|

Ten Escape From Tojo By Cmdr. McCoy and Lt. Col. Mellnik The original account of ten POWs who escaped from Davao Penal Colony in the Philippines (original cir. Sept. 1943; published in book form, March 1944) |

| Main | Camp Lists | About Us |

Source: Franklin D.

Roosevelt Library & Museum (http://docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/psf/box3/a37o01.html)

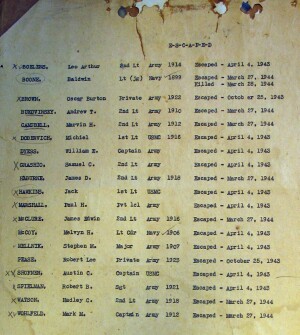

TEN ESCAPE FROM TOJOByCommander Melvin H. McCoy, USN, andLieutenant Colonel S.M. Mellnik, USAas told toLieutenant Welbourn Kelley, USNRCHAPTER ONE "Defeat in the Philippines" In war, casualties are expected. Some men are killed outright. Others are wounded but recover. Still others lose an arm, a leg, or are mutilated in other ways, and they bear the scars or pains of this mutilation for the rest of their lives. These grim consequences of war are accepted as a part of war's grim custom and tradition. It is also a custom and tradition of war that, when men fight honorably and are forced to lay down their arms in sure render, the war for them has reached an end. As helpless prisoners of war, such men do not expect to be pampered. They do expect enough food, shelter, clothing and medical care to keep them alive. They do expect reasonably humane treatment from their captors, and they do expect their captors to treat them as human beings. These things they expect under the comity of nations which decrees that there can be honor even among peoples which are at war. For the 65,000 men who were overpowered and forced to lower the American flag on Bataan and Corregidor, in the Philippines, the enemy provided new rules. Or, rather, those rules of humanity which had been built up in the past were completely ignored or deliberately forgotten. We are two of the Americans who were captured by the Japanese in the fall of Corregidor. With eight others, we were the first to escape from a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp in the Philippines. Before the last organized American resistance was crushed by overwhelming force, we had become accustomed to seeing our comrades die in battle by the score and by the hundreds. Hardship, bloodshed and death were a commonplace. Yet actual war brought nothing like the horror we were to see and experience in eleven months as military prisoners of a nation which had heretofore demanded and received rank on an equal footing with the leading powers of a civilized world. There was little choice for the ten of us who finally escaped from the Japanese. We knew that if we were caught in the attempt we would be put to death in a manner not pleasant to think about -- we had seen it happen to others of our fellow American prisoners. But although our group contained ten of the strongest and healthiest Americans in the prison camp, we knew that there was a better than even chance of death as a result of our captors' treatment if we remained in the prison. We had also seen this happen to others of our fellow prisoners. And when we finally did win our way to freedom -- ten Americans from Bataan and Corregidor-we were aided and accompanied by two Filipino convicts, who in civil life, before the war, had been sentenced for murder, yet were willing to risk death from the Japanese in unselfish loyalty to the United States and their native land. During the eleven months of our captivity the ten of us were to see thousands of Americans die from the willful neglect of our captors -- up to the end of 1945 the Japanese military prisoner-of-war authorities had announced loss than a third of the Americans then dead. More have died since, and it is our considered belief that not more than ten per cent of the American military prisoners in the Philippines will survive another year of the conditions which existed at the time of our escape. During our eleven months of captivity we were to see American officers and enlisted men driven to such as the cleaning of Japanese latrines and sewage systems -- each of us was forced to do both. We were to see American prisoners slapped and beaten without provocation as a commonplace occurrence, and most of us were the helpless personal recipients of such treatment. We were to see Americans so crazed by thirst that they were forced to drink from muddy and polluted carabao wallows, although separated from the clean water of a running stream only by the menace of Japanese bayonets. We were to see Americans by the hundreds suffering in various declining stages of scurvy, malaria, beri beri and other afflictions, because the Japanese would not give us our medications, which they had confiscated; neither would the Japanese permit us to use the fruits and vegetables which grew in profusion around our prison stockades. We were to see Americans slowly going blind from vitamin deficiency; and not one of us escaped without having suffered from one or more of the diseases and deficiencies which at one time were causing the deaths of more than 50 Americans each day. We were to see unconscious Americans, exhausted on the march, tossed into shallow graves and buried while still alive. We were to see our fellow American prisoners drop by the score from dysentery and malnutrition, and their bodies litter our prison camps while waiting for the Japanese to get around to giving us permission to bury our dead. More than a thousand had died before the Japanese permitted us to hold religious services over their bodies or to mark their graves. We were to see Americans tied up and tortured in full view of our prison camp, beaten and battered until they were no longer recognizable as human, before they were finally removed for execution without trial. We were to see and experience a daily pattern of existence and treatment which will remain with us as nightmares and revolting memories for the rest of our lives. Among the ten of us, these nightmares and memories resolve themselves into one simple conviction: Japan as a military power must be utterly and finally defeated, soon. As professional military men -- one a graduate of Annapolis, the other of West Point -- we are fully aware that atrocity stories, as such, can be dangerous in wartime. Yet we feel most emphatically that this story should be told. We feel that all our people should be given a clearer picture of the enemy we face in the Pacific. Most important of all, we feel that the Japanese treatment of American military prisoners, at least in the Philippines, should become a matter of record, now, with the hope that this treatment will be improved if the Japanese ever expect to be viewed on a basis of moral equality with civilized peoples. Finally, we feel that the very