| Fukuoka POW Camp #14 Saiwai, Nagasaki |

Main Index Main Camp List

| Fukuoka 14-B

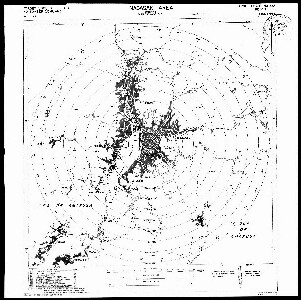

"Nagasaki" Location: NAGASAKI-shi, SAIWAI-machi Camp was 1850 meters (1.15 miles) from ground zero and was completely destroyed by the A-bomb.  Map Courtesy of US Merchant Marine Assn Satellite map (small memorial plaque on roadside (new location); site of new memorial) Aerial (Nov. 1947; courtesy of Japan Map Archives) Area map - relation to other Fukuoka area POW camps Employer of slave laborers: MITSUBISHI JUKOGYO NAGASAKI ZOSEN-JO [Mitsubishi Foundry Co.] History: 22 Apr 1943: Established as Fukuoka 14B Sept 1945: Rescue effected Time Line: Source: Henk Beekhuis - Dutch POW 25 April 1943: Group arrived (about 300 Dutch) 15 May 1943: Group arrived (two Dutch nurses) ex Fukuoka #2. Included the Dutch medics, Dr Huisman and nurses Charles Alexander Denkelaar and Schenkhuizen. 28 August 1943: Group arrived (12 men coming from Moekden/Mukden?) 4 Dec 1943: British known to have arrived ex Singapore per Bryer affidavit - Hawaii Maru (Maru Shichi (7) per Michno's book, "Death on the Hellships") 24 March 1944: Group arrived (2 Americans, Lowe and Van Allen, liberated at FUK-05) from the Kenwa Maru 25 June 1944: Group arrived (about 200 survivors of the Tamahoko Maru) Known facts: Survivors of Tamahoko Maru, sunk 24 June 1944, taken to this camp; not all survived. Tamahoko Maru carried 772 POWs, 560 perished. Report of British & Australian survivors ref the sinking of the Tamahoko Maru British POW Ronald Edwin Bryer: article #1, #2 George Duffy's Camp Description |

Labor:

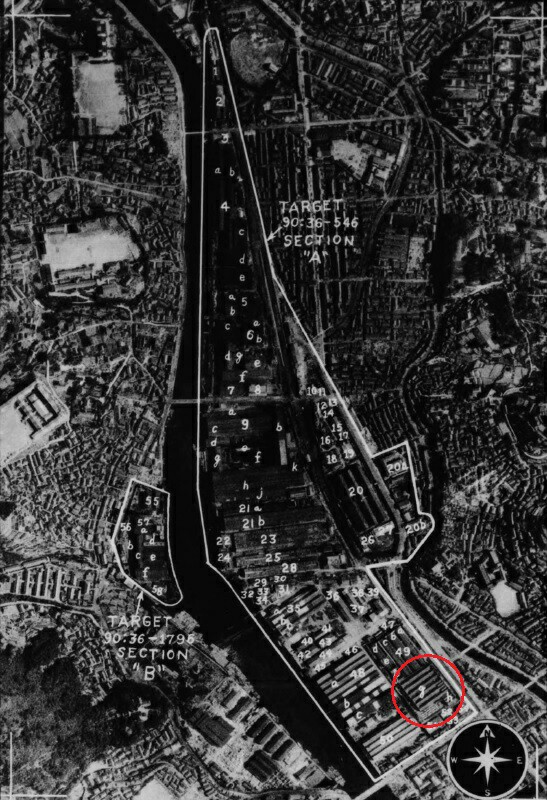

Iron Foundry, Mitsubishi Steel Works The POWs were used by Mitsubishi Heavy Industry Company. For full PDF report in Japanese, see here under 長崎三菱造船分所. (Special thanks to the POW Research Network of Japan) Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works target report (USSBS) - Note that the aerial photo shows the camp buildings but it was unknown to our military at the time (see below for photo, camp site circled in red). Note also this excerpt of the intel we had in late 1944 regarding POW camps in the Nagasaki area via interrogations of Japanese POWs. Hellships: Dutch arrived from Singapore on the Hawaii Maru, landing in Moji per Ronald Scholte. Rosters: Total = 195 POWs (152 Dutch, 24 Australian and 19 British; 113 deaths, 7 of whom were killed by atomic bomb) FUK-14 Rosters 1946-02-16 See also Henk Beekhuis' website (in Dutch) for info on #14 including rosters (Naamlijsten, per camp and alphabetical). Deceased: POW Research Network Eye Witness Report: Javanese/Dutch POW excellent description of atom blast and camp. Memorial monument - Completed on May 4, 2021 (YouTube video). See Foundation Monument Nagasaki for more information (site is in Dutch). Books: The Forgotten Highlander by Allistair Urquhart A Doctor's Sword by Bob Jackson (video) Nagasaki: The Forgotten Prisoners by John Willis (2022) At 11.02am on 9 August 1945,

America dropped the most powerful atomic bomb yet developed on

the Japanese port city of Nagasaki. The most European city in

Japan was flattened to the ground "as if it had been swept aside

by a broom." More than 70,000 Japanese were killed. As the bomb

dropped, hundreds of British, Australian, American, and Dutch

prisoners were working as forced labourers close to the weapon's

detonation point. This is their hidden history.

The men had already endured an extraordinary lottery of life and death. They had lived through nearly four years of malnutrition, disease, and brutality. In one of the greatest survival stories of the Second World War, the book traces the remarkable experiences of the prisoners back to the bloody battles in the Malayan jungle, before the dramatic fall of Fortress Singapore, the mighty symbol of the British Empire ,and then surrender in Java. Their lives grew ever more perilous when thousands were shipped off to build the infamous Thai-Burma Railway, including the Bridge on the River Kwai. If that was not enough, many were transported to Nagasaki and elsewhere in Japan in what were called hell ships. These ancient, hugely overcrowded vessels were regularly sunk by Allied submarines, leaving thousands of survivors adrift in the ocean for days. Then, some still had to endure their final supreme test, the world's second atomic bomb. Despite the horrors they faced, this is a story of resilience, comradeship, and hope. Using unpublished and rarely seen notes, interviews and memoirs, this unique book weaves together a powerful chorus of voices to paint a vivid picture of endurance and survival against terrifying odds. |

