, and will have their way, to our own weal or woe, according to the attitude in which we place ourselves toward them -- inherent, like the laws of gravity, in the nature of things; not made by us, not to be altered by us, but to be discerned and obeyed by us at our everlasting peril.'" This was the Calvinism which flashed forth in the great Reforming days -- the spirit which, when Romanists and despots claimed the right to burn all who differed from them, inspired men and women and youth to go forth, Bible and sword in hand, to the greatest daring, appealing for the justice of their cause and the victory of their arms to the Lord of hosts. This was the spirit which acted in those men "who attracted to their ranks almost every man in Western Europe who hated a lie;" who when they were crushed down rose again; who "abhorred as no body of men ever more abhorred all conscious mendacity, all impurity, all moral wrong of every kind, so far as they could recognize it;" who, though they did not utterly destroy Romanism, "drew its fangs, and forced it to abandon that detestable principle that it was entitled to murder those who dissented from it." This was the spirit out of which came, and by which was nourished, the religious and civil liberties of Christendom; of which Bancroft says, "More truly benevolent to the human race than Solon, more self-denying than Lycurgus, the genius of Calvin infused enduring elements into the institutions of Geneva, and made it for the modern world the impregnable fortress of popular liberty, the fertile seed-plot of democracy." That religious and civil liberty have an organic connection and a natural affinity is quite obvious. They hold together as root and branch. "By the side of every religion is to be found a political opinion connected with it by affinity. If the human mind be left to follow its own bent, it will regulate the temporal and spiritual institutions of society in a uniform manner, and man will endeavor, if I may so speak, to harmonize earth with heaven." But other influences may be powerful enough to interfere with this natural connection of the religious and political belief. The Romanist may choose to be a republican rather than a monarchist, because of the greater advantages which a republic confers, or because he finds himself in the midst of republican institutions which he cannot hope to alter; but when a man is free to follow his own inclinations, he will body forth his religion in his political beliefs. Hence it comes that the influence on our republican institutions of a rigid Arminianism, which has always been wedded to an aristocratic form of church government, is unfavorable to their perpetuity. Its whole tendency, politically, is to educate the sentiments of the people to a spirit of subjection to the rich and powerful, and thus to prepare them for the monarchic form of civil government. Charles I of England gave as the reason why his father, James I, had subverted the republican form of government of the Scottish Church, that the presbyterial and monarchical forms of government do not harmonize. And De Tocqueville, admitting the same, calls Calvinism "a democratic and republican religion." This is the historical fact, that, while Calvinism can live and do its divine work under any form of civil government, its natural affinities are not with a monarchy, but with a republic. This is the reason that it has made so splendid a record in the history of human freedom. Where it flourishes despotism cannot abide. This, says the historian D'Aubigne, "chiefly distinguishes the Reformation of Calvin from that of Luther, that wherever it was established it brought with it not only truth, but liberty, and all the great developments which these two fertile principles carry with them." Now, if we ask what Calvinism did for the cause of civil and religious liberty in France and the Netherlands, we have but to turn to the glowing pages of D'Aubigne and to the enchanting histories of our own Motley. It created, under God, the Dutch Republic, and made it "the first free nation to put a girdle of empire around the world." Account for it as one will, the fact is, that until Calvinism took possession of the Netherlanders and gained the ascendency over all other religious beliefs, the people made but little headway against the powerful empire of Spain; but from that moment they never faltered for wellnigh a hundred years, until their independence was triumphantly established. Their great leader, William the Silent, prince of Orange, was, as it would appear, forced logically, consistently and necessarily to give up first his Romanism and next his Lutheranism, and to become a sincere and rigid Calvinist while fighting for his country's independence. Then it was that he began to exhibit such vigor and enthusiasm and perseverance as he had never before exhibited. Then it was that he began to make those bleak fields of the North to be the light and hope of the Protestant world and the terror of the proud and powerful Philip of Spain. "It would certainly be unjust and futile," says Motley, "to detract from the vast debt which that republic owed to the Genevan Church. The Reformation had entered the Netherlands by the Walloon gate (that is, through the Calvinists). The earliest and most eloquent preachers, the most impassioned converts, the sublimest martyrs, had lived, preached, fought, suffered and died with the precepts of Calvin in their hearts. The fire which had consumed the last vestige of royal and sacerdotal despotism throughout the independent republic had been lighted by the hands of Calvinists. "Throughout the blood-stained soil of France, too, the men who were fighting the same great battle as were the Netherlanders against Philip II and the Inquisition, the valiant cavaliers of Dauphiny and Provence, knelt on the ground before the battle, smote their iron breasts with their mailed hands, uttered a Calvinistic prayer, sang a psalm of Marot, and then charged upon Guise or upon Joycuse under the white plume of the Bearnese. And it was on the Calvinistic weavers and clothiers of Rochelle that the Great Prince relied in the hour of danger, as much as on his mounted chivalry. In England, too, the seeds of liberty, wrapped up in Calvinism and hoarded through many trying years, were at last destined to float over land and sea, and to bear largest harvests of temperate freedom for great commonwealths that were still unborn." To the Calvinists, "more than to any other class of men, the political liberties of Holland, England and America are due." Such language might be mistaken for a mere panegyric of an intense Calvinist, did we not know that it is the historical testimony of one who was not a Calvinist, but who, with the fire of freedom burning brightly in his heart, and with a perfect knowledge of what he is saying, pays such lofty tributes to the men who dared maintain the cause of liberty in the earth. This is sufficient to indicate, as I here can only do, what was the influence and what the worth of Calvinism on the liberties of France and the Netherlands. See also Calvinism and the Home by McFetridge. Thomas Bradwardine is a name probably no one recognizes today, yet he was one of those amazing heroes of the faith and one of the forerunners of the Reformation. From the History of the Christian Church, Volume 2, by John Fletcher Hurst (1900): Another man whom Wyclif

