June 14 -- Flag Day Special June 14 -- Flag Day Special

FLAGS

OF

OUR POW FATHERS

"Gaunt allied prisoners of war at Aomori [Omori] camp near Yokohama

cheer rescuers from U.S. Navy, waving flags of the United States,

Great Britain and Holland." Japan, August 29, 1945

The American flag is perhaps the most widely displayed flag in the world,

not only on flag poles, but on caps, backpacks, T-shirts, towels, coffee

mugs, shopping bags and scores of other items. To many it seems like just

another piece of merchandise.

But to thousands of men nearly 60 years ago, it was one of the most beautiful

sights they had ever seen. And they cried, unable to contain the joy in their

hearts -- their dream had come true.

I'd like to share with you on this

Flag

Day a few stories of the flags our POW fathers made at the end of

their captivity in prison camps in Japan. To them those flags were more than

just pieces of colored cloth and silk -- they were symbols of something very

dear to their hearts...

...symbols of home, their loved ones, their country they still served, and

the liberty and freedom they were now finally able to enjoy after 3½

years of being deprived of that which they so much yearned for.

It is no wonder then what strong emotions these simple pieces of cloth evoked!

And no wonder those surviving POWs to this day count it such a great blessing,

honor and privilege to have and enjoy the freedoms -- freedoms we take so

much for granted -- in a nation God has so uniquely blessed in His providence.

Clayton Dahl

Fukuoka #3, Kokura

August 1945. Japan. A liberated camp. Some of the boys got some materials,

red, white and blue, and they found a sewing machine and made a huge American

flag -- at least 20 feet by 15 feet.

My, how beautiful! They raised the flag on the flagpole and all the camp

came to see. Somebody got a bugle and they played taps for our dead buddies.

Oh, if only all Americans would know what it is like not to see our beautiful

flag for three and a half years.

Words

of War -- Fresno woman grasps late husband's story as a POW through his diary

of pain, triumph

Rodney

Kephart

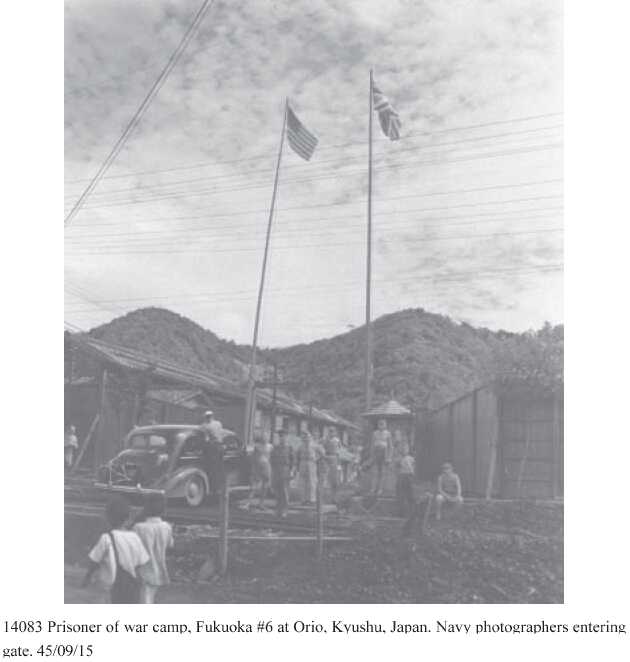

Fukuoka #6, Mizumaki

On the morning of September 1, 1945, the day before the signing of the Japanese

surrender, senior American officers who were also prisoners in the camp came

to Kephart and fellow prisoner Ryland Barnett with the parachute silk from

the food drop. Knowing their liberation was near, the officers asked the

men to sew an American flag.

Since he was the only one who knew how to operate the camp's old Japanese

sewing machine, Kephart went straight to work. He and Barnett started the

flag at 10:00 a.m. and didn't quit sewing for more than 16 hours. In the

early hours of the next morning, with the flag completed, Kephart fell into

his bunk and slept. As dawn crept over the eastern sky, he was too worn out

to get up. But he heard the reveille bugle and cheering prisoners as his

flag was raised over the No. 6 prison camp in Orio, Fukuoka, Japan, at the

same time the Japanese signed the surrender.

"I just rolled over in my bunk and started sobbing," he said. That moment

marked the end of 45 agonizing months as a prisoner of war, making Kephart

one of the longest-held prisoners of World War II. His flag flew proudly

over the prison camp for 11 days until he and the camp's other 1,700 American

and Allied prisoners were rescued.