|||

Air Raids and Atomic Bombing of

Nagasaki

|

||||

|

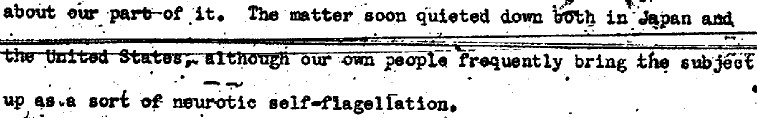

Secretary

of War Henry Stimson and the Least Abhorrent Choice

An excerpt from TIME Magazine, Feb. 3, 1947, "LEAST ABHORRENT CHOICE" ...The committee [a panel of four scientists set up to keep the President advised] considered giving the Japanese a demonstration "in some uninhabited area" in the hopes of frightening them out of the war. The idea was rejected. The demonstration might be a dud. "Nothing would have been more damaging to our effort to obtain surrender." The scientists agreed: "We see no acceptable alternative to direct military use." Henry Stimson searched his soul. Japan "must be administered a tremendous shock." Otherwise, "only the complete destruction of her military power could open the way to lasting peace." He compiled a tally of debits and credits in property and in human relationships and human lives: The Allies were faced with the task of destroying an armed force of 5,000,000 men and 5,000 suicide aircraft. Without the atomic bombs, a total of 5,000,000 Americans would have to be committed to a Japanese invasion. "Operations might be expected to cost over a million casualties to American forces alone... Enemy casualties would be much larger." Resistance would be fanatical. It would be necessary to leave the Japanese Islands "even more thoroughly destroyed" than Germany. Continued B-29 fire raids would wreak more damage than any atomic raids. But "the atomic bomb was more than a weapon of terrible destruction; it was a psychological weapon." It was Harry Truman who had to make the final, terrible decision. But "the ultimate responsibility for the recommendation to the President rested upon me, and I have no desire to veil it." ..."As I look back over the five years of my service as Secretary of War, I see too many stern and heart-rending decisions to be willing to pretend that war is anything else than what it is. The face of war is the face of death... This deliberate premeditated destruction was our least abhorrent choice." |

A-bomb targets and authorization, July 25, 1945

"Letter received from General Thomas T. Handy to General Carl Spaatz authorising the dropping of the first atomic bomb. Japan" - United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS)

Air raids on Nagasaki before the Atomic Bomb raid

Records nearly 20 air raids (over 210 aircraft) by the 20th (B-29's), 7th, 5th Air Forces and Navy planes, from August 1944 until Aug. 9, 1945. Included is a list of some of the American B-29 airmen captured by the Japanese on Aug. 20, 1944, on Iki Island in Nagasaki Pref. (see Japan POW Research Network PDF under "Seibu Kyushu District"; for full report, see MACR 42-24474). Air strikes continued on Japan even after the A-bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

Were the Japanese warned?

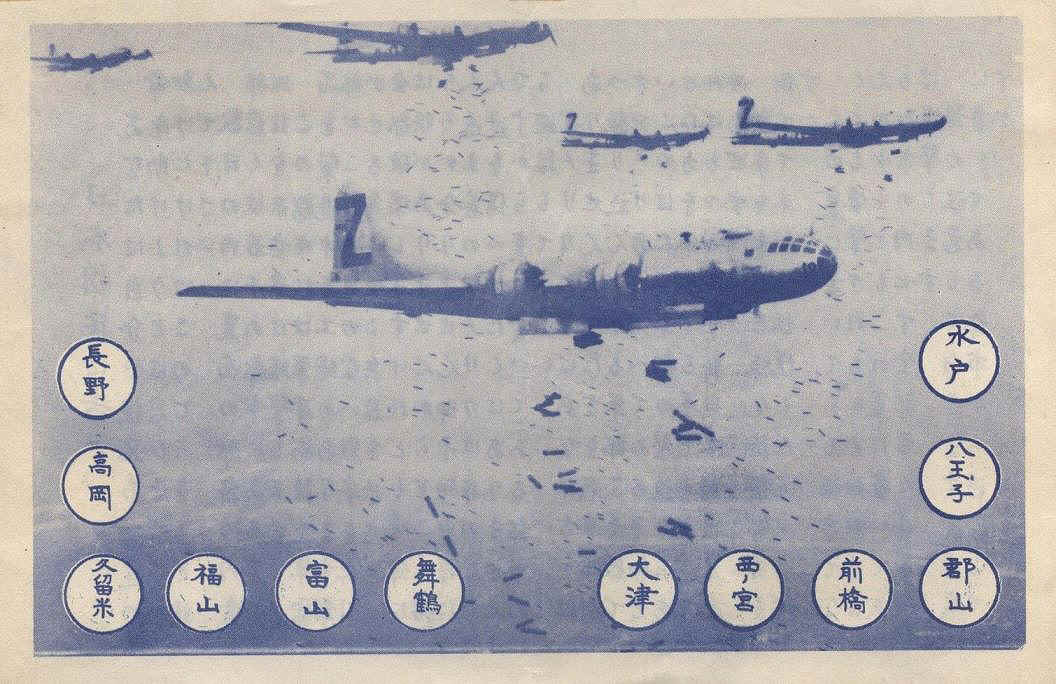

On Aug. 1, 1945, some 1 million leaflets were dropped on 30+ cities (including Nagasaki) telling them to flee the cities before bombs rained on them. By Aug. 9, The number of leaflets dropped over major cities in Japan warning them about the A-bomb had reached some 5 million. - Williams Info War in Pacific

Nagasaki warned to evacuate (leaflet in Japanese with English translation, Aug. 6, 1945)