greatly loved was Thomas Bradwardine, mathematician and theologian,

teacher of theology at Oxford, chancellor of St. Paul's in London,

chaplain to Edward III during his war with France, 1339, and for a few

weeks only archbishop of Canterbury. He died prematurely of the plague

on August 26, 1349. Bradwardine was one of those earnest scholars and

spiritual men whom the Church in England has reared, a man who, like

Isaac Barrow, was equally great as a mathematician and as a theologian.

He did not consciously deviate from the teaching of the Church, and he

submits all his opinions to her authority; but in his profoundly Augustinian mind, his emphasis on grace, his earnest protests against any trace of Pelagianism, and the spiritual fervor of his writings he plowed the soil deep for Wyclif's sowing.

In a most interesting passage Bradwardine gives an account of his awakening to the evangelical conception of grace: "I was at one time, while

still a student of philosophy, a vain fool, far from the true knowledge

of God, and held captive to opposing error. From time to time I heard

theologians treating the questions of grace and free will, and the

party of Pelagius appeared to me to have the best of the argument. For

I rarely heard anything said of grace in the lectures of the

philosophers except in an ambiguous sense; but every day I heard them

teach that we are masters of our own free acts, and that it stands in

our own power to do either good or evil, to be either virtuous or

vicious, and such like. And when I heard now and then in church a

passage read from the apostle which exalted grace and humbled free will

-- such, for example, as that word in Rom. ix, 'So then it is not in

him that willeth, nor in him that runneth, but in God that showeth

mercy,' and other like places -- I had no liking for such teaching, for

toward grace I was still unthankful. I believed also, with the

Manichaeans, that the apostle, being a man, might possibly err from the

truth on any point of doctrine. But afterward, and before I had become

a student of theology, the truth struck upon me like a beam of grace,

and it seemed to me as if I beheld in the distance, under a transparent

image of truth, the grace of God as it is, prevenient both in time and

nature to all good deeds, that is to say, the gracious will of God

which precedently wills that he who merits salvation shall be saved,

and precedently works this merit of it in him, God in truth being in

all movements the primary mover. Wherefore, also, I give thanks to him

who has freely given me this grace."

Bradwardine felt himself called to oppose the superficial views then prevalent in the Church. "The doctrine is held by many," he says, "that either the free will of man is of itself sufficient for the obtaining of salvation, or if they confess the need of grace, that still grace may be merited by the power of the free will, so that grace no longer appears to be something undeserved by men, but something meritoriously acquired. Almost the whole world has run after Pelagius and fallen into error." Bradwardine's treatise "Of the Cause of God" is an able and earnest exposition of the Pauline doctrine, according to the thought of St. Augustine, whom the author highly praises, and an appeal to the Church to return to the old paths. Although Bradwardine did not have the genius of Wyclif in the latter's breadth and boldness of theological reconstruction, he yet prepared the way for him by his thoroughly Protestant doctrine of grace. Let us say here that Bradwardine's doctrine, resting firmly on the scriptural principle that every good and perfect gift cometh down from the Father of lights, needed only the modification of the other truth, that in the reception and use of those gifts the sinner is left absolutely free. The movements toward salvation which he feels are from God alone, but he is yet master of himself in the response which he chooses to make to the divine promptings. |