Capt. Jerome McDavitt

Hiroshima #6 (Omine)

About two or three minutes to twelve o'clock everybody was out to watch the

drop. Off to the east, in a beautiful blue sky containing two huge white

fleecy clouds, someone saw a speck. As it got bigger and we heard the buzz,

we saw there were two planes coming directly toward us between the clouds.

As they crossed overhead, they waved their wings. Their bomb bays, I noticed,

were still closed. They went on over and made a big left-hand turn and came

back between those two clouds again; this time the bomb bay doors were wide

open. From them they kicked out, each of them, twenty-foru double-deck fifty-five

gallon drums, welded and stacked. They floated down to us on sixteen red

parachutes, sixteen white parachutes, and sixteen blue parachutes. No reason

I can think of, except it was to show which the Air Force unit that made

the drop wanted to give us. I stood there amazed, and whatever words you

want to use would describe my feelings.

Several

of the men ran over to me. "Captain, sir." I didn't fuss at them, but I thought,

"You know, that's the first time you've referred to me as 'sir' in three

and a half years." I said, "Yes?" "Captain, sir, can we make one?" I didn't

want them to think I'd already figured it out, so I paused. Finally, I said,

"Yes, but be careful you don't tear the parachutes." Several

of the men ran over to me. "Captain, sir." I didn't fuss at them, but I thought,

"You know, that's the first time you've referred to me as 'sir' in three

and a half years." I said, "Yes?" "Captain, sir, can we make one?" I didn't

want them to think I'd already figured it out, so I paused. Finally, I said,

"Yes, but be careful you don't tear the parachutes."

The next morning an American flag was flying over our camp.

-- Death March -- The Survivors of Bataan

by Donald Knox

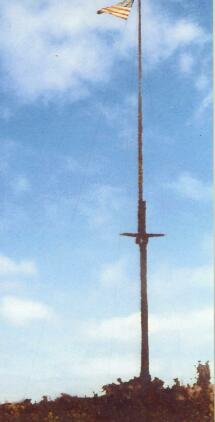

Note from Linda McDavitt, daughter:

"Enclosed is a picture of the flag made at Omine-machi upon liberation. There

is a story from a book and a picture of the men. The color photo was computer

enhanced from a black & white that we were told was a picture of the

flag flying after it was made. The black & white was at some reunion

and I assume that along with my grandmother, Dad, and Ben Guyton, the rest

of the men also were in Omine-machi and helped make the flag. The flag is

now housed at Texas A&M in College Station in the Alumni Center."

Baselio "Joe" Zorzanello

Sendai #6, Hanawa

After the surrender, the Japanese soldiers killed some American soldiers

"for no reason," according to Zorzanello. The worst thing he can recall was

the desecration of the American Flag.

Seeing the flag ripped apart and defiled made him feel naked, he said. "That

flag meant a lot to us, and to see them treat it like dirt really hurt."

The first night as prisoners, Zorzanello and the other men slept directly

on the hot sand. There were no blankets.

He said the flag desecration had a terrible effect on him.

"I had a nightmare that I was back in Massachusetts, where I was born," he

said. "I'll never forget it."

He described the nightmare as follows: "It was winter and there was a blizzard.

I was sleeping in the attic, with wind blowing the snow through. I was terrified,

and I went to my mother. I was broken hearted and demoralized. She tried

to comfort me.

"[When] I woke up, I didn't want my mother involved [in this war]. I was

a grown man, and I'd have to take care of myself. Physically, I was freezing

while lying on the hot sand.

"I guess my body had reacted to the dream. My skin was so cold. That's the

one thing through the entire war I couldn't cope with. [The nightmare] was

very traumatic," he said.

Veteran

recalls experiences in WWII

Otto Erler

Nagoya #1, Kamioka

"Otto was definitely a very blessed man. I think his would make a good story

for a lot of Americans," he said. "We can get through life without giving

up."

Otto Erler died quietly in his sleep in 1967 after 46 hard-lived years, but

Bud Erler and Bill Strouse have remained committed to his memory, visiting

those who served alongside Cpl. Erler and preserving the tale of the flag

for future generations.

Bud Erler faithfully wears a flag pendant as a reminder of his uncle.

"It says this is my family. This is where I come from," he said. "(The flag)

was a piece of America he held on to and he didn't give up."

For Mr. Strouse, a dream came true when he recently arranged to view Otto

Erler's flag at the Dallas Historical Society, where it was donated upon

the end of World War II.