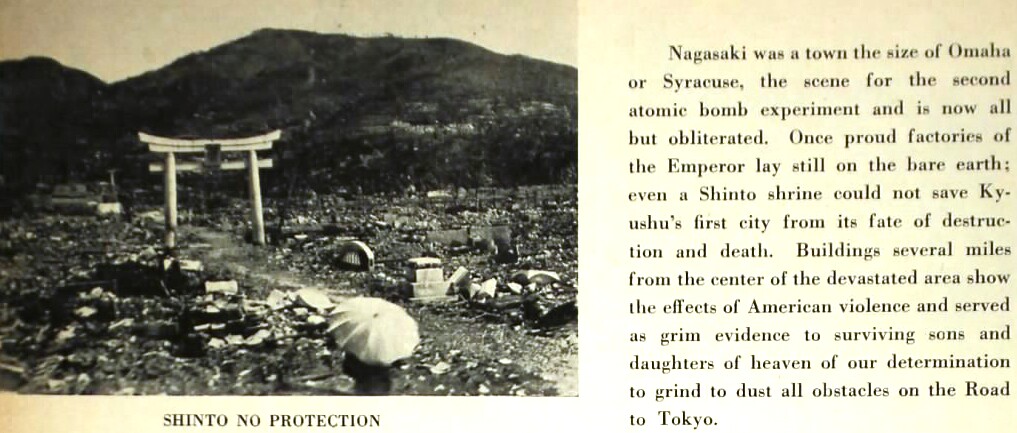

Ground zero BEFORE atomic bombing of Nagasaki, Japan

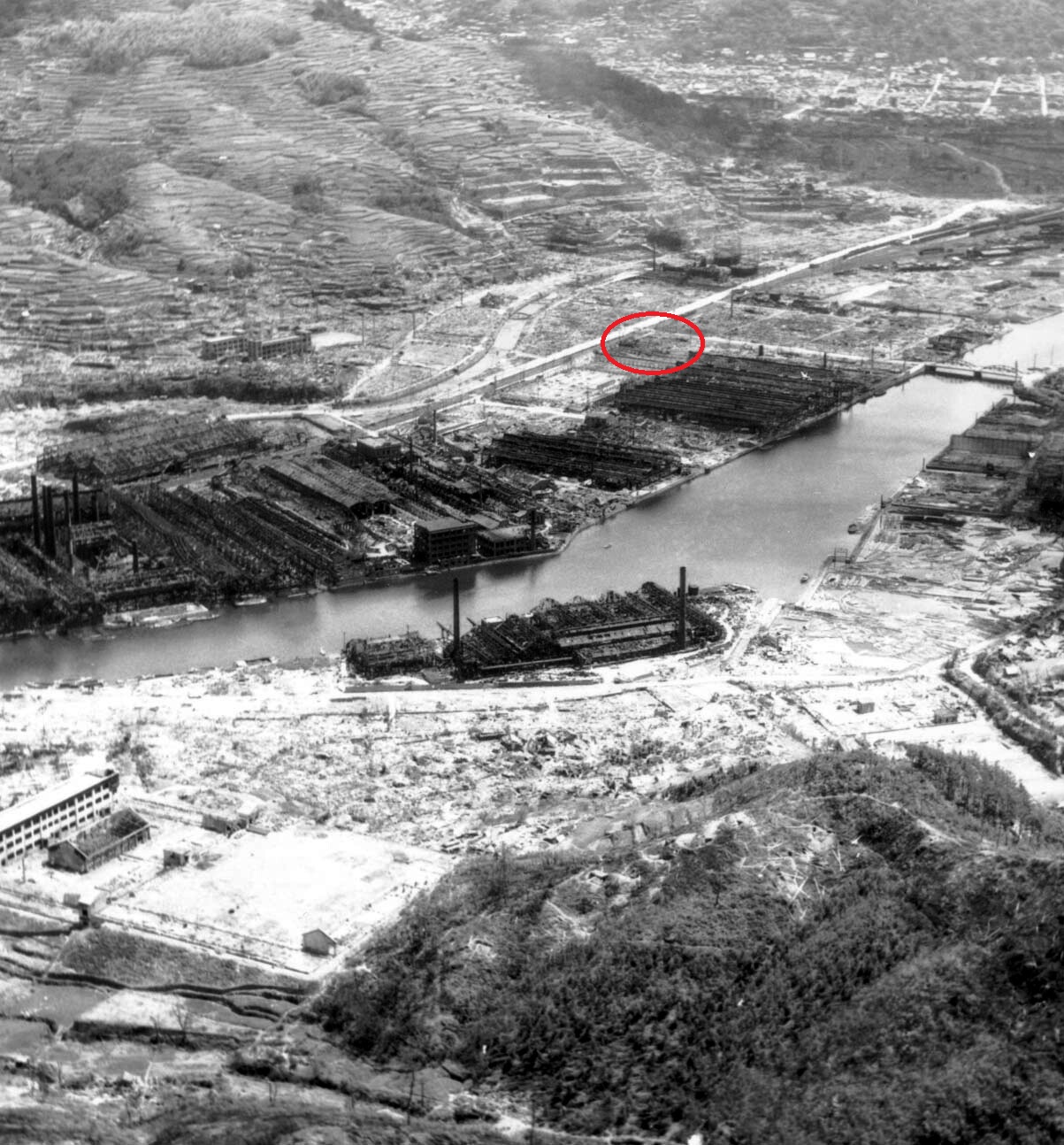

Ground zero AFTER atomic bombing of Nagasaki, Japan

"Ground zero is the spot directly below the explosion of the bomb." (USSBS)

Nagasaki Targets Reports, Oct. 26, 1945

Begins with list of targets on Kyushu island; assorted reports pre- and post-attack, with many aerial images (contains duplicate reports)

Nagasaki Urban Industrial Area Damage Assessment, Sept. 4, 1945

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (1945) - Report by The Manhattan Engineer District, includes damage, injury and casualty data, selection of target, effects, eyewitness account by Prof. Siemes (Hiroshima)

Miscellaneous Targets: Atomic Bombs, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Article 1, Medical Effects, Dec. 15, 1945 - Report by U.S. Naval Technical Mission to Japan; general aspects, effects of radiation on humans, etc. (NOTE: Nuclear physics research in Japan section is missing.)

Photographs of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki 1945 (Manhattan Engineer District)

List of names and addresses of Japanese investigators of A-bombings (USSBS)

Effects of A-bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Captions and narration for a movie on the A-bombings; Nagasaki starts on page 39. Note that the air raid alarm and alert warning continued for several hours prior to the explosion at 11:02AM.

Urakami, Nagasaki

"A panoramic view around ground zero at Nagasaki, Japan. This picture was taken from the platform of the Urakami Railroad Station. The buildings on the right are the remains of the Nagasaki Medical College. 14 October 1945." (USSBS)

The Outline History of Nagasaki City by Kiuchi and Sonoike, Imperial Univ. of Tokyo

"To present a general topographical description of the City of Nagasaki which has become more world famous since it was made the second target of the atomic bomb." Of note: "...the descendants of the Uragami villagers... remained faithful Christians, gave up 30,000 of their lives... for the atonement of crimes by the Japanese militarists."

Nagasaki Trend of People's Morale by Jukichi Okada, Mayor of Nagasaki City (English and Japanese) - Changes in attitudes of the Japanese in their "fighting spirit" during WWII. Of note: "...the workers [including students, women and girls]... did not lose their fighting spirit to the very last, and stuck to their posts." See also Effects of the Atomic Bombs on Morale (USSBS, June 1947).