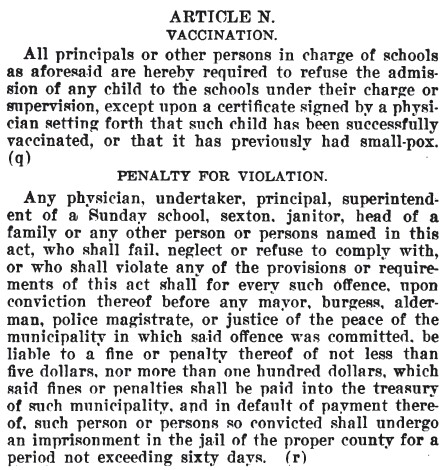

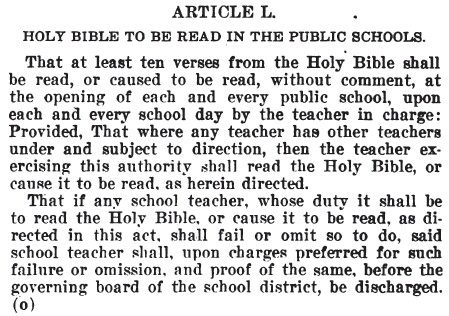

Pennsylvania School Law of 1915 requiring smallpox vaccinations:

...and Bible reading:

- Infant Baptism

- Original Sin

- Freewill

- Grace

- Predestination and Redemption

Evangelical News in Asia, 1882

"The Jesus Religion" growing in Japan

Japanese Buddhists alarmed at spread of Christianity

Japanese custom of killing newborn babies

Korea opened to the Gospel

Moral and religious element almost totally ignored

|

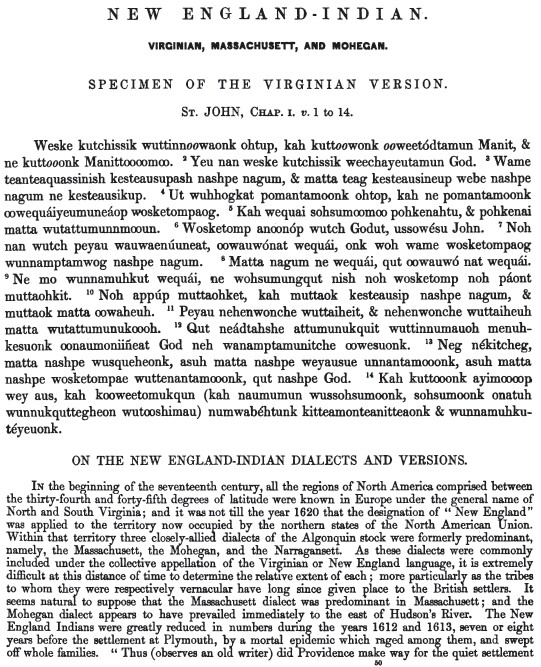

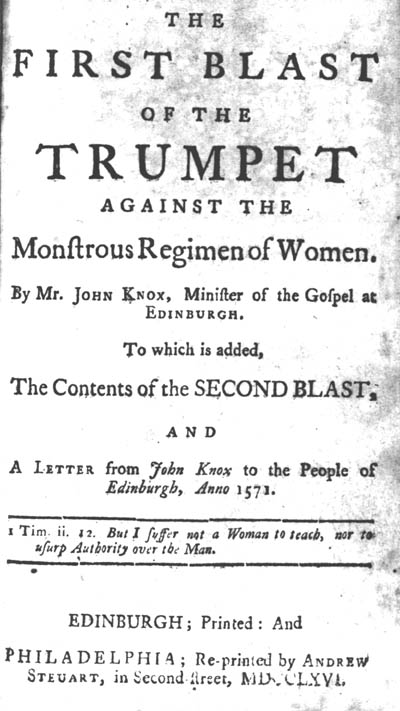

First translation of the New Testament by missionary John Eliot

into the language of the native tribes of New England in 1661

(from Bagster's The Bible of Every Land, 1848)

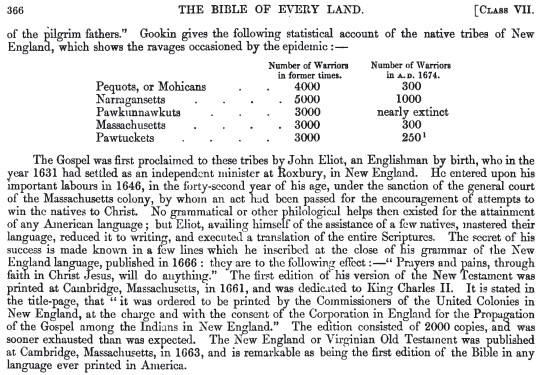

The Lord's Prayer in Chinese, regular and grass writing (Bagster 1848)