highest authorities in Japan should be warned before all the world -- and warned now, so that there can be no evasion of responsibility -- that we are fully aware of Japanese treatment of captured Americans in the Philippine military prisons. In addition, this story is being told -- and an unpleasant story it is -- with the fervent hope that it will increase by even a small particle the American people's feeling of urgency and necessity for a supreme effort in the Pacific, an effort which must not be allowed to diminish until the complete goal has been reached. Although this report has been prepared as a personal narrative by the senior Army and Navy members of the escape party, we cannot emphasize too strongly that no one person deserves mention above any other. Of the other eight, each lived up to the highest traditions of his individual service. Included in the party were Lieutenant Commander (now Commander) Melvin H. McCoy, USN, Annapolis '27; Major (now Lieutenant Colonel) Stephen S. Mellnik, Coast Artillery, West Point '32; three Air Corps officers, Captain W. E. Dyess and Second Lieutenants L. A. Boelens and Samuel Grashio; three Marine Corps officers, Captain A. C. Shofner and First Lieutenants Jack Hawkins and Michael Dobervich; and two Army sergeants, R. B. Spielman and Paul Marshall. When Corregidor finally fell at 12 Noon on May 6, 1942, the formal surrender came as a surprise to almost none of the seven thousand Americans and five thousand Filipinos on The Rock, particularly those of us who had served as staff officers. The surrender was a logical climax to a series of disasters which had been highlighted by the evacuation of Manila and the Cavite Naval Base on Christmas Eve, the heavy aerial bombing of Corregidor on December 29, 1941, the departure of high United States and Philippine officials in February, and the withdrawal to Australia of General MacArthur and members of his staff in March. Then on May 9, 1942, came the surrender of Bataan. There were approximately four times as many men on Bataan, only four miles away, as we had on Corregidor. We knew that The Rock was next. The Japs were hitting us with everything they had. It was only a matter of time. As the time for the surrender drew near, one of us (McCoy) was in the tunnel occupied by the Navy and the other (Mellnik) was stationed in the Headquarters Tunnel occupied by the Army. We were not quartered together in the same prison until some weeks after our capture. Thus, each of us saw different phases of the same event; and in telling the story of what happened while we were official military prisoners of the Japanese in the Philippines, each has elected to tell the part with which he is most familiar. Commander McCoy: Even in the depths of the solid rock tunnels of Corregidor we could feel the vibrations of the almost constant Japanese barrage. One night toward the end of April the barrage lifted for a short time. Hundreds of people went out into the open for a breath of air and a smoke. It was pitch dark. The only light came from the few stars, and the occasional faint glow of a carefully shielded cigarette. Suddenly the group of people around the tunnel entrance seemed to be struck by lightning. There was an awful glare and a mighty crash. A salvo of Japanese 240mm shells had landed in the midst of this group. Just that one salvo -- no more. Fortunately it was dark and the survivors did not have to look on the scene around them. But it was four hours later before the hospital staff completed their amputations, transfusions, brain operations and other work. About midnight that night I went off duty in the radio shack in the Navy Tunnel, and I went out to the tunnel entrance where the tragedy occurred. There I found one of the nurses who had helped the doctors during the evening. She was crying her heart out on a sandbagged machine gun. I did not know whether she had suffered a personal loss, or whether our situation in general had become too much for her. She obviously had come out into the darkness to hide her emotions from the wounded, so I tiptoed away and did not disturb her. Lieutenant Colonel Mellnik: About the last week in April it became evident from the volume and distribution of enemy fire that a landing would be attempted on Corregidor. Our heavy artillery was being knocked out more rapidly than we could repair it. The headquarters of General Wainwright and General Moore were in Malinta Tunnel. In this tunnel were the hospital, machine shops, food and ammunition reserves, radio station, and administration units. I was directed to form and take charge of the Malinta Tunnel guard. The purpose of this guard was to prevent a Jap raiding unit from getting in and capturing the headquarters units, thus bringing about the surrender of Corregidor. The tunnel runs east and west, with additional hospital tunnels running north and south. The guard was composed of administrative personnel. On the night of May 5, about 8:00 P.M., the guard was alerted -- an enemy landing appeared very likely. Enemy 240mm shells were falling all over the place. The tunnel system literally rocked from the impact of 240mm salvos -- salvos exploding so fast they sounded like a giant machine gun. Hospital beds jumped all around, medicine cases had to be lashed down. In the previous week we had opened up six additional laterals in the tunnel to take care of the wounded. The tunnel system was now mostly hospital. As fast as we used up supplies of food or ammunition, this storage space was turned into a hospital area. Even so, we had to build triple-decker beds to accommodate all the wounded. The nurses behaved like champions. The wounded realized fully the hopelessness of the situation and made little complaint. About 4:00 A.M. on May 6th I made a routine visit to the hospital tunnel. Everything was normal. Breakfast was being served. One blonde nurse winked at me and sang out, "If you fellows can't chase those Nips away, we nurses will have to get out there and do it." I stopped at the desk of another nurse. She was recording the amount of morphine used up in the past 24 hours. "I know this recording is silly," she said. "It won't matter in a few days whether the records are here or not. But I've got to believe that it does matter -- I've got to." The entrances to the tunnel were lit up by the glow of motor vehicles which had been hit by shells and were burning. I checked on a machine gun position outside the tunnel. There I found Sergeants Spielman and Marshall (who knew as little as I of the experiences we were to go through in the months to come). Their machine gun pit had been blasted out several times during