Nagasaki Special Interviews, Nov. to Dec. 1945

USSBS Morale Division conducted interviews with the following: Jukichi Okada, Mayor of Nagasaki; Eisuke Negishi, Nagasaki College of Industrial Management; Kiyoshi Takese, Nagasaki Medical College; Nagasaki Pref. police; Takejiro Nishioka, president of Nagasaki News; Sadao Urakami, Nagasaki ration officer; Masayoshi Yokoyama, mayor of Tokitsu village; Eiji Nozawa, principal of Tokitsu Youth School; Moto, principal of Nagasaki Methodist Middle School for Girls; Nishioka bio

Japanese Propaganda 1945-08-07 to 09-17 - Summary excerpts of Japanese news relating to A-bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (U.S. Office Of War Information, Overseas Branch, San Francisco; Analysis And Research Bureau, Target Intelligence Division) - Excerpt details showing dates and page numbers from Propaganda3 file

RELATED INTERVIEWS - contain attitudes of Japanese people about bombings and other topics:

Index

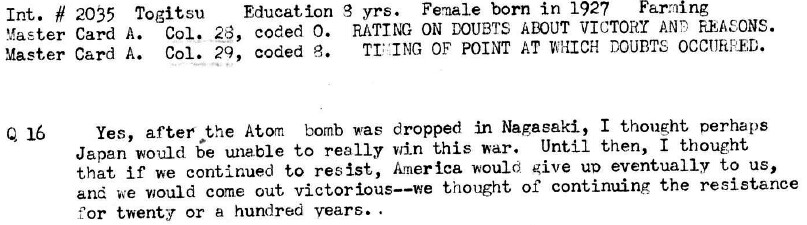

Cards for Interrogations Typical Answers Report No 14h(42)(b)

- wartime morale and attitudes re war, defeat, Emperor, bombing,

Americans, work, propaganda, fighting spirit

Index Cards for Interrogations Colorful Answers Report No 14h(42)(c) - worries, war leaders, defeat, changes, spirituality

Index Cards for Interrogations Unusual Answers Report No 14h(42)(d) - changes, defeat, worries, greatest weakness, war leaders, doubts about victory, certainty of defeat, Emperor, bombings, Americans

Index Cards for Interrogations Colorful Answers Report No 14h(42)(c) - worries, war leaders, defeat, changes, spirituality

Index Cards for Interrogations Unusual Answers Report No 14h(42)(d) - changes, defeat, worries, greatest weakness, war leaders, doubts about victory, certainty of defeat, Emperor, bombings, Americans

Continuing the resistance for a hundred years

Foreign Population Statistics for Nagasaki Prefecture, Nov. 19, 1945

There were some who feared the 3rd city to be bombed would be Tokyo on Aug. 12th:

"On the afternoon of the 12th, San

Francisco broadcasted that the Japanese reply [re surrender] was

very late and intimated that as a result it might be necessary

to bomb Tokyo. (Meanwhile we had heard from a prisoner of war, a

B-29 pilot, that your government planned to use the atomic bomb

on Tokyo on the 12th.)" - Hisatsune Sakomizu, Chief Secretary,

Suzuki Cabinet

Indeed a third

A-bomb was ready for use, with possible

targets having already been listed earlier in April 1945.

Perhaps the next target would have been Yokohama or Tokyo Bay. See

this interesting phone

conversation between War Dept. Gen. Hull and Goves associate

Col. Seeman on Aug. 13, 1945, while waiting for Tokyo's reply:Seeman: "There is one of them that

is ready to be shipped right now. The order was given Thursday

and it should be ready the 19th... the 19th it would be

dropped... Then there will be another one the first part of

September... probably three in October..."

Hull: "...making a total possibility of seven. That is the information I want."

Hull: "...making a total possibility of seven. That is the information I want."

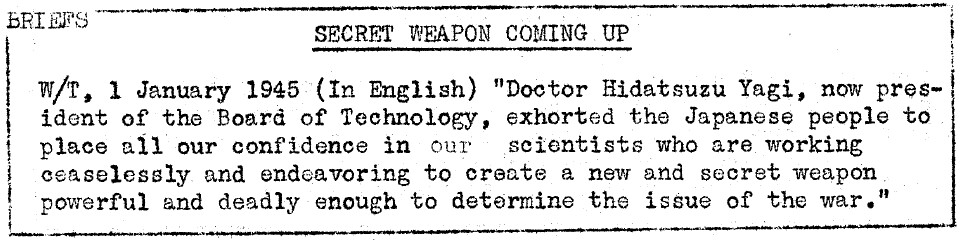

Japanese scientists working to create a new and secret weapon

See this news article re Truman's warning to Japan (Aug. 10, 1945), and this one on page 2. Note that both articles tell of Japan saying it has its own similar A-bomb and will use it in kamikaze planes to decimate US invading forces. To our intel experts, this was not something to be laughed at, for Japan in fact was preparing a huge number of secret weapons (see OUTLINE OF NAVAL ARMAMENT PREPARATIONS FOR WAR). More alarming, it was conducting research into its own A-bomb (see below for more information on the Japanese quest for that super weapon).

The war started with Mitsuo Fuchida leading the attack on Pearl Harbor, and it ended with the Nagasaki A-bomb. Here's what Fuchida had to say to Enola Gay pilot Capt. Tibbets:

"You did the right thing. You know

the Japanese attitude at that time, how fanatic they were,

they'd die for the Emperor. Every man, woman, and child would

have resisted that invasion with sticks and stones if necessary.

Can you imagine what a slaughter it would be to invade Japan? It

would have been terrible. The Japanese people know more about it

than the American public will ever know." - This

Token of Freedom by Helminiak

Use of Atomic Weapons against Japan - CIA Final Months of the War With Japan

Background info on the decision to use atomic bombs against Japan, including statistics on suicide base buildup in southern Japan and other areas

Pres. Truman's views on the use of the atomic bomb

A compilation of messages from Aug. 9, 1945, to Aug. 4, 1954, regarding justification for using the A-bombs against Japan.