Recipe for Christmas mince pies

and

New Year's Day

(from Sandys Christmas Carols, Ancient and Modern, 1833)

"the weak members of civilised societies propagate their kind"

Excerpt from Charles Darwin's

The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1874)

With savages, the weak in body or

mind are soon eliminated; and those that survive commonly exhibit a

vigorous state of health. We civilised men, on the other hand, do our

utmost to check the process of elimination; we build asylums for the

imbecile, the maimed, and the sick; we institute poor-laws; and our

medical men exert their utmost skill to save the life of every one to

the last moment. There is reason to believe that vaccination has

preserved thousands, who from a weak constitution would formerly have

succumbed to small-pox. Thus the weak members of civilised societies

propagate their kind. No one who has attended to the breeding of

domestic animals will doubt that this must be highly injurious to the

race of man. It is surprising how soon a want of care, or care wrongly

directed, leads to the degeneration of a domestic race; but excepting

in the case of man himself, hardly any one is so ignorant as to allow

his worst animals to breed.

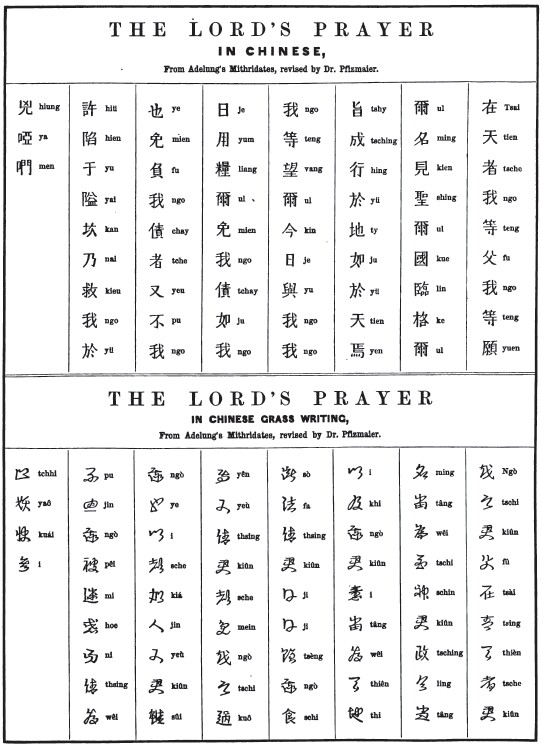

Quite a title for a book "against the monstrous regimen of women"!