the night. They were digging themselves out of a pile of rubble which had covered their gun in the explosion of a heavy salvo. Sergeant Spielman grinned ruefully and said, "Nothing like this ever happened to me in Crezo Springs, Texas. If Crezo Springs turns out many like Spielman, Crezo Springs is all right. About dawn of the morning of May 6th, we received a report of three Jap tanks having landed in the fighting area. Our anti-tank guns were of World War I vintage. The road leading through the headquarters tunnel had anti-tank barricades at various intervals. These consisted of concrete pillars to which were attached iron railroad rails. During the night these rails had been removed to permit an ammunition carrier to get through, and at one place the barricade was exposed to enemy fire. When I called for volunteers to replace the tank barrier, Sergeant Scott O'Neils stepped forward with a detail of ten men. They replaced the rails without a casualty. Sergeant O'Neil was awarded the Silver Star. No enemy tank got near the headquarters tunnel until after the surrender. By 9:00 A.M., on the day of the surrender, Jap snipers had infiltrated our beach defense lines in some force. Machine gun bullets whizzed around the tunnel entrances, adding a new note to the scream of falling shells and the blast of exploding bombs. I had often wondered what the reactions of men would be under these conditions. I had expected fear, anxiety, emotionalism in all its forms. I found nothing but matter-of-fact business. An enemy machine gunner was discovered on a ridge, and a squad of men calmly discussed the manner of his liquidation. A puff of dust in front of the machine gun would result in that rifleman being joshed for the poor use of his rifle. When the machine gun was finally knocked out the riflemen paused for a cigarette. After the scream of bombs and shells, ordinary bullets flying around them caused little comment. As one rifleman put it, "All them Japs wear glasses -- they can't see well enough to hit us." At 10:00 A.M., orders were sent to all artillery units to destroy their guns and installations by 12 Noon. There were few guns left to destroy. Most of the guns had been destroyed by the enemy. However, stocks of ammunition, power plants, and other installations and supplies had to be made useless to the enemy. At Noon on May 6, 1942, a gloomy pall fell over The Rock. Then the months of constant strain began to do their work. Some men cried quietly, others became hysterical. Exactly on the stroke of twelve a hospital corpsman came into General Moore's office, General Wainwright having left the tunnel to arrange the ~ surrender. The corpsman was sobbing, tears were streaming down his face. He sat down and sobbed out what we all knew: "There's a white flag waving at the hospital tunnel entrance". To most, the surrender came as a relief. But the silence following the surrender was worse than the shelling. It was uncanny, awful. The sudden opening of a door, a falling chair, would make us jump and flinch. In the moment of surrender none of us thought of tomorrow, for there was no tomorrow. For us, the end had come. Commander McCoy: At 11:55 on the morning of May 6, 1B42, I wrote out the Navy's last message from The Rock and handed it to a radioman 1/c at the sending apparatus. "Beam it for Radio Honolulu," I said. "Don't bother with code." Then the message began to go out. "GOING OFF AIR NOW. GOOD BYE AND GOOD LUCK. CALLAHAN AND MCCOY." It was three hours before the Japanese marines finally swarmed into the Navy tunnel on Corregidor. During that wait, I had time to think of the two chances I had had to escape from Corregidor during the siege, both of which I had turned down. The first of these escape opportunities came on the day after Christmas, 1941. Outside the Bay was the sailing ship "Lanakai", a two-master which had once been used by Hollywood and Miss Dorothy Lamour in the motion picture, "Typhoon". There was a place for me aboard, and I could have received permission to go; but I was radio materiel officer for the Navy in that area, and I knew that my services would be needed in our communications with the outer world. I outfitted the "Lanakai" with certain equipment and provided enlisted personnel to operate it. The "Lanakai" got through. Another escape opportunity presented itself in the month before Corregidor fell. A small group of us came into possession of the sloop, "Southern Seas” completely outfitted with charts, food, fuel for the auxiliary engine, and new sails and rigging. The "Southern Seas" was anchored off The Rock, and a few of us intended to board her and make for the open sea at the last moment before capture. In the last days before surrender, however, all of us were too busy to think of escape. The Japs began to hit The Rock with a minimum of 5,000 shells a day, mostly of about 150 millimeter, along with some 240's and 105's. On one day they blasted us with 16,000 shells, mostly fired from gun replacements on Bataan. Much of this fire could not be returned. The Japs massed much of their artillery in the No. 2 hospital area on Bataan, an area which we knew to contain at least 6,000 American and Filipino wounded. The Japs literally used our wounded to make ramparts around their gun. And when I got ready to use the "Southern Seas" it was too late. Two days before the surrender the sloop was stolen from her moorings by some of our own people on The Rock. Whoever took her obviously did not know our recognition signals. As she passed one of our outer bastions she did not answer a challenge. She was riddled with gunfire and sunk. Presumably all aboard were killed. There were approximately a hundred and twenty-five Naval officers and men in the Navy Tunnel when the first Japs came in, some three hours after the surrender. The Japs were ready with bayonets and grenades. (They entered the Army Tunnel with tanks and flame-throwers.) When they saw no sign of opposition they lowered their rifles and became almost jovial as they got down to the pleasant business of looting. This practice is officially forbidden, so Japanese officers made a point of not entering the tunnel for almost two hours after the enlisted men first appeared. By that time everything of value had been taken. The Japs seemed to prize above all else our wristwatches. I saw one burly Jap marine with watches all the way up to one elbow, half-way up to the other, and with a bayonet aimed at the stomach of another Jap who was trying to beat him to an additional prize. Besides watches, fountain pens also were highly prized by our captors. There were numerous scuffles between the Japs over possession