|

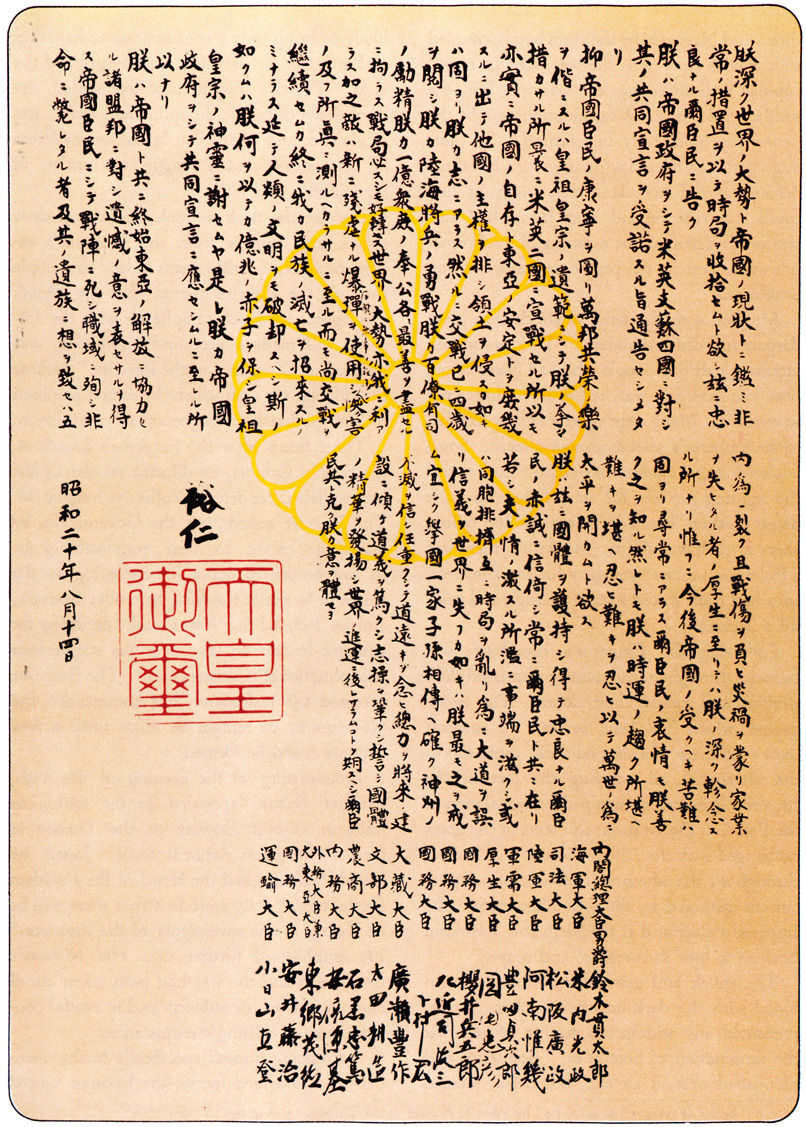

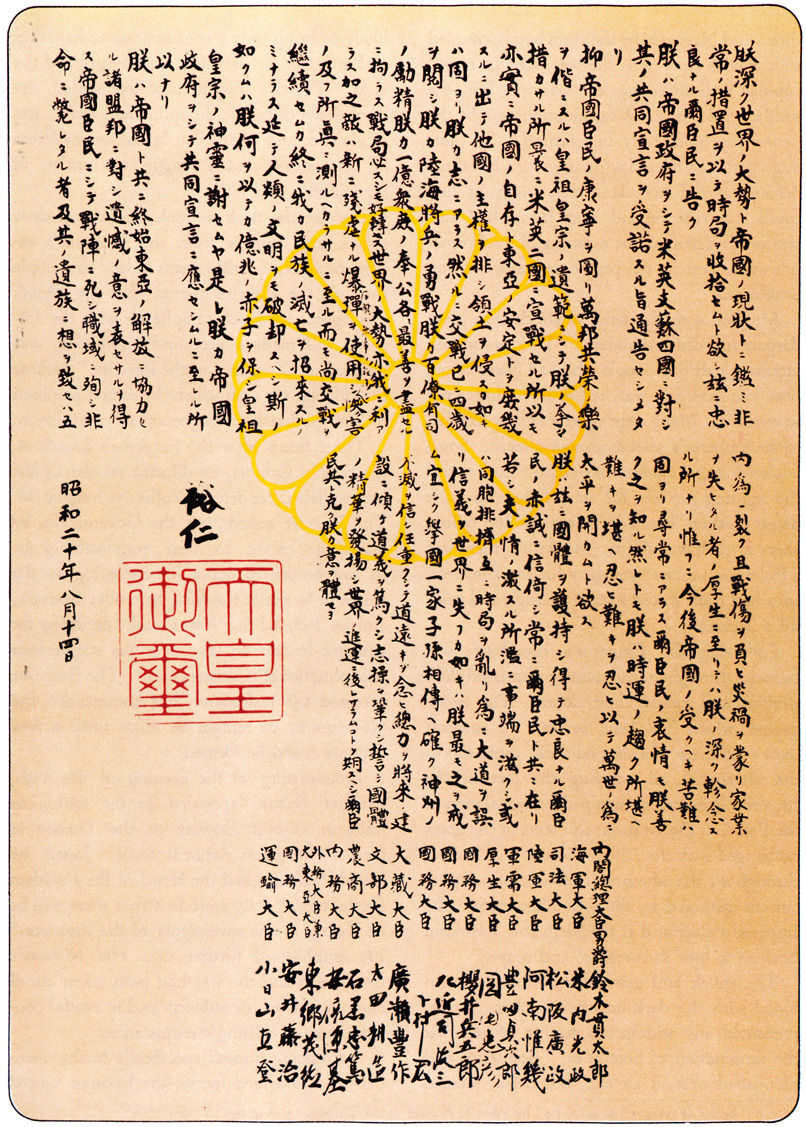

"I have noted in red

the subtle dissembling of Hirohito." -- Roger Mansell

August

14, 1945, New York Times

TO OUR GOOD AND LOYAL SUBJECTS:

After pondering deeply the general trends of the world

and the actual conditions obtaining in our empire today,

we have decided to effect a settlement of the present

situation by resorting to an extraordinary measure.

We have ordered our Government to communicate to the

Governments of the United States, Great Britain, China

and the Soviet Union that our empire accepts

the provisions of their joint declaration.

To strive for the common prosperity and happiness of

all nations as well as the security and well-being of

our subjects is the solemn obligation which has been

handed down by our imperial ancestors and which we lay

close to the heart.

Indeed, we declared war on

America and Britain out of our sincere desire to

insure Japan's self-preservation and the

stabilization of East Asia, it being far from our

thought either to infringe upon the sovereignty of

other nations or to embark upon territorial

aggrandizement.

But now the war has lasted for nearly four years.

Despite the best that has been done by everyone-the

gallant fighting of the military and naval forces, the

diligence and assiduity of our servants of the State and

the devoted service of our 100,000,000 people-the

war situation has developed not necessarily to

Japan's advantage, while the general

trends of the world have all turned against her

interest.

Moreover, the enemy has begun

to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the

power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable,

taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we