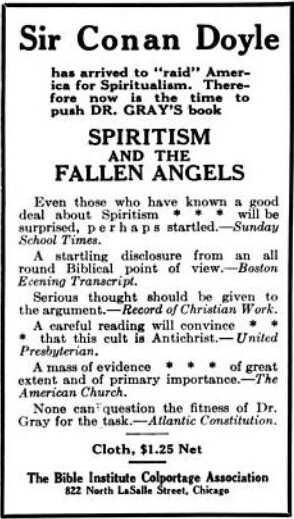

Famous author and Jesuit Sir Arthur Conan Doyle --

a warning regarding his spiritism

October 13, 2025

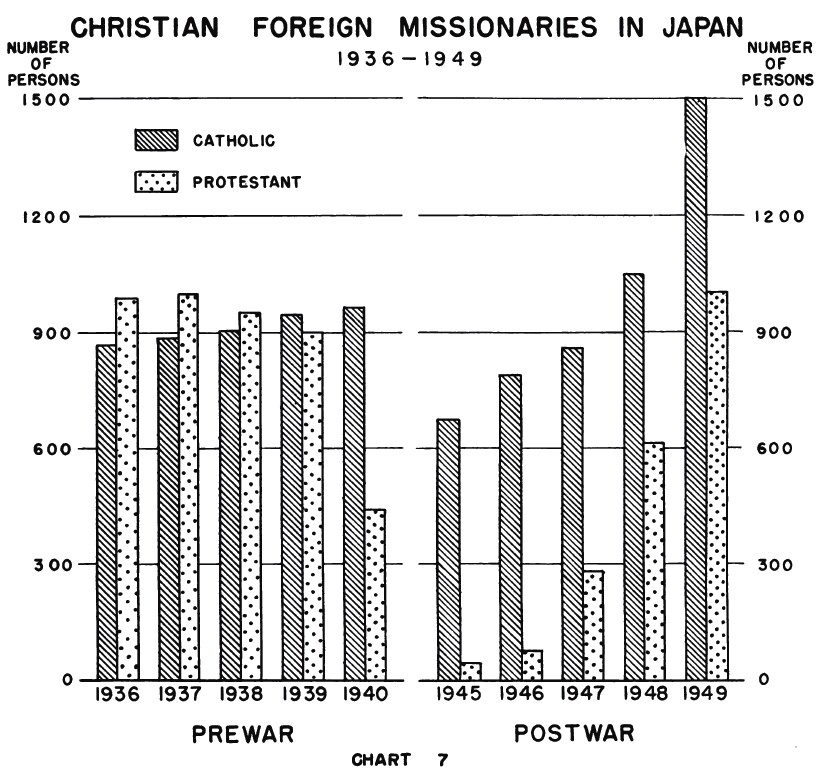

Foreign Missionaries in Japan 1936-1949

(Selected Data on the Occupation of Japan)

The above graph shows a very interesting development a few years prior to the outset of the Pacific War -- Why the sudden decrease of Protestant missionaries, whereas Roman Catholics saw but a 30% drop? True, this is due to the expelling or interning of Allied-nation missionaries after the Pearl Harbor attack, but were they all only Protestants? A further study would be needed to determine if the Roman Catholics were primarily from the Axis nations of Germany, Italy and France. Also interesting is the slow post-war Protestant response to MacArthur's request for more missionaries to Japan.

September 13, 2025

What exactly has Christianity done for Japan?

As I have tried to show through the work of some amazing missionaries

to Japan (see Foreigners Who Changed Japan series), Japan owes an

immense amount of gratitude to those men and women who, by God's grace,

helped to bring Japan out of the darkness of idolatry to become a part

of those nations who recognize the true God. Here's from the

Introduction to M.L. Gordon's, An American Missionary in Japan (1892); read this chapter entitled, "Christianity and New Japan."By his direct, manly, and

outspoken story of missionary life in Japan, Dr. Gordon has made a

contribution to the literature both of knowledge and of power. The

information here furnished is copious, genuine, and at first hand,

while to the stimulus of mind and heart which the work affords the

writer of this note gladly testifies. Familiar with the modern library

of books on Japan, both of the standard and ephemeral sort, he ventures

the prophecy that this fruit of the pen is no Jonah's gourd. Nor is it

the report of a frightened spy brought back from a land of promise; it

is rather the courageous asseveration of a true soldier who, in the

name of the Great Captain, says of the land in view, "We are well able

to possess it." Having seen and weighed difficulties, he summons us to

the front, not to the rear; to the charge, not to the retreat.

The people want facts, not cant or fancies. Dullness in telling the missionary story should be branded as a sin. The public will always give heed to the man who tells what he saw, not what he went out to see. Japan is not a reed shaken by the wind; not an Oriental merry-andrew, or an odalisque clothed in soft raiment to amuse the sensual tourist or writer; not a false prophet whose gospel is novelty and revolution. A nation has been born, seemingly in a day, but in reality only after long travail of prison-pain, civil war, and agony of spirit. Struggling in newness of life toward a lofty ideal undreamed of even by the men of the Revolution of 1868, Japan is yet to be, under Divine Providence, God's messenger to all Asia. Amid the crowd of books written by modern Pharisees, bigoted and narrow-minded; by Sadducean lovers of lust, who want Japan kept pagan, aesthetic, and morally cheap; by hasty scribblers of vapid trash, -- it is refreshing to meet with the literary work of a liberal Christian, who has been servant and fellow-worker with the serious men and women of New Japan. He sees the truth and tells it.

The writer of this note was not a "missionary," in the technical sense, but was in the educational service of the Japanese government. All the more, from his close personal acquaintance with native princes, statesmen, and the young men who are now prominent in political life, had he opportunity to know of the noble work done by the American missionaries in the development of the nation. Such names as those of Brown, Hepburn, Verbeck, and Greene, are not only household words in New Japan, but, were it not the violation of private confidence, the writer could show how, in grave crises of state, their advice was sought and followed. Dr. S. R. Brown trained some of the very first of the young statesmen of New Japan. Dr. J. C. Hepburn has healed tens of thousands of her people. Of the Imperial Embassy that made the circuit of the globe and of Christendom in 1872, one half had been Dr. Verbeck's pupils. It seems more like miracle than history to tell that, in Kyōto, where Yokoi Héishiro was in 1868 assassinated for entertaining Christian convictions, there now stand Neesima's Dōshisha University and many Christian churches; while in Tōkyō, the son of Yokoi preaches the gospel, both as pastor and editor. To find in the first Imperial Diet of constitutional Japan no fewer than fifteen pronounced Christian men, is but to tell, in another way, what God hath wrought through the American missionaries.