of these articles. Some of the Japs in the Navy Tunnel could speak a little English. They told us they had been used as assault troops at Hong Kong and Singapore. We were only slightly comforted at being told that we had put up the stiffest resistance they had met. The first officers to enter the tunnel were non-coms, sergeants. As the first one entered, a Jap soldier was hopefully searching me -- everything of value in my possession had long since been taken away from me. The Japanese sergeant slapped and cuffed this soldier brutally, the soldier standing rigidly at attention, and the sergeant blandly ignoring the evidence of previous looting that was in plain view. But Japanese battle action did not end with our surrender. On the second day after our capitulation, Japanese planes flew at minimum level over The Rock and dropped bombs, first making sure that their own men were out of the way. Casualties on our side were alight, and the Japs evidently were only bolstering a threat made to General Wainwright that, unless all the forces in the Visayan Islands surrendered, all on Corregidor would be massacred. And it did not take us long to learn the temper of our captors. A gun crew on nearby Fort Drum, called "the concrete battleship", had fired into a Japanese assault party a few days before Corregidor fell. A high-ranking Japanese officer was killed. This officer's brother, on the Jap headquarters staff back in Manila, ordered that the men on Drum be given special attention. They were beaten and hazed unmercifully for forty-eight hours. Another incident occurred when a Japanese sentry began to beat an Army enlisted man without provocation -- we did not know at the time that such actions were commonplace. The soldier made as if to hit the sentry with his fists. He was shot dead by another sentry before he could complete the motion. Lieutenant Colonel Mellnik: Two days after the surrender the 7,000 Americans and 5,000 Filipinos were awakened at night and ordered out of the tunnels on The Rock. We did not know where we were going, but were prodded along in the darkness at the point of Jap bayonets. We soon saw that we were being concentrated in the Kindley Field Garage area. This had formerly been a balloon station, but the roof had been torn off by Jap shells, and the walls knocked down. It was now only a square of concrete, about 100 yards to the side, and with one side extending into the water of the Bay. The twelve thousand of us were crowded into this area. All the wounded who could walk also were ordered to join us, many with broken bones or serious injuries. For seven days we were kept on this concrete square without food, except for that which could be scavenged by the few of us who were formed into work parties, to clear away the dead and to remove the rubble caused by Jap artillery. Most of the prisoners got nothing to eat during those seven days. There was only one water spigot for the twelve thousand. A twelve-hour wait to fill one canteen was the usual rule. There were no latrines in the area, except some shallow holes which the Japs allowed us to dig on the outskirts of the concrete, The heat was at its worst. Men fainted by the score, and were passed from hand to hand down to the waters of the Bay. Each morning a hundred or more unconscious were taken out of the area back into the tunnel. I do not know what happened to them. We were covered by clouds of black flies, and dysentery had already begun to spread among us. Our dead, their bodies bloating, lay on The Rock for several days. The Japs doused their own dead with oil and burned them in huge pyres, mostly on Bataan. (Before a Japanese was burned, a hand or arm was cut off and burned separately, and these ashes were returned to Japan.) After seven days we were given our first food -- one mess kit of rice and a tin of sardines. On the afternoon of May 22nd the Japs loaded us onto three merchant ships of about 7,000 tons each. There were approximately four thousands of us on each ship, designed to accommodate 12 passengers. We remained aboard all night, in the most suffocating condition imaginable. We got under way the next morning and we were surprised to observe that we were not being taken directly to Manila, as was the case with the one ship loaded only with captive Filipinos. We were to learn later that there was a reason for this. Instead, our ship dropped anchor off Paranaque, a suburb south of Manila. Here we waited until the heat of the day had almost reached its peak. Then we were jammed into barges. After an hour in the sun we were taken to within a hundred yards of the beach. This was surprising to us, for the barges could easily have run right up to the beach. We were ordered to jump overboard in water up to our armpits and march to the beach, where we formed four abreast. Then we knew we were to be marched through Manila presenting the worst appearance possible -- wet, bedraggled, hungry, thirsty, and many so weak from illness they could hardly stand. This was our captors' subtle method of convincing the subject peoples of the Philippines that only the Japanese were members of the Master Race. Commander McCoy: I had fared better than most of the prisoners, for I had been kept in Malinta Tunnel with Generals Moore and Drake and with the senior Naval officer, Captain K. M. Hoeffel, USN. Thus I was able to offer furtive help to some of the marchers in the line of prisoners. The Japanese had intended this to be a triumphal victory parade, but there were few signs of happiness on the faces of the Filipinos who lined our route. Instead, there were many tears and many carefully-shielded signs of encouragement. Armed Japanese guards marched at our side at intervals, and the route for its entire five miles was patrolled by Japanese cavalry. As we marched down Dewey Boulevard there were many landmarks that had become familiar to me in my two-year tour of Navy duty in Manila. As we passed the High Commissioner's residence we noted Japanese flags flying -- this was now the headquarters of General Homma. We passed the Elks Club, with the Army-Navy Club visible at a distance. At the Legislative Building we turned right, passed over Quezon Bridge and onto Ascarraga Street. All during the march the heat was terrific -- it has been my observation that the Japanese deliberately wait for the hottest part of the day before moving American prisoners. The weaker ones in our ranks began to stumble during the first mile. No doubt they had been weakened further by the cramped night on the ships, and the lack of food. These were cuffed back into the line and made to march until they dropped. If no guards were in