continue to fight, it would not only result in an

ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese

nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction

of human civilization.

Such being the case, how are we to save the millions of

our subjects, or to atone ourselves before the hallowed

spirits of our imperial ancestors? This is the reason

why we have ordered the acceptance of the provisions of

the joint declaration of the powers.

We cannot but express the deepest sense of regret to

our allied nations of East Asia, who have consistently

cooperated with the Empire toward the emancipation of East Asia.

The thought of those officers and men as well as others

who have fallen in the fields of battle, those who died

at their posts of duty, or those who met with death

[otherwise] and all their bereaved families, pains our

heart night and day.

The welfare of the wounded and the war sufferers and of

those who have lost their home and livelihood is the

object of our profound solicitude. The hardships and

sufferings to which our nation is to be subjected

hereafter will be certainly great.

We are keenly aware of the inmost feelings of all of

you, our subjects. However, it is according to the

dictates of time and fate that we have resolved to pave

the way for a grand peace for all the generations to

come by enduring the [unavoidable] and suffering what is

unsufferable. Having been able to save * * * and

maintain the structure of the Imperial State, we are

always with you, our good and loyal subjects, relying

upon your sincerity and integrity.

Beware most strictly of any outbursts of emotion that

may engender needless complications, of any fraternal

contention and strife that may create confusion, lead

you astray and cause you to lose the confidence of the

world.