For these men have, apart from their holy calling, done a mighty work in the making of New Japan. Not less than Matthew Perry and Townsend Harris, have they incarnated the United States as the Great Pacific Power. They have, by the education of their Japanese fellow-believers in self- support, in parliamentary training, at church-meetings and in ecclesiastical conventions, taught them the arts of self-government. They have helped mightily to prepare the nation for the responsibilities of freedom and the duties of constitutional politics. They have aided Sovereign and Government to maintain social order in a trying epoch, when the old moulds of traditions had been broken, and the ideals and sanctions of ages of feudalism were passing away. When the need was sorest, they brought the priceless boon of Christian ethics. They taught and illustrated Christian civilization while preaching Christ's salvation.

Yes, grateful must all be, who love Christ more than tradition, that true servants of His, like the author, have so faithfully preached the good news of God. It is Christ's salvation, rather than the particular Yankee, or British, or other temporary form of it, which they have declared. "And to each seed a body of its own," has been their rule, after the apostolical model. They have let the Japanese shape their own theology. When most the servants, they have been consummate masters. Largely through them, it may be, that, under Divine Providence, Christian Japan has yet much to teach us of "the simplicity that is in Christ."

As now the author's enforced absence ends, and he turns his face towards the sunset (yet also towards Rising Sun Land), to take up his work in Kyōto, we wish him Godspeed. May he and all the American missionaries in Japan so turn many to righteousness that when they rest from their labors their works may follow them.

The people want facts, not cant or fancies. Dullness in telling the missionary story should be branded as a sin. The public will always give heed to the man who tells what he saw, not what he went out to see. Japan is not a reed shaken by the wind; not an Oriental merry-andrew, or an odalisque clothed in soft raiment to amuse the sensual tourist or writer; not a false prophet whose gospel is novelty and revolution. A nation has been born, seemingly in a day, but in reality only after long travail of prison-pain, civil war, and agony of spirit. Struggling in newness of life toward a lofty ideal undreamed of even by the men of the Revolution of 1868, Japan is yet to be, under Divine Providence, God's messenger to all Asia. Amid the crowd of books written by modern Pharisees, bigoted and narrow-minded; by Sadducean lovers of lust, who want Japan kept pagan, aesthetic, and morally cheap; by hasty scribblers of vapid trash, -- it is refreshing to meet with the literary work of a liberal Christian, who has been servant and fellow-worker with the serious men and women of New Japan. He sees the truth and tells it.

The writer of this note was not a "missionary," in the technical sense, but was in the educational service of the Japanese government. All the more, from his close personal acquaintance with native princes, statesmen, and the young men who are now prominent in political life, had he opportunity to know of the noble work done by the American missionaries in the development of the nation. Such names as those of Brown, Hepburn, Verbeck, and Greene, are not only household words in New Japan, but, were it not the violation of private confidence, the writer could show how, in grave crises of state, their advice was sought and followed. Dr. S. R. Brown trained some of the very first of the young statesmen of New Japan. Dr. J. C. Hepburn has healed tens of thousands of her people. Of the Imperial Embassy that made the circuit of the globe and of Christendom in 1872, one half had been Dr. Verbeck's pupils. It seems more like miracle than history to tell that, in Kyōto, where Yokoi Héishiro was in 1868 assassinated for entertaining Christian convictions, there now stand Neesima's Dōshisha University and many Christian churches; while in Tōkyō, the son of Yokoi preaches the gospel, both as pastor and editor. To find in the first Imperial Diet of constitutional Japan no fewer than fifteen pronounced Christian men, is but to tell, in another way, what God hath wrought through the American missionaries.

For these men have, apart from their holy calling, done a mighty work in the making of New Japan. Not less than Matthew Perry and Townsend Harris, have they incarnated the United States as the Great Pacific Power. They have, by the education of their Japanese fellow-believers in self- support, in parliamentary training, at church-meetings and in ecclesiastical conventions, taught them the arts of self-government. They have helped mightily to prepare the nation for the responsibilities of freedom and the duties of constitutional politics. They have aided Sovereign and Government to maintain social order in a trying epoch, when the old moulds of traditions had been broken, and the ideals and sanctions of ages of feudalism were passing away. When the need was sorest, they brought the priceless boon of Christian ethics. They taught and illustrated Christian civilization while preaching Christ's salvation.

Yes, grateful must all be, who love Christ more than tradition, that true servants of His, like the author, have so faithfully preached the good news of God. It is Christ's salvation, rather than the particular Yankee, or British, or other temporary form of it, which they have declared. "And to each seed a body of its own," has been their rule, after the apostolical model. They have let the Japanese shape their own theology. When most the servants, they have been consummate masters. Largely through them, it may be, that, under Divine Providence, Christian Japan has yet much to teach us of "the simplicity that is in Christ."