the immediate vicinity, the Filipinos along the route tried to revive the prisoners with ices, water and fruit. These Filipinos were severely beaten if caught by the guards. As prisoners fainted, they were picked up by trucks which were following the march for that purpose. When we were within two blocks of our destination, Old Bilibid Prison, I noticed that Lt. Col. Will B. Short, USA, was walking in an unusual, stumbling manner. I was not near enough to help him. Suddenly he fell forward, disrupting the line of march. Japanese guards happened to be nearby. They ordered two Army enlisted men to pick up Col. Short, holding him under each armpit. The march was ordered to resume, and the unconscious man was dragged in this manner the remaining two blocks to Old Bilibid, where the Army enlisted men were ordered to throw him on the prison floor. I started to kneel down at his side but a Japanese bayonet was shoved at my chest in a very business-like manner. Short had not moved, and had been given no medical attention when, two hours later, I was ordered with Captain Hoeffel and several Army staff officers to the elementary school at Pasay. In this school was the Navy Hospital Unit from Canacao, Carire. The Unit's medicines had been confiscated, except for that which a few doctors had managed to hide among their personal effects. An hour after we reached Pasay, Lt. Col. Short was brought in and placed on a mattress on the floor. Naval doctors worked on him for nearly an hour, while the rest of us stood about and wondered what was to happen to us next, and what was to be our fate. In all the entire group, only Lt. Col. Will B. Short had no worries for the future. Lt. Col. Will B. Short, United States Army, was dead. Death was no stranger to any of us who had gone through the Battle of the Philippines, but we were to learn about a new kind of death. For instance, while I was at Pasay a group of 300 American prisoners who had been captured on Bataan and had been at Camp O'Donnell passed through on their way to a work detail in Batangas. All were in a deplorable condition -- the story of the "death march" to O'Donnell, after the surrender of Bataan, probably will come to rank with the worst chapters in the story of human cruelty. And the next morning after their arrival, 18 of these men were unable to walk, and they were replaced by eighteen healthier prisoners already at Pasay. Later on, we were to meet up with this party again -- at least, out of the original party of 300, we were to meet up with the thirty-odd who had not died from hunger, cruelty or disease. Later on, although we did not know it at the time, we were to be transferred to the prison camp at Cabanatuan, where death was a part of our way of life. CHAPTER TWO

"The Death March From Bataan" It did not take us-long to learn that the hardships we had faced in battle were, if anything, much less severe than those awaiting us as military prisoners of the conquering Nipponese. With the surrender of Corregidor on May 6, 1942, one month after the fall of our larger force on Bataan, organized American resistance to the Japanese in the Philippines had come to an end. At first, hope ran high among the thousands of American and Filipino fighting men who had been forced to lay down their arms in defeat. There was a feeling, particularly among the enlisted men, that Uncle Sam had merely been caught off balance by a puny but cunning foe in the first round, and that the knockout punch even now was on the way. In Old Bilibid Prison, in Manila, this feeling was expressed in such statements as, "We won't be here long -- a couple of weeks, maybe, or a month". But those of us who had served as staff officers, and who knew something of the problems involved, were not so optimistic. We all wanted to believe the best, but we knew that the United States had suffered her worst defeat in history, and we knew that the job ahead would be long and hard. And from our few furtive contacts with civilian Filipinos outside our prison walls, we learned that the Japs were losing no time in bringing the New Order in East Asia to the Philippines. It is surprising how much news does seep into a prison, no matter how heavily guarded. We had the additional advantage of two listening points, one of us (McCoy) being in prison with the Army and Navy staff officers at Pasay, and the other (Mellnik) in Old Bilibid. All Filipinos, we learned, were now forced to bow to the Japanese invaders on the streets of Manila. All streets with American names, incidentally, were being given Japanese names. All commercial enterprises were being given Japanese direction, and cultured Filipinos were being subtly told that their place in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere was in the rice paddies and abaca fields. Education was being suspended, and the Japanese were announcing in forcible terms that they were benevolently decreeing a return to the original Filipino "culture". This meant that, for Filipinos, there was to be no more such "foreign. corruptions" as modern plumbing, cooking on electric stoves, going to movies, riding in automobiles, wearing silk stockings or using cosmetics. In addition, the English language (spoken by almost every Filipino over 35) was to be forbidden, and was to be replaced by Nippon-Go, a sort of simplified "basic Japanese". And the Japanese conquerors had already begun a systematic looting of the Philippine Commonwealth. Cities were being stripped of all articles needed by Japan. Electric fans, refrigerators, machinery, household appliances, automobiles, scrap iron -- all were being taken to Japan. Even rice, never too plentiful in the Philippines, was being sent to Japan. Of course the Japs were paying for these things, or some of them, and paying high prices, too -- the printing presses were turning out worthless Japanese Occupation Currency at top speed. But few of the prisoners captured on Corregidor were to remain long in Manila. We were shortly to learn that, although many civilian internees were to be quartered in the Manila area, the Jape had other plans for those of us who were American prisoners of war. Lieutenant Colonel Mellnik: McCoy was still at Pasay when I learned, on May 27, 1942, that I was to be transferred to the prisoner-of-war camp at Cabanatuan, about seventy-five miles north of Manila in the Province of Luzon. It was their custom when American prisoners were to be moved, the Japanese waited until the heat had reached its peak before loading some fifteen hundred of us into iron boxcars. There were a hundred men to each car, with no room to sit or lie down. The cars were tightly closed so that there