Let the entire nation continue as one family from

generation to generation, ever firm in its faith of the

imperishableness of its divine land, and mindful of its

heavy burden of responsibilities, and the long road

before it. Unite your total strength to be devoted to

the construction for the future. Cultivate the ways of

rectitude, nobility of spirit, and work

with resolution so that you may enhance the innate

glory of the Imperial State and keep pace

with the progress of the world.

|

Emperor Hirohito's Surrender Rescript

to Japanese Troops

17 August 1945

TO THE OFFICERS AND MEN OF THE IMPERIAL FORCES:

Three years and eight months have elapsed since we declared war on the

United States and Britain. During this time our beloved men of the army

and navy, sacrificing their lives, have fought valiantly on

disease-stricken and barren lands and on tempestuous waters in the

blazing sun, and of this we are deeply grateful.

Now that the Soviet Union has entered the war against us, to continue

the war under the present internal and external conditions would be

only to increase needlessly the ravages of war finally to the point of

endangering the very foundation of the Empire's existence

With that in mind and although the fighting spirit of the Imperial Army

and Navy is as high as ever, with a view to maintaining and protecting

our noble national policy we are about to make peace with the United

States, Britain, the Soviet Union and Chungking.

To a large number of loyal and brave officers and men of the Imperial

forces who have died in battle and from sicknesses goes our deepest

grief. At the same time we believe the loyalty and achievements of you

officers and men of the Imperial forces will for all time be the

quintessence of our nation.

We trust that you officers and men of the Imperial forces will comply

with our intention and will maintain a solid unity and strict

discipline in your movements and that you will bear the hardest of all

difficulties, bear the unbearable and leave an everlasting foundation

of the nation.

[Seal of the Empire]

Signed: HIROHITO

Source: U. S. Govt. Imperial Rescript Granted the Ministers of War and

Navy. 17 August 1945. Reproduced in facsimile as Serial 2118, in

Psychological Warfare, Part Two, Supplement 2 CINCPAC-CINCPOA Bulletin

#164-45. 64-45.

|

See also these assorted photos and news clippings re the Investigation

of Emperor Hirohito for prosecution as war criminal. (Record

Group 153, Box 107, Folders 2 and 26)

TOP SECRET

ULTRA

Ambassador Sato's 20 July 1945 Message to Foreign Minister Togo

Japanís ambassador to the Soviet Union, Naotake Sato, sent

a telegram from Moscow to Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo on July 20,

1945. Note that Sato says his statements were "not in accord with the treasured communication from His Majesty,"

i.e. Sato's belief that Japan should surrender to the Allied Forces, to

preserve the lives of the people of Japan and their nation, especially

in view of the fact that Japan "had completely lost control of the air

and of the sea." This phrasing has been lost (deliberately deleted?) in

some transcriptions. (full document)

On Jan. 24, 1946,

MacArthur wrote a message to the Joints Chiefs of Staff regarding

the emperor:

He is a symbol which unites all

Japanese. Destroy him and the nation will disintegrate.

Practically all Japanese venerate him as the social head of the

State and believe rightly or wrongly that the Potsdam Agreements

were intended to maintain him as the emperor of Japan. They will

regard Allied action to the contrary as the greatest betrayal in

their history and the hatreds and resentments engendered by this

thought will unquestionably last for all measurable time. A

vendetta for revenge will thereby be initiated whose cycle may

well not be completed for centuries if ever.

The whole of Japan can be expected, in my opinion, to resist the

action either by passive or semi-active means..... It would be

absolutely essential to greatly increase the occupational

forces. It is quite possible that a minimum of a million troops

would be required which would have to be maintained for an

indefinite number of years.

The decision as to whether the emperor should be tried as a war

criminal involves a policy determination upon such a high level

that I would not feel it appropriate for me to make a

recommendation; but if the decision by the heads of states is in

the affirmative, I recommend the above measures as imperative. ( Original

document)

MacArthur's message regarding criminal action against the Emperor

Hirohito was handled the very next day. Here's from a blog posting

of mine:

February 10, 2010

MacArthur on Exemption of the

Emperor

from War Criminals, January 25, 1946

http://www.ndl.go.jp/constitution/e/shiryo/03/064shoshi.html

Documents

with

Commentaries Part 3 Formulation of the GHQ Draft and

Response of the Japanese Government

3-3 Telegram, MacArthur to

Eisenhower, Commander in Chief, U.S. Army Forces, Pacific,

concerning exemption of the Emperor from War Criminals,

January 25, 1946

The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, on November 29, 1945, ordered

MacArthur to gather information regarding whether the Emperor

had committed any war crimes. In response to this, MacArthur

sent a telegram dated January 25, 1946 reporting that there

was no evidence of the Emperor having committed any war

crimes. In addition to this, MacArthur stated that charging

the Emperor would cause confusion in the situation in Japan

thus requiring a longer occupation with increased military and

civilian personnel. He made it clear that he would prefer not

to charge the Emperor in consideration of the burden such

action would create for the United States.