"It was just fantastic. It was hard to believe it. I had heard so much about

it," he said. "The flag, as a symbol, means a heck of a lot to me, as it

does anyone in the military."

Former POW Mr. McDowell couldn't agree more.

"It meant a great deal to us - to our spirit. Spirit was what we lived on,"

he said. "It was one of a kind -- Otto and his flag."

Long,

great story about a WWII POW and his flag

"Prisoners of war possessed limited items of clothing, personal effects,

and field gear. Going through the packs and pouches, I noticed a thick lining

slightly sticking out at the bottom. I pulled it out, paying little attention

to the pack it was in. The item concealed a slit, purposely cut in the lining

of the pack."

Inside the pack was the POW flag that is now on display in our Americanism

Museum. Ill. Delsi surmised, "The flag must have been a source of courage

and strength to someone or to some group of Americans." While his assessment

is true, the flag continues to be a source of courage to generations of American

heroes.

Recently

rediscovered WW II POW flag

Col. Ralph T. Artman

Hiroshima #4, Mukaishima

Seven years ago a Fort Knox colonel stood in a Japanese prisoner of war camp

and watched misty-eyed as the rising sun emblem was struck from the flagstaff

and Old Glory went up in its place.

It was a crudely-sewn flag pieced together from parachute cloth, its stars

cut out jaggedly by sewing-kit tools and tin cans. But to the jubilant internees

who had labored to make it in the first few hours after word came of

Japan's surrender, craftsmanship was unimportant.....

He remembers how the men eagerly marked out their area with large letters

"POW" so that it could be seen from the sky. American planes began dropping

food and medical supplies ... red, white and blue parachutes floated down

on Mukaishima.

In those first frantic moments of freedom, the ex-prisoners realized they

had no American Flag. Col. Artman suggested making one from the parachutes.

"There was no means of sewing together the stars and stripes even after the

patterns were cut. Since the Americans were in command of the situation at

that time, I 'commandeered' the three local Japanese tailor shops to do the

sewing after Americans cut out the part according to rough specifications.

"We had the three tailor shops working constantly (and reluctantly) throughout

all of one night in order to have the flag ready as soon as possible. At

approximately 11 a.m. on the morning of Aug. 18, 1945, we lowered the Japanese

flag which had been flying over the camp and its place raised our American

flag.

"As the American flag was raised, we had a brief ceremony for the remaining

time we were there, our improvised American flag flew over the camp. I do

believe it is the first American flag raised on Japanese soil after the cessation

of hostilities."

"A lot of men lived and died dreaming of the day they'd see these colors

flying again."

First

To Fly Over Japan; Historic U.S. Flag Going to Museum

Some

men will never forget 'Bataan'

Carl S. Nordin

Nagoya #5, Yokkaichi

Life in prison camp was difficult, tedious and boring. After a couple of

years, the Japanese allowed a few musical instruments in camp. Naturally,

in a group of 2,000 men, there is considerable talent, so with these instruments,

a Corporal Biggs developed an entertainment troupe. Soon they were developing

USO-type programs. But there was barely room enough between the barracks

to accommodate an audience. Over a period of time, the Japanese had come

to realize this as a good way to keep the prisoners from becoming restive.

As the popularity of the troupe, and the confidence of the Japanese increased,

they were finally able to convince the Japanese to put on a full-fledged

program.

One condition was necessary, however. The Japanese would preview the program

before it was put on for the troops. This preview would be in the hospital

area. That way the sick could see it along with the Japanese, and with the

added benefit of shade for the viewers. The performance for the rest of the

camp would be out in the hot sun of the parade ground, where a stage had

already been erected for the use of the Japanese camp commander for his annual

(Pearl Harbor Day) reading of the Imperial Rescript. And for other occasional

diatribes. Programs were varied, but usually consisted of short skits, comedy

acts, a unique whistling act, and musical numbers of various kinds.

At the close of each program everyone would join in singing "God Bless America".

This went on for several months; the content was no different than before;

but at the performance out on the parade ground (where there were no Japanese

present), and at the close of the performance with everyone singing "God

Bless America", Corporal Biggs and Chief Bo'sun Regan stepped to the front

of the group as Chief Regan reached inside his denim jacket and began pulling

out the American Flag, and - handing one end to Corporal Biggs - they held

up the flag of the "41 Boat" for all to see, bullet holes and all!