"Nobody is more disturbed over the

use of Atomic bombs than I am but I was greatly disturbed over

the unwarranted attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbor and their

murder of our prisoners of war."

|

Excerpts

from

MacArthur's ULTRA: Codebreaking and the War against Japan, 1942-1945 by Edward J. Drea (1992) Page 204: Historians have offered myriad motivations -- from the altruistic to the sinister -- for the controversial decision to wage atomic warfare against Japan. One strongly argued view holds that because Japan was already defeated, the needless and senseless atomic destruction of humanity was done for political ends. Such arguments rest on well-explored political and diplomatic dimensions of strategic decisionmaking concerning the use of the atomic bomb but ignore the military side of that process. ULTRA-derived knowledge of the massive buildup for a gigantic battle on Kyushu did influence American policymakers and strategists. To ignore that factor assumes that the Japanese were defeated and, more important, that they were prepared to surrender before the atomic bomb was dropped. ULTRA did portray a Japan in extremity, but it also showed that its military leaders were blind to defeat and were bending all remaining national energy to smash an invasion of their divine islands. From that perspective, the Imperial Army was as defeated and in as hopeless a situation as Adachi was at the Driniumor, as Yamashita on Luzon, as Suzuki on Leyte, and as Kuzume on Biak. Everywhere in the Pacific, cut-off, outnumbered, and defeated Japanese garrisons had continued fighting to the death. Given that bitter legacy, it was not difficult for American military planners and political decisionmakers to believe that the Japanese stood ready to defend their sacred homeland with equal or greater suicidal ardor than the emperor's soldiers throughout the Pacific war. Page 214: There were also peace overtures. The first hint of such sentiment in Japan itself appeared in an April message deciphered in early July (July 7). Earlier decryptions of Japanese Foreign Ministry telegrams exposed Japanese peace initiatives through Sweden, Switzerland, and the Soviet Union (July 28). As far as Allied military intelligence was concerned, the Japanese civil authorities might be considering peace, but Japan's military leaders, who American decisionmakers believed had total control of the nation, were preparing for war to the knife. ULTRA testified that from mid-July, the number of troops in Kyushu had skyrocketed. Page 224: The next atomic bomb attack against Nagasaki in western Kyushu on August 9, 1945, passed unnoticed in ULTRA channels. Hiroshima monopolized attention, and the war had not ended. Despite the two atomic attacks, American intelligence's study of Japanese naval radio messages for August 15 left the impression that the Japanese were still planning and executing wartime operations with air, surface, and underwater suicide units (August 15). Willoughby was more generous. He argued that there was nothing contradictory in Japanese field commanders urging their troops to greater efforts as Japanese diplomats scurried about seeking peace. Such confusion, Willoughby believed, was a natural outgrowth of the disorder involved in preliminary peace negotiations (August 15/16). Furthermore, broken codes illuminated the emperor's indispensable role in compelling Japan's armed forces to lay down their weapons of war. ULTRA picked up the navy minister's account of the Imperial Council where the final problem of peace or war was submitted to the emperor. "'His and only his' decision was to accept the Potsdam Declaration, 'on the condition that the structure of the nation be left intact'" (August 18). Deciphered message after deciphered message testified to the force of the Imperial Rescript (shosho) of August 14, 1945, as radio messages of compliance poured into Tokyo from units strewn from Java to North China. Southern Army's case exemplified the emperor's unique position in Japanese society. On August 15 Southern Army informed all its subordinate units, which stretched from Rabaul to Burma, that although an imperial statement accepting the Potsdam Declaration had been issued, all Japanese forces would continue to fight. "So long as the Southern Army has no orders, you are not to enter into any negotiations with the enemy, but are to continue to repel him" (August 15/17). Late the next day, after receiving imperial orders, Southern Army instructed all units to obey the emperor's edict. Officers and men were ordered "to observe strict discipline and obey orders to the last, thus proving to the world their fidelity to the Emperor." Other combat formations signaled that "the only road to follow now is united obedience to the Emperor" (August 18/19). This impressive display of authority surely made an indelible impression not only on MacArthur but also on leaders in Washington. One may speculate that it was instrumental in the later American decision to retain the emperor and imperial institution as symbols of the Japanese state despite vociferous calls from other Allies for his indictment as a war criminal. |

Assorted A-bomb-related documents:

Objectives in using A-bomb -

Harrison-Bundy Papers p5262.jpg

Objectives in using A-bomb - Harrison-Bundy Papers p5263.jpg

Where to use first A-bomb Groves Policy Meeting 1943-05-05.jpg

A-bomb to be used against Japan with warning 1944-09-18 - Harrison-Bundy Papers p1940.jpg

A-bomb to be used against Japan with warning FDR-Churchill 1944-09-19 - Harrison-Bundy Papers p2653.jpg

Memo from a Manhattan Project scientist Evan Young 1945-07-14.jpg

Gov Takano Proclamation re Hiroshima 1945-08-07.jpg

Gov Takano Proclamation re Hiroshima 1945-08-07 JAPANESE - Report No 3c-15 USSBS Index Section 2.jpg

Stimson cover letter re A-bomb and surrender article 1946-12-10 - Harrison-Bundy Papers p3068.jpg

Stimson re use of A-bomb - Harrison-Bundy Papers p3081.jpg

Stimson re Japans strength and determination to fight - Harrison-Bundy Papers p3082.jpg

Stimson re Japans strength and determination to fight - Harrison-Bundy Papers p3083.jpg

Stimson re Japans strength and determination to fight - Harrison-Bundy Papers p3084.jpg

Stimson re sparing Kyoto from A-bomb - Harrison-Bundy Papers p3092.jpg

Stimson re sparing Kyoto from A-bomb REVISION - Harrison-Bundy Papers p3111.jpg

No need for A-bombs Intelligence Summary Nos 3189 - 3191 1951-06-05 p212 8341837.jpg

Objectives in using A-bomb - Harrison-Bundy Papers p5263.jpg

Where to use first A-bomb Groves Policy Meeting 1943-05-05.jpg

A-bomb to be used against Japan with warning 1944-09-18 - Harrison-Bundy Papers p1940.jpg

A-bomb to be used against Japan with warning FDR-Churchill 1944-09-19 - Harrison-Bundy Papers p2653.jpg

Memo from a Manhattan Project scientist Evan Young 1945-07-14.jpg

Gov Takano Proclamation re Hiroshima 1945-08-07.jpg

Gov Takano Proclamation re Hiroshima 1945-08-07 JAPANESE - Report No 3c-15 USSBS Index Section 2.jpg

Stimson cover letter re A-bomb and surrender article 1946-12-10 - Harrison-Bundy Papers p3068.jpg

Stimson re use of A-bomb - Harrison-Bundy Papers p3081.jpg

Stimson re Japans strength and determination to fight - Harrison-Bundy Papers p3082.jpg

Stimson re Japans strength and determination to fight - Harrison-Bundy Papers p3083.jpg

Stimson re Japans strength and determination to fight - Harrison-Bundy Papers p3084.jpg