As now the author's enforced absence ends, and he turns his face towards the sunset (yet also towards Rising Sun Land), to take up his work in Kyōto, we wish him Godspeed. May he and all the American missionaries in Japan so turn many to righteousness that when they rest from their labors their works may follow them.

WM. ELLIOT GRIFFIS

BOSTON: SHAWMUT CHURCH

September 22, 1892

BOSTON: SHAWMUT CHURCH

September 22, 1892

September 6, 2025

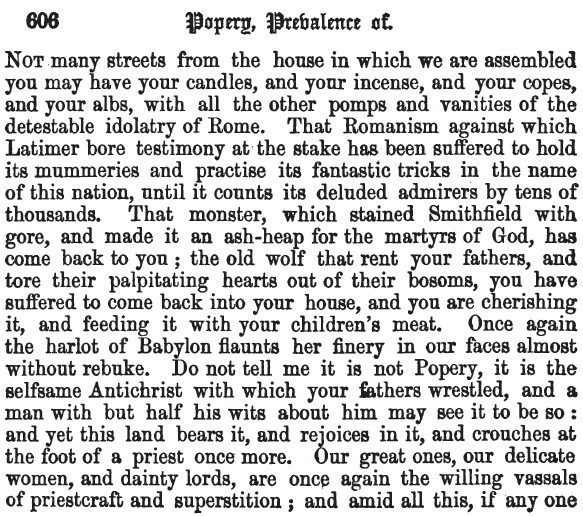

Romish Priestcraft Dishonouring

to God

and

Prevalence of Popery

ALAS! alas! It makes a Christian's blood boil to see glory given in a

professed place of worship, ay, and in a professed Protestant church,

too, to a pack of scamps who call themselves "priests"! I would not

call them by such a name if they were honest enough to go off to the

Church of Rome, where they ought to be; but having the impudent

effrontery to attempt to palm themselves off in this country of ours

for what they are not, I know of no words bad enough for them.What reverence or respect is to be paid to those gentry inside those brass gates, around the thing they call an altar? I suppose those gates enclose a sort of holy place, into which the poor laity must not go! If these priests had their way, we should have to go down and lick the soles of their feet, as our benighted forefathers aforetimes bowed before the hirelings of Rome. Does it not make a man feel, when you see pictures of his holiness and the cardinals, and so on, scattering their benedictions at the Vatican, or at St. Peter's, while admiring crowds fall down and worship them, that it were infinitely better to bow to the devil himself? We give glory unto God, but not a particle of glory to anything in the shape of a man, or an angel either.

Have I not stood and seen the crowds by hundreds fall down and worship images and dressed-up dolls? I have seen them worship bones and old teeth; I have seen them worship a skeleton, dressed out in modern costume, said to be the skeleton of a saint; and I have marvelled how we could, in this nineteenth century, find people so infatuated as to think that such idolatry was pleasing to the most high God. We, brethren, the people of God, who know Christ, can give no glory to this rubbish, but turn away from it with horror. Our glory must be given to Christ, and to Christ alone.

Now, here is the touchstone to try your religion by. When you pray, to whom do you pray? Through whom do you pray? When you sing, for whom is the song meant? When you preach, to whose honour do you preach? To whom do you intend to do service? When you go out among the poor, when you distribute alms, when you scatter your tracts, when you talk about the gospel, for whom do you do this? For, as the Lord liveth, if you do it for yourselves, or for any beside the Lord Jesus, you do not know what the vitality of godliness is, for Christ, and Christ only, must be the grand object of the Christian: the promotion of his glory must be that for which he is willing to live, and for which, if needs be, he would be prepared to die.

Oh! down, down, down with everything else, but up, up, up with the cross of Christ! Down with your baptism, and your masses, and your sacraments! Down with your priestcraft, and your rituals, and your liturgies! Down with your fine music, and your pomp, and your robes, and your garments, and all your ceremonials. But up, up, up with the doctrine of the naked cross, and the expiring Saviour. Let the voice ring throughout the whole world. "Look unto me and live!" There is life in a look at the crucified One. There is life in simple confidence in him, but there is life nowhere else. God send to his church an undying passion to promote the Saviour's glory, an invincible, unconquerable pang of desire, and longing that by any means King Jesus may have his own, and may reign throughout these realms! In this sense, then, Jesus is and must be the glory of his people.