Never have I heard "God Bless America" sung with more gusto and feeling as

those several hundred hard-bitten men stood out there in the hot sun, and

belted it out at the top of their lungs. For there before them was the flag

of our country, for which we had fought and sacrificed, and which we had

not seen in over two years. In all that group of men, I doubt there was one

dry eye as we viewed the symbol of the greatest country on earth.

Although this event occurred almost sixty years ago, and half a world away,

even to this day, when I see that flag or hear that song, I am overtaken

with a special feeling of awe and gratefulness.

A True Flag

Story

Pete George

Tokyo #12, Mitsushima

And the irony of that was that when they organized the new 4th division,

they took the flag and the standard which is a Marine Corp flag and kept

them covered and encased. They made a vow that they would not uncase those

colors until they came to Japan and liberated all of the 4th mariners and

throw a big parade for us, and that was what they did. They unfurled those

colors and I think that you could hear the uproar back in the States, you

know. And they went through that parade for us and everything. Well, you

cried really. Just no way that you could hold it back, you know.

http://www.chinamarines.com/docs/men_PG6.htm

Otto Erler

Nagoya #1, Kamioka

Not many of us have seen the colors struck. No, not retired. Not simply lowered

at the end of the day, but deliberately pulled down. World War II Marine,

Otto Erler, did from his foxhole on Corregidor.

Knocked unconscious by a Japanese mortar shell, Erler came too just as Japanese

troops swarmed over him. Corregidor had fallen. As Erler looked up past a

Japanese bayonet, up the barrel of the weapon, and over the shoulder of his

captor . . . he saw a tattered "Old Glory" coming down. In his head were

the words of a poem: "A moth-eaten rag on a worm-eaten pole. It doesn't look

likely to stir a man's soul . . ." But it did. Oh, how it did stir Erler's

soul. In that flag he saw America folding, America coming down. And that

20-year-old Marine from Dallas, Texas cried.

Later, under guard on a dock in Manila, enroute to a prisoner of war camp,

Erler snuck away into a small, empty office building on the pier, in search

of - of all things - toilet paper. In rummaging through the place, he found

none. But in a corner, in a dark closet, he found an American flag. It grabbed

him by the throat . . . it was a piece of home. It was something he could

have faith in. He didn't stop to think that prisoners were shot for less.

He snuck back into the ranks of prisoners and quickly hid the flag in his

duffel bag. Transported on prisoner ships, Erler kept the flag hidden, and

for the first time brought it out for a comrade's burial at sea. Done with

permission from his captors, Erler's flag draped the lead-filled, canvas

body bags of several who died on the trip.

When leaving the transport and heading to a more permanent camp, Erler was

able to smuggle the flag off the ship. He carried it with him and kept it

in his pillowcase. Eventually it was found and taken from Erler who, with

the ranking American officer, bravely told the Japanese as he handed it over,

"This is an American flag. We expect it to be treated with proper courtesy

and to be returned when we leave."

They reluctantly agreed, but not without penalties: rations would be halved

for thirty days, no cigarettes, and lights out at 9:00 p.m. In early 1944

Erler was transferred to a lead mine in Japan. As he prepared to depart,

he bravely asked for the return of the Flag. It was given over to him.

At the lead mine he was allowed to keep his flag, but only for burials. For

use in any other way, he would be held responsible. It found use ten times

in sixteen months. Then in August of 1945, after more than three years as

a POW, peace was at hand. The war was over and it was Erler's turn to strike

the colors. Down came the rising sun and up went the Stars and Stripes.

Through his years as a prisoner, Erler's flag buried 25 men and raised the

spirits and gave hope to thousands. That 42-star flag is still around. It

resides at the Dallas Historical society. It is tattered and torn. It's one

of those things best described by British General Sir Edward Bruce Hamley:

"A moth-eaten rag on a worm-eaten pole,

It doesn't look likely to stir a man's soul;

'Tis the deeds that were done 'neath the moth-eaten rag

When that pole was a staff and the rag was a Flag."

The

Story of Otto Erler, WWII POW

From The American Legion Magazine,1960

Abel F.

Ortega

Osaka #10, Maibara

You know my dad, Abel F. Ortega. He had 4 flags made from B-29 parachutes

at Camp Maibara, Japan. Since he was the camp artist, he was selected to

draw the flag designs and then have them made. He took the drawings and the

material to a Japanese tailor in Maibara and told him he had 3 days to make

the flags. It was the American, British, Austrailian, & Dutch flags.

Roger Mansell has a picture of the Camp and the

flags

flying at the main gate.

Abel Jr.