Stimson re sparing Kyoto from A-bomb - Harrison-Bundy Papers p3092.jpg

Stimson re sparing Kyoto from A-bomb REVISION - Harrison-Bundy Papers p3111.jpg

No need for A-bombs Intelligence Summary Nos 3189 - 3191 1951-06-05 p212 8341837.jpg

Franklin Roosevelt and the Atomic Bomb (asst. documents, courtesy of BACM)

Japanese Atomic Bomb Report for Hiroshima (Source: Governor Takano 21 August 1945, Japanese English Report No. 3c(15) USSBS Index Section 2) - "People of Hiroshima Prefecture: although damage is great we must remember that this is war. We must feel absolutely no fear... We must not rest a single day in our war effort... we must bear firmly in mind that the annihilation of the stubborn enemy is our road to revenge. I am confident that with persistence ours will be the eventual victory, but we must subjugate all difficulties and pain and go forward to battle for our Emperor. - Aug. 7, 1945"

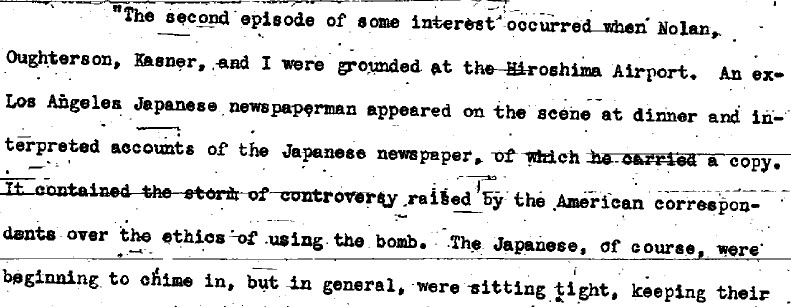

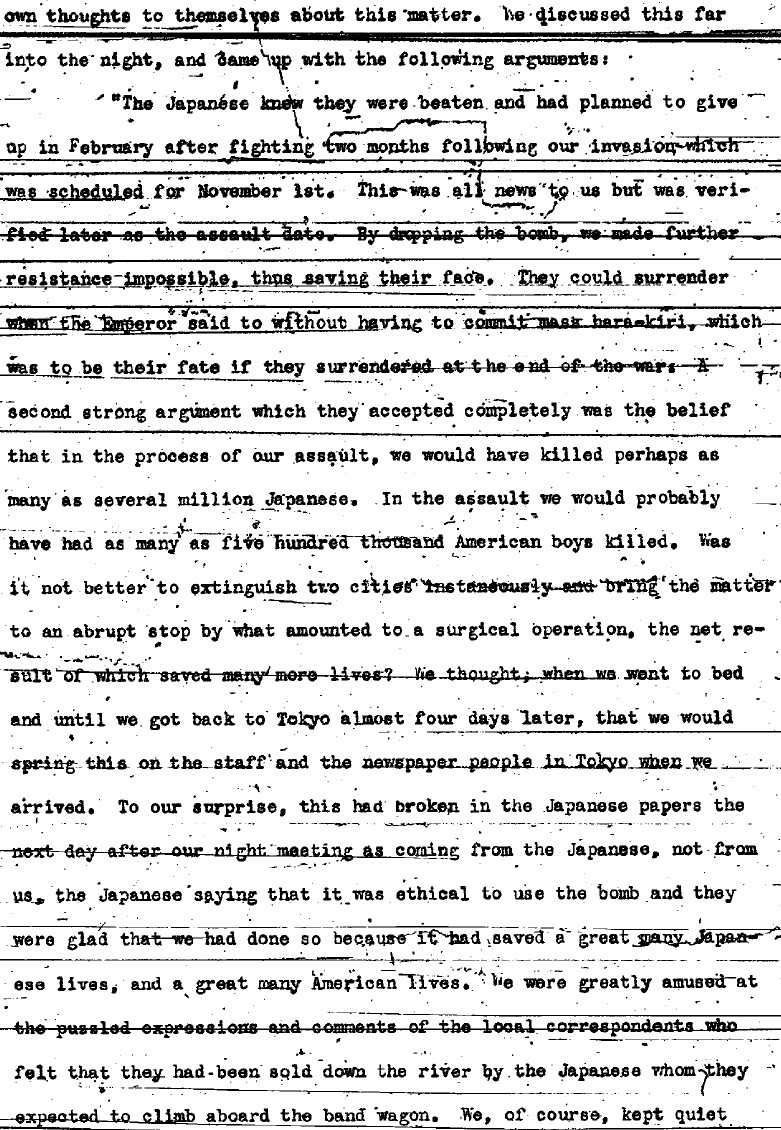

Re the ethics of using the A-bomb, from a report by Brig. Gen. R. C. Wilson:

Source: Manhattan Project History, R1-B1-V4-C6, Investigation of the After Effects of the Bombing in Japan, Ground Accounts

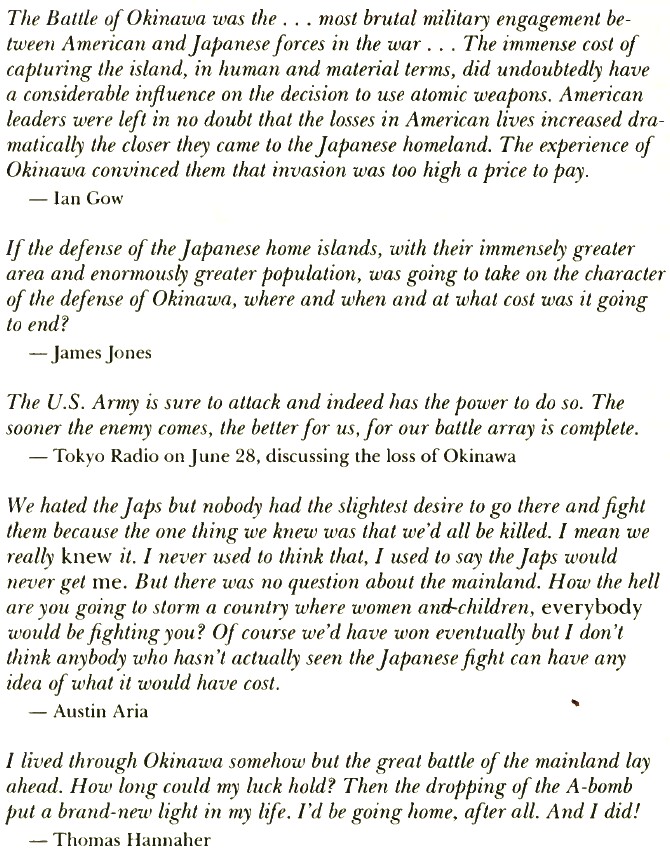

Was the A-bomb necessary or not? Reading the final chapter, "The Atomic Bombs," from the book, Tennozan: The Battle of Okinawa and the Atomic Bomb by George Feifer (1992), will help clarify the answer to that question.