was no ventilation. With the sun beating down on the metal roof, the inside of the car was like an oven, with no water or sanitary facilities available. Although several men fainted, there were no deaths on the trip. When we got off the train at Cabanatuan we were put into an open field surrounded by barbed wire and patrolled by sentries. We were told that we would remain overnight. Curious and sympathetic Filipino civilians watched us from a respectful distance, some of them bearing bananas, papayas and mangoes, but the Jap sentries kept them warned back with their bayonets. Lt. Col. Carl Englehart and I were trying to keep cool under a pup tent which we had put up. The sight of the fruit was tantalizing beyond description. Carl had served as a language student in Japan and, finding a few pesos between us, he spoke in Japanese to a nearby guard, asking him to buy us some fruit. The Jap seemed delighted at hearing an American speak his language. Much to our surprise he got us the fruit, and then hastened away. We had been on a steady diet of boiled rice and watery soup since our capture (when we got anything to eat at all) and we were wolfing down the fruit when the Jap guard returned, smiling and bowing. He spoke to Carl in Japanese. "Something's up," Carl said to me. "The Jap C.O. wants to see us." The Jap guard escorted us to the nearby house of the Japanese commanding officer at Cabanatuan. This personage greeted us in perfect English, but we could see that he was in a murderous mood. After the greeting, the Jap commander fixed us with what seemed an interminable scowl. Then he spat at us suddenly: "What do you Americans mean by bombing and machine gunning Japanese cities?" I am sure that Carl was as dumbfounded am I. But I also felt a wild hope that the American invasion of Japan was under way. We hastily assured the Japanese commander that we knew nothing about any attack on Japan. He launched into a long tirade against the United States and particularly against President Roosevelt, during which we learned that he was referring to the American air raid on Japanese cities (later we learned that this was the Doolittle raid, with planes which took off from a carrier in the Pacific). At every pause in his tirade, we would get in a few words protesting our innocence. The Japanese officer finally indicated that he had finished his tongue-lashing. As we turned to go he said, "There are fifteen hundred of you out in that stockade. If I thought a one of you sympathized with the bombing of Japanese cities, I would turn machine guns loose on you". There was not the slightest doubt in our minds of his sincerity. The next day, when the sun had reached its zenith, we began our march of twelve miles to our prison camp. Not one of us was fit for marching. For five months we had been under siege on Corregidor, under constant strain. During more than three weeks of captivity the Japanese had not provided us with a single decent meal. Many of us were ill. As we passed small Philippine barrios, or villages, on the march, the inhabitants seemed anxious to help us. Small children darted to our side and gave us balls of boiled rice. Those that were caught by the guards, however, were cuffed unmercifully. After we had gone about eight miles, I began to suffer intolerably. The heat was unbearable. My heart was pounding and my pack grew heavier by the minute. I began to count the steps, and long for the sight of a new kilometer post beside the road. Occasionally I would pass a man who had fallen out, gasping for air, or white and still in unconsciousness. As the Jap guards came along they would encourage these men to keep moving, using the point of their bayonets. Some men managed to get up and stagger further. Others had reached the point when an inch of bayonet point brought no response. These men were later picked up by trucks -- those who were still alive. After a brief stay at a temporary camp, we reached the Cabanatuan Prison on May 29, 1942. This camp had been built originally as training quarters for Filipino detachments of the United States Forces Far East, and no preparation had been made for our coming. But the lack of food did not bother most of us. We were glad to drag our weary bodies into the barracks and throw ourselves down on the bare floors. The next morning the camp was electrified by a report which quickly swept through our ranks. During the night three young Naval Reserve ensigns had simply walked off into the darkness of the jungle and had successfully escaped. We were to hear more from these men later; and the Japanese lost no time in discovering which of the three prisoners were missing. Barbed wire was hastily thrown about the camp, and sentry towers were built at short intervals. Then the grim Japs went through the camp and formed us off into groups of ten. If any one member of any group escaped, we were told, the other nine would be shot. These squads quickly became known among ourselves as "shooting squads, and each prisoner counted himself a member of his own "shooting squad". We had barely settled into the prison at Cabanatuan when, on June 2nd, the first detachments of prisoners from Bataan began to arrive at our camp. We were appalled at their condition, and even more appalled when we learned what had happened to them on what they all called "the death march from Bataan". These prisoners arrived at Cabanatuan in trucks for the simple reason that only a very few among them were physically able to stand up and walk a hundred yards. In the first truck to arrive was a young enlisted man who at one time had served as my orderly. He staggered to my side and, holding himself up by feebly grasping at my shoulders, he sobbed out, "Sir, is it different here -- will they treat us like humans?" I tried to comfort the boy by telling him that everything would be all right, and he staggered away, still sobbing. The Bataan prisoners who were joining us now, and who had been prisoners a month longer than we had, were the most woe-begone objects I have ever seen. They were wild-eyed, gaunt, their clothes in tatters. Many had no equipment of any kind, and some clutched at rusty tin cans which they used as mess kits. These men had their own doctors with them -- the medical detachments from Bataan -- but the doctors had no medicines, and they were as sick as the men. One of these prisoners was a quartermaster lieutenant who was in the last stages of what was called "wet beri beri". He was horribly swollen from his hips down, was in frightful pain, and constantly expressed the fear that if the swelling rose above his hips to his heart he would die. We finally got a Japanese