| Actual Title of Source |

Incoming Classified Message From: CINCAFPAC Adv

Tokyo, Japan To: War Department |

| Date |

25 January, 1946 |

| Document Number |

State Department Records Decimal File,

1945-1949"894.001 HIROHITO/1-2546"<Sheet No. SDDF

(B)00065> |

| Repository (reproduction) |

National Diet Library |

| Repository |

U.S. National Archives & Records

Administration (RG59) |

| Note |

Microfiche |

In a review of a

book by Leonard Mosley on the Emperor of Japan, author David

Bergamini wrote:

In September

1945, the Japanese cabinet, in anticipation of Allied

demands, drew up a list of war criminals. Hirohito forthrightly

refused even to consider it because, he said, these were his

'most loyal retainers.' MacArthur needed the emperor untried and

unreviled. - LIFE

magazine, June 17, 1966

For further study into why Emperor Hirohito was not tried at the

Tokyo War Crimes Trials (IMTFE), see Victors' Justice: Tokyo War Crimes

Trial by Richard H. Minear (2015), pp. 138-145.

Another book that may be helpful, a rebuttal of sorts composed of

articles by scholars including Japanese, is Beyond Victor's Justice? The Tokyo

War Crimes Trial Revisited by Simpson, McCormack,

and Tanaka (2011). See also the section, "Why Hirohito Was Not

Tried," in War Responsibility

and Historical Memory: Hirohito's Apparition by Herbert

Bix (2008):

General Douglas MacArthur, before

he had even arrived on Japanese soil, assumed incorrectly that

Hirohito had been a mere figurehead emperor and a virtually

powerless puppet of Japan's "militarists." This helped the US

military to use him just as Japan's militarists had once done,

to ease their rule, legitimize reforms, and insure their smooth

implementation... Such occupation-sponsored myths strengthened

Japanese victim consciousness and impede the search for truth...

But when some of the judges on the Tokyo tribunal felt compelled

to call attention in their dissenting final judgments to the

emperor's total, unqualified political immunity from leadership

crimes even though he had launched the aggressive war, they

insured that the Hirohito case would be remembered.

One of these judges giving a dissenting opinion at the trial,

Justice Bernard of France, disagreed because the emperor was NOT

included in the list of those to be prosecuted, even though he

felt there was enough evidence to implicate the emperor.

Another individual brought out in prominence in this whole matter

is MacArthur's military secretary, Brig. Gen. Bonner Fellers. Here

is one excerpt, out of many possible, from Embracing

Defeat by John Dower (p. 297):

Had the imperial household been

privy to communications at the top level of GHQ, they would have

been ecstatic, for there was little fundamental difference

between their hopes and SCAP's intentions. On October 1,

MacArthur received through Fellers a short legal brief that made

absolutely clear that SCAP had no interest in seriously

investigating Hirohito's actual role in the war undertaken in

his name. The brief took as "facts" that the emperor had not

exercised free will in signing the declaration of war; that he

had "lack of knowledge of the true state of affairs"; and that

he had risked his life in attempting to effect the surrender. It

offered, in awkward legalese, the one-sentence "Conclusion" that

"If fraud, menace or duress sufficient to negative intent can be

affirmatively established by the Emperor, he could not stand

convicted in a democratic court of law." And it ended with the

following "Recommendation":

a. That in the interest of

peaceful occupation and rehabilitation of Japan, prevention of

revolution and communism, all facts surrounding the execution

of the declaration of war and subsequent position of the

Emperor which tend to show fraud, menace or duress be

marshalled.

b. That if such facts are sufficient to establish an

affirmative defense beyond a reasonable doubt, positive action

be taken to prevent indictment and prosecution of the Emperor

as a war criminal.

On the next day, General Fellers prepared a long memorandum for

MacArthur's exclusive perusal that spelled out in richer detail

why it was imperative that such mitigating "facts" be marshaled.

Fellers's memo was written before SCAP's "civil liberties"

directive, before free discussion existed in Japan, before

political prisoners had been released from prison, before the

most basic questions of "war responsibility" had been clearly

formulated, before trends in popular sentiment had been

seriously evaluated, before it was even legal for Japanese to

speak such phrases as "popular sovereignty." It read, in full,

as follows:

The attitude of the Japanese

toward their Emperor is not generally understood. Unlike

Christians, the Japanese have no God with whom to commune.