For other related documents, see Special Files- Atomic.

For more insight into Japan's atomic research, read:

The

Japanese Wartime Atomic Energy and Weapons Research Program –

Seishin (Chongjin), Northern Korea. 1938 - 1984 by Dwight

Rider

Dwight Rider on the reason why Japan surrendered: "The Japanese government was definitely concerned about the growth of a communist movement inside Japan at that time and the future of the Japanese Emperor system, and that is why they surrendered. Again, it was because of the bomb, not the Soviet invasion, and the potentially growing threat of communism inside Japan in wake of a total collapse, that prompted them to do that. Finally, in the Emperor's own statement, he credits the bomb as being a terrible new weapon which could lead to the destruction of humanity as his reason to surrender, not the USSR. The USSR was only part of the deteriorating events that contributed."

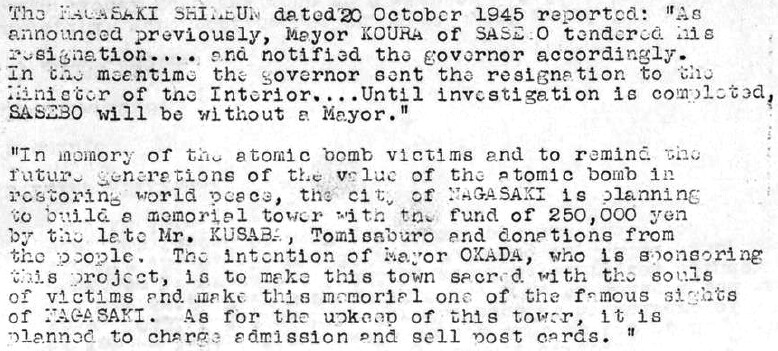

To remind future generations of the value of the atomic bomb in restoring world peace