doctor to examine him. The doctor said that if the lieutenant's condition had not improved "in a day or two" he would return with some medicine. The next day, however, the man was dead. In death he was not alone, for soon the first chore of our day was the removal from our barracks of the bodies of men who had died during the night. Commander McCoy: Mellnik had been at Cabanatuan about five weeks when I learned that I also was to be transferred there. After being captured on Corregidor, I had spent my first few days at Pasay, where the Japs had turned an elementary school into a prison for the senior Army and Navy staff officers. When these officers were removed from Pasay -- presumably to be taken to prisons in Japan or Formosa -- I was transferred to Old Bilibid in Manila. At Old Bilibid I was assigned to such jobs as cleaning out Japanese latrines and sewage systems. On another occasion I took a detail of enlisted men, under heavy guard, to Rizal Stadium, where the Japs had concentrated mountains of captured American quartermaster supplies. Much of these supplies consisted of food, and the Japs told us as we loaded it on trucks that it was to be sent to the American prisoners of war. During my eleven months of captivity I was never to see any of this food. In fact, and except for boiled rice, I was never to see much food of any kind. After a tortuous trip from Manila, I arrived at the prison camp at Cabanatuan on July 7th, less than two months after the camp was formed. My first impression of Cabanatuan was one of utter desolation and hopelessness. As I was mustered into the camp I was first searched by Japanese guards. The only things of value they found on me were two small bottles containing quinine and sulfa drugs, which had been given me by a doctor friend at Old Bilibid. The Japs confiscated this medicine. One of the first persons I saw was an Army major whom I had met at Amy-Navy parties in Manila, and whom I had talked to on several pleasant pro-Pearl Harbor occasions in the Transportation Club in the Marsman Building. "You look awful, "I said to him, staring at his gaunt, stricken appearance. "I was on Bataan, "he said. "I made the death march" I had already become aware of an awful stench about the camp, but for the first time I noticed that, outside of each barracks, there was a neat row of bodies. Somehow I knew that the bodies had been there for some time -- clouds of flies arose from them when groups of prisoners walked nearby. "Good God!" I was pointing. The Army major looked casually at the row of bodies and said, "You'll get used to that." He was about to say more when he suddenly clutched at his stomach with both hands and began to run in a broken gait, managing to fling over his shoulder a muffled "See you later". I soon learned that this hurried "see you later" was a common parting salute at Cabanatuan, as prisoners suffering from dysentery and other disorders struck out in the direction of the latrines. The worst sufferers were the prisoners from Bataan. I heard the story of the death march from Bataan to Camp O’Donnell from many responsible officers at Cabanatuan, but I heard it most often from the major I had recognized on my arrival at the camp. This officer is a graduate of West Point, and although his name has been supplied to military authorities it will not be used here for reasons which will become obvious. After the fall of Bataan on April 8, 1942, approximately 10,000 American and 45,000 Filipino prisoners were marched to San Fernando, Pampanga, a distance of about 120 miles. These prisoners were marched in different groups, and some were treated worse than others. In most cases they went for days without water -- one officer told me that he went so long without water that, presumably due to dehydration, he observed crystals in his urine. My friend the Army major -- I shall call him Major Gunn -- said he went for many days without food; he did not remember the exact number, as he had lost count, but it was "more than a week". Then he was allowed one mess kit of rice. "We often passed running streams," said Major Gunn, "but the Japs seldom allowed us to drink. A few prisoners tried it, mostly Filipinos. They were shot down and left dying where they fell. If we drank from muddy carabao wallows, though, the Japs didn't seem to mind. That's where so many hundreds of us got dysentery, I suppose." During the long march these groups of Bataan prisoners passed through the village of Lubao, and were kept there overnight. They were quartered in a warehouse of galvanized tin, with no windows but with a few small grid openings near the floor. First the Japanese would herd as many prisoners into the building as seemed possible, requiring them all to stand. Then, when the building was completely full, more prisoners were placed just outside the door and a steel cable was attached to one corner of the building. Several guards then took the other end of this cable and by pulling it taut, they squeezed all those outside into the building. The sliding door was then closed and secured for the night. During the night no prisoner was allowed outside this building for any reason whatsoever. Many of the prisoners were ill, or were walking wounded. Since there were no sanitation facilities inside, and since several persons died each night, it is easy to understand why those who made the death march always shuddered when they described their overnight stop in the village of Lubao. While on the march, regular clean-up squads of Japanese followed at the rear to dispose of the prisoners who fell out, both Filipinos and Americans. Filipinos were bayoneted or shot, and left where they fell, but Americans were usually taken some distance from the road. At the end of the day the Japanese usually dispatched those prisoners who seemed so weakened that they would not be able to make the march on the following day. Different methods were used to dispose of these weakened prisoners. There were many cases of burial alive, often with the forced assistance of American officers. Some of the prisoners were forced to dig their own graves. The victims of this treatment were most often Filipinos, but there were some cases of Americans being buried alive. "On the march," Major Gunn said, "the Japs treated the Filipinos even worse than they did us. The Japs claimed that in aiding the Americans the Filipinos had turned against their own blood, that the Filipinos were Orientals who had betrayed the Orient. When a Filipino fell out on the march he was shot or bayoneted where he lay. Then he was dragged to the side of the road and left. In the case of an American, the Japs at