Martin

Christie

Tokyo #8,

Hitachi

"Page 67, Vol.1, Defenders of Philippines, Guam and Wake Islands

(Turner) shows the American group and the US Flag made from parachute

material. Two other flags were made, an Indonesian and a British. I have

heard that Captain Short, Hitachi Camp Commander, presented the US Flag from

Hitachi to the Truman Library and it was on display at one time."

Betsy Herold Heimke

Bilibid, Philippines

Though this page deals with the men who made flags, I found this about a

young girl named Betsy, not unlike that famous flag-maker back in 1776,

Betsy Ross:

We like to give credit to our speakers who are active in their communities

and in their schools. Betsy Herold Heimke, a member of the Heart of America

AXPOW Chapter in the Greater Kansas City area, is an active speaker with

an unusual story to tell.

Betsy's parents, Elmer and Ethel Herold were teaching school in the Philippines

when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Later that day, the Herolds heard

bombs exploding in their area of the Philippines. Twenty days later about

40 Japanese soldiers knocked on the Heralds' door in the middle of the night

and told them to attend a meeting in the morning to register. They went to

the meeting and never returned home. Betsy was 12 years old.

Betsy and her family ended up in the Bilibid Prison in Manila. The prison

conditions were unbelievably bad. Little food, no plumbing and the stench

was sickening. The U.S Army's 37th Division liberated the camp in February

1945. Of the 500 civilians at Bilibid, 456 survived. Betsy returned to the

US, finished her schooling, and earned a nursing degree from Northwestern

University in 1952. She later met and married Karl F. Heimke, a B-26 pilot

flying in the ETO.

When Betsy tells her "Prison Camp Stories" she is amazed that many Americans

did not know that the Japanese incarcerated civilians during WWII. Her listeners

are in awe when she tells her experiences (as a teenager) under such deprived

conditions.

While incarcerated at Bilibid, Betsy made a small American flag. The flag

is now framed and protected by a glass cover. She takes the flag with her

when she speaks to schools and civic clubs. At a recent talk to the Daughters

of the American Revolution's 106th annual conference, Betsy writes, "When

I showed them my framed little American flag their tearful and standing ovation

made me cry. I was really overwhelmed."

http://www.axpow.org/education.htm

Harvey Boatman

Burma

Three days before the Japanese surrendered, Boatman's appendix ruptured.

A Dutch doctor, on his deathbed, instructed Boatman's comrades on how to

use a bayonet to remove the appendix. Six men held Boatman down for the amateur

surgery. The doctor died the next day.

Once the Japanese surrendered, Boatman sewed a U.S. flag using a small,

pedal-operated sewing machine that someone had found near the prison camp.

He cut cloth with the same bayonet that had been used to remove his appendix.

That flag flew over the prison compound and now sits in glass at an Army

Reserve center museum in Witchita Falls.

Survivor's

friends, strength got him through illnesses

Conrad G.

Russell

Osaka #6, Akenobe

"There was a flag made at Akenobe 6-B. I have a photo of it. My uncle,

Conrad G. Russell, USMC, was there." -- Jeff Russell

The sudden actual ending of the war was so surprising that we may have been

caught "off guard". The next morning things began to happen. A 'limey' p.o.w.

whom we called Harry, stepped into our building. He had an old battered pillow

which he'd managed to hang onto from his time, four years ago, in Hong Kong.

He told us that many times during the Jap's surprise shakedowns, that old

pillow had been pummeled as guards searched for any hard object(s). This

day, Harry ripped open a seam and pulled out a beautiful Union Jack, about

six feet long. A cheer went up from everyone in the building! He had managed

to secret the flag and carry it with him since the fall of Hong Kong. (Our

camp was composed of about half British and Aussies and half Americans.)

What a dilemma! We must have an American flag, so the only thing to do was

to make one. Scrounging around we came up with enough material for the stars

and stripes but no blue for the flag's field. One of the guys told of a 'limey'

in the so-called medical ward who wanted to contribute a blue shirt that

he had secreted away. He mst have had grand plans for the use of that shirt,

but decided it could be better used here. We thanked him profusely but had

nothing to give him in return, which we wanted to do. What we did do was

assure him, and the other sick, was that upon making contact with rescuers,

we would give them a map that would send them directly here for their rescue.

(At the end, it did work out, just that way.) A couple of guys worked on

it's crude construction but when they were finished, we were proud of it.