|

Assorted excerpts

from Japan's Imperial Conspiracy

by David Bergamini (1971, Vol 1) p5 In 1937, when the crime of Nanking did not yet burden the Japanese conscience, Japan had been wresting territory from China for over forty years: the island of Taiwan and the peninsula of Korea in 1896; a New-England-sized piece of Manchuria in 1931; the remaining Texas-sized piece of Manchuria in 1932; the Kansas-sized province of Jehol in 1933; and Montana-sized Inner Mongolia in 1935. Then in the summer of 1937 Japan went on to launch a full-scale invasion of all that was left of China, the populous heartland of some 500 million souls extending from the Great Wall in the north to the borders of Indochina, Siam, Burma, and India to the south. First, in July, Japanese armies captured Peking, the old imperial capital in North China. Then, in August, Japanese forces began to fight at the mouth of the Yangtze River for the huge port of Shanghai which laid claim, with New York, London, and Tokyo, to being the largest city in the world. Shanghai was the doorway to Central China. Once unlocked, it would open an easy passage to Nanking, the Chinese capital, which lay 170 miles inland up the Yangtze River. ==================== p81 If the Throne was to keep its power in secret and Japan was to lie low for one hundred years, the people of the country would have to be carefully prepared. The fighting men had staked their honor on victory or suicide, and hundreds of thousands had died in the Emperor's name. If peace were declared prematurely, patriots would say that Hirohito lacked courage to fight the war through. Widows and orphans would blame him for letting their loved ones die in vain. To save the nation's face, then, the war must be continued until everyone had suffered from it and was eager to see it finished. At that point the people could be made to feel that they had fought poorly and let the Emperor down. At that point, if Hirohito declared peace, the people would feel obligated to him. p84 Throughout the planning of peace, Lord Privy Seal Kido encouraged Hirohito to maintain a bold public front of fight-to-the-finish. Only thus could the honor of the samurai be satisfied. Only thus could the people be kept at their jobs. Only thus could the enemy be made to appreciate the expense involved in reducing Japan's island strongholds. Only thus, finally, could the Americans be persuaded that the real power in Japan lay not with calculating civilians of the highest caste but with soldier fanatics from one of the lower castes. p85 Later, in the autumn of 1944, Hirohito sanctioned the manufacture of "special attack weapons," kamikaze planes and torpedoes designed specifically for suicide missions. He put his seal on plans for fire lanes across the major cities, swathes of houses cut down to minimize the effectiveness of incendiary bombing. He supported, in his edicts and rescripts, a campaign of domestic propaganda calculated to persuade the people that the U.S. government meant to rape and destroy Japan thoroughly in the event of defeat. A year passed in which Japan lost battle after desperate battle. When Saipan and the Marianas fell in June of 1944, Hirohito was persuaded that perhaps a new prime minister would tempt the U.S. government into making a peace offer. Hirohito therefore withdrew his support from Prime Minister Tojo, who was supposed in the United States to be the arch-militarist, and smoothly replaced him with a less notorious member of the imperial cabal, reserve General Koiso Kuni-aki. Although he had masterminded much of the plotting for the conquest of Manchuria in 1931, Koiso was little known outside Japan. Wizened and narrow-eyed, the new prime minister looked more like a Chinese opium den proprietor than a Japanese head of state. He was known in Japan as a man of guile, a specialist in counter-espionage rather than combat. His appointment signified that Japan was no longer trying to win by conventional force of arms but only to salvage what she could by intrigue. It was under Prime Minister Koiso's guidance that Japan now resorted to human bombs, human torpedoes, and banzai charges. Though they made U.S. victories costly, the kamikaze tactics could do no more than slow the leapfrog approach of American task forces. p89 From the last week of January until early in April, 1945, Hirohito gave private audiences, one by one, to each of the admirals and generals in the top echelons of the military bureaucracy, to each of Japan's former prime ministers, and to a number of lawyers, professors, cartel owners, and mouthpieces for slum gang lords. By mid-March there was hardly a man of influence who had not pledged his silent unselfish co-operation in the plan for national survival. As each of them emerged from the Imperial Library or from the audience chamber in the bunker below, he had further conversation with Lord Privy Seal Kido and learned what specific service he might render. While the political muster continued, so did the military bluster and bluff. Nine thousand obsolescent planes were hidden in forest airstrips. Suicide pilots were put in training to man them. Gangs of peasant volunteers drove stakes and dug entrenchments along Japan's sacred beaches. Exhibits of hoes, rakes, axes, bamboo spears, and other rustic secret weapons were mounted in such public places as the lobby of the prime iminister's residence. The last concrete was poured at the headquarters of final resort under the Japanese Alps. The Americans were promised a "final decisive battle" if they ventured to land, as anticipated, in the coming autumn. p98 On June 18, President Truman approved plans for Operation Olympic which would have sent a million Americans into the beachheads of southern Japan in the coming November. To support the invasion, Chief of Staff Marshall in Washington was expecting to need—for "tactical use"—no less than nine of the new untried atomic bombs. p101 Unknown to Stalin, unknown to Hirohito, the telegraphic correspondence between Togo and Sato was being intercepted by U.S. Intelligence; it was decoded, translated, and submitted to Secretary of State Byrnes. It revealed clearly that Japan was desperate to surrender. It did not reveal the minimal face-saving terms which Lord Privy Seal Kido and members of the General Staff had agreed to accept months earlier. It did not show any wilhngness on the part of the Japanese to settle for the one condition which had already been granted through O.S.S. Chief Dulles. U.S. Intelligence analysts tended to see Japan as a brutal police state under the control of a few tough fanatic generals like Tojo. The analysts did not know that Tojo was only an obedient servant of the Throne. They did not know that the Emperor's civilian advisors were at least as influential as his military aides. The power of the Japanese Army was judged by its arrogant totalitarian behavior in conquered countries overseas. It was not fully appreciated that most Japanese soldiers were of humble birth and that this made them subservient to aristocratic civilians at home. p103 Churchill was to add later: "The decision whether or not to use the atomic bomb to compel the surrender of Japan was never even an issue." In Truman's mind, however, it was a source of uneasiness. On July 18, the day the President received details of what the bomb could do, he consulted with his military advisors and with anyone else whose opinion might be valuable. General Eisenhower, who was visiting in Potsdam that day, remembered in later years that he had been sounded out by the President and had "expressed the hope that we would never have to use such a thing... take the lead in introducing into war something as horrible and destructive." Stimson, however, maintained that the bomb might be the excuse the Japanese were waiting for, and he urged that it be used "in the manner best calculated to persuade the Emperor to submit to our demand for what is essentially unconditional surrender." Churchill and other statesmen sided with Stimson. And so on July 24, while still at Potsdam, the President issued the operational order to General Carl Spaatz that the first "special bomb" should be dropped by the "509 Composite Group as soon as weather will permit" after about August 3. p106 While the generals waited, Emperor Hirohito and his advisor Lord Privy Seal Kido already knew the answers. When they met in the Imperial Library that afternoon, both had seen Naval Intelligence analyses and reports from physicists at Tokyo Imperial University. The claims being broadcast from the United States were almost certainly honest. It had been an atomic bomb. Emperor Hirohito had received remarkably accurate statistics as to the casualties: "130,000 killed and wounded." Unlike most of his countrymen Hirohito understood what genshi bakudan, atomic bomb, signified. Until a few months previously, he had patronized Japan's own atomic research effort. It had come to a disastrous end when a physicist, some technicians, and two buildings full of apparatus had been mysteriously blown up. Under pressure to save Japan from defeat, the work had been pushed ahead too fast and safety precautions had been neglected. (The physicist was named Odan, thirty-eight years old; the explosion was probably caused by careless handling of liquid gases.) p107 On Thursday morning, August 9, when the second bomb was scoring its merciful two-mile miss, the Big Six of the Japanese Government had just gathered in the prime minister’s air raid shelter outside the palace to debate the Emperor’s wish to accept unconditional surrender. They had been summoned the previous evening, but some of the military members of the group had made themselves unreachable. During the night, however, pressure for instant action had mounted when the secret police circulated news of a "confession" made by a B-29 pilot shot down the day before in Osaka. Already bruised and bloodied by his interrogators, Lieutenant Marcus McDilda had been threatened with death unless he revealed what he knew about the atomic bomb. Knowing nothing, he decided to tell all. "As you know," he began in his Florida drawl, "when atoms are split, there are a lot of plusses and minuses released. Well, we've take these and put them in a huge container and separated then from each other with a lead shield. When the box is dropped out of a plane, we melt the lead shield and the plusses and minuses come together. When that happens, it causes a tremendous bolt of lightning and all the atmosphere over city is pushed back. Then when the atmosphere rolls in again it brings about a tremendous thunderclap, which knocks down everything beneath it. "I believe," added McDilda under prodding, "that the next two targets are to be Kyoto and Tokyo. Tokyo is supposed to be bombed in the next few days." As the war minister and the two chiefs of staff sat down with the other members of the Big Six to discuss Hirohito's request in the sweltering air raid shelter, they exchanged information about McDilda's confession and felt oppressed by the thought that Tokyo and the Emperor, or Kyoto and the tombs of past Emperors, might soon be turned to ash. the same time, they also feared an end to the war. They still had at their disposal in the home islands 2.5 million combat-equipped troops and 9,000 kamikaze planes. These men had been told for years that death was preferable to surrender. For months they had been promised "a final decisive battle" on the shores of Japan, a battle so costly to the enemy thai it might be possible afterwards to negotiate a conditional surrender and win an honorable peace. To surrender these men without a fight evoked visions of unbearable future shame—of the veteran in rags who would spit on any general he passed on the street and feel justified in doing so. p114 In the real bunker, that evening of August 9, 1945, the cynical, impressionable Secretary Sakomizu saw the ghostly proceedings open with a ceremonial recitation of all the anguished arguments of the preceding days. Hirohito sat listening mute and immobile, ramrod stiff at the altar before the golden screen. Foreign Minister Togo and Navy Minister Yonai reviewed the inescapable reasons for accepting unconditional surrender. War Minister Anami and Army Chief of Staff Umezu begged—for the honor of the living and the dead—to fight a final battle. p128 The next afternoon, however, Tojo heard further rumors and at 6:30 p.m. on Tuesday, August 14, he was again in Tokyo talking to War Minister Anami as he took a bath during a brief Cabinet recess. Anami, whom Tojo had known for twenty years as a junior member of Hirohito's cabal of young officers, was strangely preoccupied and reticent. But Tojo understood enough from his belly talk to stress vociferously that the way to deal with the American conquerors was not to try to deceive them but to stand up to them honestly. "After the surrender," he said, "we will all of course be tried by a military court as war criminals. That goes without saying. What we must do when the time comes is all stand together. We must be forthright in stating our belief that the Greater East Asia War was necessary. What we fought was a defensive war." |