Their Emperor is the living symbol of the race in whom lies

the virtues of their ancestors. He is the incarnation of

national spirit, incapable of wrong or misdeeds. Loyalty to

him is absolute. Although no one fears him, all hold their

Emperor in reverential awe. They would not touch him, look

into his face, address him, step on his shadow. Their abject

homage to him amounts to a self abnegation sustained by a

religious patriotism the depth of which is incomprehensible to

Westerners.

It would be a sacrilege to entertain the idea that the Emperor

is on a level with the people or any governmental official. To

try him as a war criminal would not only be blasphemous but a

denial of spiritual freedom.

The Imperial War Rescript, 8 December 1941, was the

inescapable responsibility of the Emperor who, as the head of

a then sovereign state, possessed the legal right to issue it.

From the highest and most reliable sources, it can be

established that the war did not stem from the Emperor

himself. He has personally said that he had no intention to

have the War Rescript used as Tojo used it.

It is a fundamental American concept that the people of any

nation have the inherent right to choose their own government.

Were the Japanese given this opportunity, they would select

the Emperor as the symbolic head of the state. The masses are

especially devoted to Hirohito. They feel that his addressing

the people personally made him unprecedentally close to them.

His rescript demanding peace filled them with joy. They know

he is no puppet now. They feel his retention is not a barrier

to as liberal a government as they are qualified to enjoy.

In effecting our bloodless invasion, we requisitioned the

services of the Emperor. By his order seven million soldiers

laid down their arms and are being rapidly demobilized.

Through his act hundreds of thousands of American casualties

were avoided and the war terminated far ahead of schedule.

Therefore having made good use of the Emperor, to try him for

war crimes, to the Japanese, would amount to a breach of

faith. Moreover, the Japanese feel that unconditional

surrender as outlined in the Potsdam Declaration meant

preservation of the State structure, which includes the

Emperor.

If the Emperor were tried for war crimes, the governmental

structure would collapse and a general uprising would be

inevitable. The people will uncomplainingly stand any other

humiliation. Although they are disarmed, there would be chaos

and bloodshed. It would necessitate a large expeditionary

force with many thousands of public officials. The period of

occupation would be prolonged and we would have alienated the

Japanese.

American long range interests require friendly relations with

the Orient based on mutual respect, faith and understanding.

In the long run it is of paramount, national importance that

Japan harbor no lasting resentment.

SCAP's commitment to saving and using the emperor was firm. The

pressing, immediate task was to create the most usable emperor

possible.

Furthermore, Japanese defendants in the trials were compliant in

not mentioning anything which would incriminate the emperor; from

p. 325 in Dower's work:

Before the war crimes trials

actually convened, SCAP, the IPS, and Japanese officials worked

behind the scenes not only to prevent Emperor Hirohito from

being indicted, but also to slant the testimony of the

defendants to ensure that no one implicated him. Former admiral

and prime minister Yonai, following Fellers's advice, apparently

did caution Tojo to take care not to incriminate the emperor in

any way. The collaborative campaign to shape the nature of the

trials went considerably beyond this, however. High officials in

court circles and the government collaborated with GHQ in

compiling lists of prospective war criminals, while the hundred

or so prominent individuals eventually arrested as "Class A"

suspects and incarcerated in Sugamo Prison for the duration of

the trial (of whom only twenty-eight were indicted) solemnly

vowed on their own to protect their sovereign against any

possible taint of war responsibility. The sustained intensity of

this campaign to protect the emperor was revealed when, in

testifying before the tribunal on December 31, 1947, Tojo

momentarily strayed from the agreed-on line concerning imperial

innocence and referred to the emperor's ultimate authority. The

American-led prosecution immediately arranged that he be

secretly coached to recant this testimony.

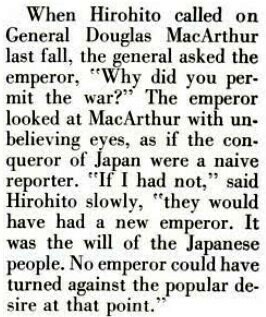

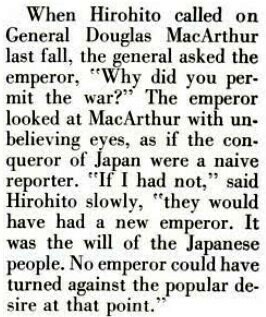

Why Hirohito permitted the war: "It was the will of the Japanese people"

|