From: A Flashes of Thought! Being One Thousand Choice Extracts from the Works of Charles Spurgeon (1874)

May 9, 2025

Advice to Missionaries

David Brainerd was one of most influential missionaries that ever lived. William Carey, called "the father of modern missions" and who himself was a missionary to India, regarded the Life of Brainerd the most important book next to the Bible. He once wrote in his journal, "I was much humbled today by reading Brainerd. O what a disparity betwixt me and him! He always constant, I as inconstant as the wind!"Here is an excerpt from Brainerd's own journal where he gives advice on what to preach and teach, some very good advice for missionaries. Also included is a short section with more excellent advice by missionary to Burma, Adoniram Judson.

FIRST APPENDIX

TO MR. BRAINERD’S JOURNAL:

CONTAINING HIS GENERAL REMARKS ON THE DOCTRINES PREACHED,

THEIR EXTRAORDINARY EFFECTS, &c. (June 20, 1746)

and

ADVICE TO MISSIONARY CANDIDATES

By Adoniram Judson

To the Foreign Missionary Association

of the Hamilton Literary and Theological Institution, N. Y.

Maulkain, June 25, 1832.

CONTAINING HIS GENERAL REMARKS ON THE DOCTRINES PREACHED,

THEIR EXTRAORDINARY EFFECTS, &c. (June 20, 1746)

and

ADVICE TO MISSIONARY CANDIDATES

By Adoniram Judson

To the Foreign Missionary Association

of the Hamilton Literary and Theological Institution, N. Y.

Maulkain, June 25, 1832.

Here is a collection of excerpts from books dealing with the United States and its heritage, and a couple re our constitutional rights:

From The Sabbath by

Kingsbury (1840):

From Commentary on the Constitution by King (1871):

From Commentary on the Constitution by King (1871):

From Commentaries on the Constitution of the US (1833):

April 15, 2025

A Model Marriage - Happy woman and happy man!

SOMETIMES we have seen a model marriage, founded in pure love and cemented in mutual esteem. Therein the husband acts as a tender head, and the wife, as a true spouse, realizes the model marriage relation, and sets forth what our oneness with the Lord ought to be. She delights in her husband, in his person, his character, his affection; to her he is not only the chief and foremost of mankind, but in her eyes he is all in all, her heart's love belongs to him and to him only. She finds sweetest content and solace in his company, his fellowship, his fondness; he is her little world, her paradise, her choice treasure.To please him she would gladly lay aside her own pleasure to find it doubled in gratifying him. She is glad to sink her individuality in his. She seeks no name for herself, his honor is reflected upon her, and she rejoices in it. She would defend his name with her dying breath, safe enough is he where she can speak for him. The domestic circle is her kingdom; that she may there create happiness and comfort is her life-work, and his smiling gratitude is all the reward she seeks. Even in her dress she thinks of him, without constraint she consults his taste, and thinks nothing beautiful which is obnoxious to his eye. A tear from his eye, because of any unkindness on her part, would grievously torment her. She asks not how her behavior may please a stranger, or how another's judgment may be satisfied with her behavior; let her beloved be content and she is glad.

He has many objects in life, some of which she does not quite understand, but she believes in them all, and anything that she can do to promote them she delights to perform. He lavishes love on her and she on him. Their object in life is common. There are points where their affections so intimately unite that none could tell which is first and which is second. To see their children growing up in health and strength, to see them holding posts of usefulness and honor, is their mutual concern; in this and other matters they are fully one. Their wishes blend, their hearts are indivisible. By degrees they come very much to think the same thoughts. Intimate association creates conformity; we have known this to become so complete that at the same moment the same utterance has leaped to both their lips.

Happy woman and happy man! If Heaven be found on earth, they have it! At last the two are so welded, so engrafted on one stem, that their old age presents a lovely attachment, a common sympathy, by which its infirmities are greatly alleviated, and its burdens are transformed into fresh bonds of love. So happy a union of will, sentiment, thought, and heart exists between them, that the two streams of their life have washed away the dividing bank, and run on as one broad current of united existence until their common joy falls into the main ocean of felicity.

From: A Flashes of Thought!

Being One Thousand Choice

Extracts from the Works of Charles Spurgeon (1874)

Extracts from the Works of Charles Spurgeon (1874)

The wondrous spectacle of Christ, the Lamb of God

From: A Commentary upon the

Holy Bible,

from Henry and Scott

(1833)

March 14, 2025

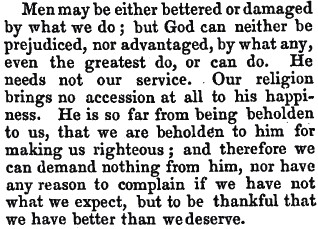

God is not beholden to us, but we

to Him

From: A Commentary upon the

Holy Bible,

from Henry and Scott

(1833)