least took him out of sight of the other prisoners before they put him out of the way." Major Gunn's worst memories were intensely personal. They centered things which he, an American officer, had been forced to do on threat of death; and, for this reason, his real name is not being used. "The first time it happened, said Major Gunn, "I didn't know what was up. A Filipino had keeled over -- he had been stumbling for hours -- and the Japs dragged him to a ditch about a hundred yards from the road. I was taken out of the line and escorted to where the Japs had placed this unconscious Filipino in the ditch. One of the Japs handed me a shovel. Another jabbed a bayonet into my side and gave an order in Japanese. I did not understand. A Jap grabbed the shovel out of my hands and demonstrated by throwing a few shovelsful of earth on the Filipino. Then he handed me the shovel. God!...It doesn't help to tell myself that the Filipino, and others later, were already more dead than alive....The worst time was once when a Filipino with about six inches of earth over him suddenly regained consciousness and clawed his way out until he was almost sitting upright. Then I learned to what lengths a man will go, McCoy, to hang onto his own life. The bayonets began to prod me in the side, and I was forced to bash the Filipino over the head with the shovel and then finish burying him." Major Gunn told this story to me several times, and he never told it with an excuse for his own conduct. It was unspoken between us that a man already crazed by thirst and hunger, and already at the point of exhaustion, is not a rational being; automatic reflexes alone will cause him to hang onto his existence with all the remaining life that is in him. Often, after talking about the death march from Bataan to O'Donnell, Gunn would pause for a while and then say, "Those things don't happen to Americans, McCoy. I know we've heard of Hitler starving and killing people by the thousands; and we've heard of the Japs using living Chinese for bayonet practice. But we're Americans, McCoy. Nobody ever taught us about things like that." When the Bataan prisoners finally reached San Fernando, on the way to O'Donnell, they were jammed one hundred into a boxcar and, always in the heat of the day, given a two-hour ride to Capiz, Luzon. Then they marched the remainder of the way. Conditions at Camp O'Donnell were, if possible, as bad as those along the route of march. The camp commander announced that he had not been notified that such a large number of prisoners was being sent. He had no facilities for them. This the prisoners soon saw, for there was only one water spigot for the many thousands, and all the running water in the vicinity rapidly became polluted by the sick and the dead. And, in a regular public speech to the assembled prisoners, the Japanese camp commander stated that he did not like Americans, and that he did not care how many died. Lieutenant Colonel Mellnik: When the O'Donnell prisoners arrived at Cabanatuan, or what was left of them, the American leaders in our group did their best to compile a list of those who had died previously. This list was kept up to date as others died at Cabanatuan. As far as I know, the list is still at Cabanatuan, and it contains many hundreds of names which have not yet been announced by the Japanese. The death rate at O'Donnell, we learned, had been frightful. Many of the prisoners had fought on to the end at Bataan although wounded or ill. After the death march there was hardly a man who was not clearly a hospital case by the time he reached O’Donnell. Careful estimates from many of the officers who survived place the number of Americans who died there in April and May at twenty-two hundred. I have been assured that this number is conservative, despite the confusion which necessarily existed in the midst of such wholesale sickness and death. This confusion was heightened by the fact that Filipinos were dying at the rate of five hundred a day, with Americans dying at the rate of fifty a day. The problem of burial of these bodies became extremely acute (just as it also became at Cabanatuan). The Japs would not help with this work. The Filipinos and Americans were so weak that there were not enough healthy men to dig the graves. As a result, the camp became so littered with bodies that it was sometimes hard to tell the living from the dead. This death rate at O'Donnell finally became so alarming that the Japanese began to discharge the Filipinos as soon as they became ill, hoping that they would die in the bosom of their families and thus free the Japs of responsibility. American officers say that, of the 45,000 Filipinos who started out from Bataan on April 9, 1942, fully 27,000 had died by the end of May, when the surviving Americans were transferred to Cabanatuan. Commander McCoy: "You won't like it here," Major Gunn said to me, shortly after I arrived at Cabanatuan. "Had dysentery yet?" "No" "Malaria?" "No. I thought I had a chill last night. Maybe it was the food." "What food?" said Major Gunn sourly. More will be told about the food at Cabanatuan later. But at this time there were already many cases of vitamin deficiency. Our doctors had no medicines to speak of, so they advised us to crush charcoal and mix it with our rice as a slight medicinal aid. "I suppose the charcoal pudding didn't agree with me," I said. "A chill, eh?" said Major Gunn. He shook his head. "You're being initiated into the brotherhood, all right." When ten of us escaped in April of 1945, reaching the United States separately some months later, Gunn and many others were on the definite downgrade in health -- those who were still alive. I doubt very much if Gunn is still among the living. But I know that if he is dead -- he and many others like him -- he died without cracking up, and while still fighting to stay alive. A few of the prisoners may not have been entirely sane when last we saw them, but there had not been one case of outright mental crack-up. I still don't know why a lot of us didn't become raving mad. "You won't like it here," said Major Gunn. I followed his eyes. A platoon of Japanese troops and an officer were swinging down the road toward the camp, singing a marching song. Rumor in the camp had it that this group had guerillas. We soon saw that the rumor was correct. The platoon marched in military order up to our stockade and halted on an order from the officer. Then they impaled a gory Filipino head on a tall fence post near our gate. This obviously was a subtle warning against any infraction of our prison rules. We were soon to learn that it was not an empty threat. CHAPTER THREE