We planned to have a flag-raising service the next morning. The morning dawned

beautiful and the sunrise was just perfect! The American flag and the Union

Jack, from Hong Kong, were raised simultaneously. It's a memory which I and

the other survivors, who were there, will cherish for as long as we live!

The Limey's and Aussie's sang "God Save the King", then the Americans sang

"The Star Spangled Banner". We were located at a high altitude, anyway, but

as the flags were raised, I felt at a higher level still -- as though I could

look down on all the Japanese cities, even the Imperial Palace.

My husband and I attended the Western States Chapter of the ADBC convention

in Ventura a few months ago. We brought Mr. Jay Rye, a veteran along with

us to the convention. Mr. Rye was on the same hellship (the Noto Maru), and

the same last two POW camps as my dad (Sgt. George P. Nord) in Japan. These

two camps were Omori and Sendai 10D.

During the trip, Mr. Rye shared several stories with us. He was a pleasure

to be with. One of his stories had to do with the men making a flag at Sendai

10D. He said he wasn't sure where they found the sheets and paint, but both

an American flag and a British flag were made. There was some discussion

between the American and British officers as to whose flag would wave to

the right. Mr. Rye said he thought to himself, here the war is ended and

we're going to have WWIII over the flag waving. This was an indication of

just how proud the men were of their respective countries.

In the end, the American officer won because there were twice as many Americans

in the camp as British.

If you can confirm this story, that would be great.

Respectfully,

Greta A. Janz

Daughter of George P. Nord

20th Air Base, 27th Material Squadron

Survivor of Bataan, hellships and several POW camps

It would be easier to name a camp where NO flag was made. At

Rokuroshi,

one of the men had hidden a full size American flag for the entire war and

pulled it out the minute he learned the war was over. It was flying within

minutes.

The Yanks made flags at

Hirohata

and at

Maibara.

Take a look at the Hirohata pages. The one from Rokuroshi is in the lobby

of the capitol building for New York in Albany.

Roger Mansell

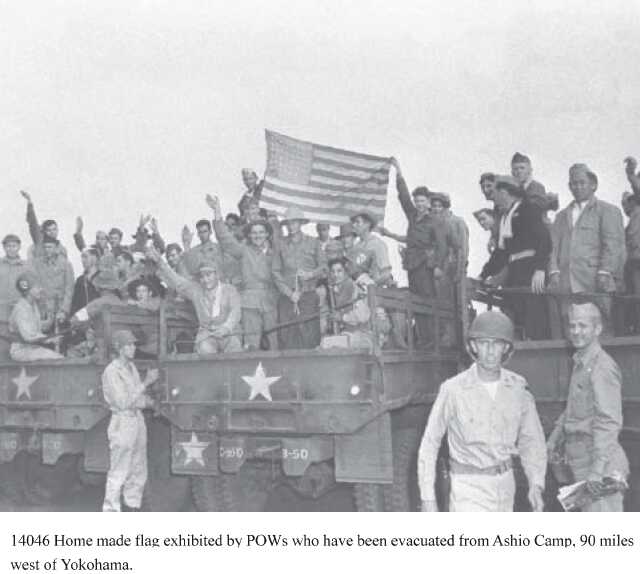

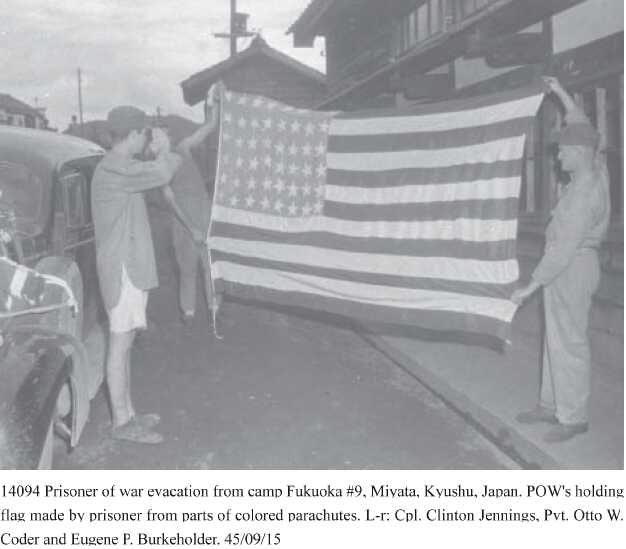

Tokyo #9, Ashio

Fukuoka #9, Miyata

"Oh, if only all Americans would know what it is like not to see our beautiful

flag for three and a half years."

Back to Update Page

|