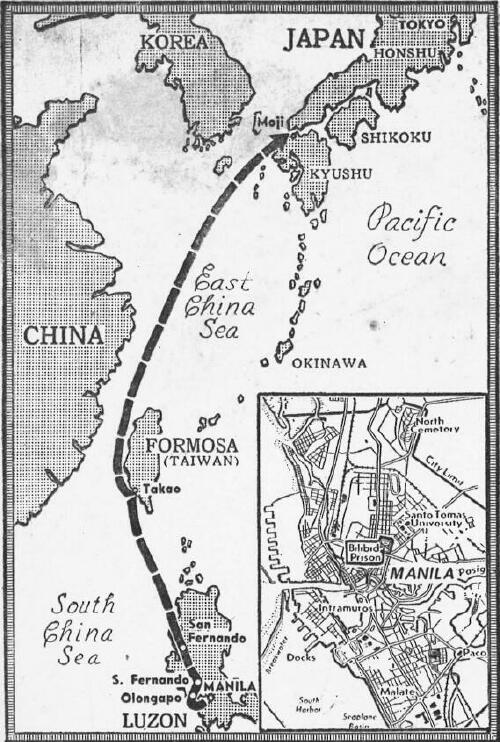

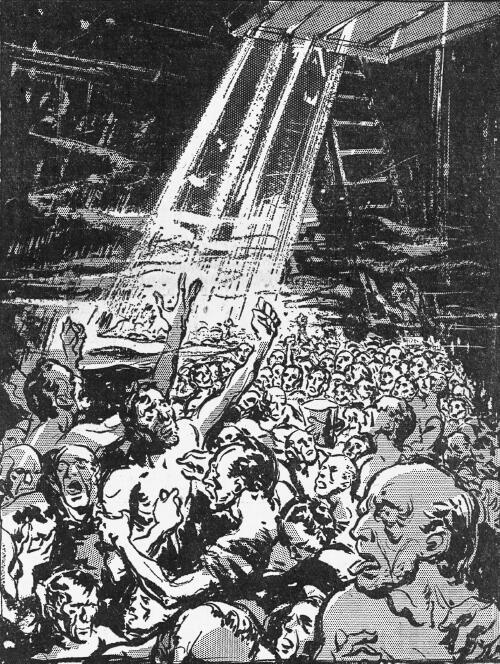

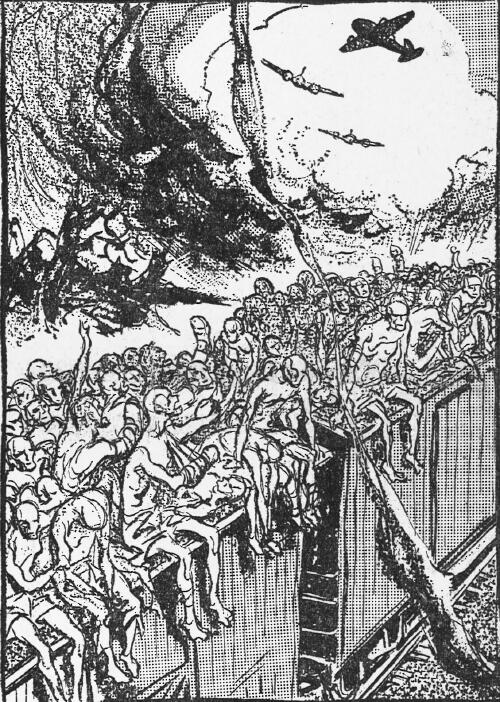

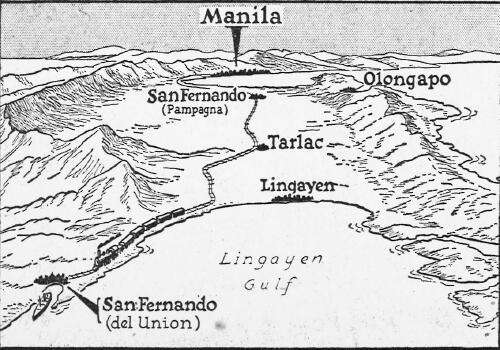

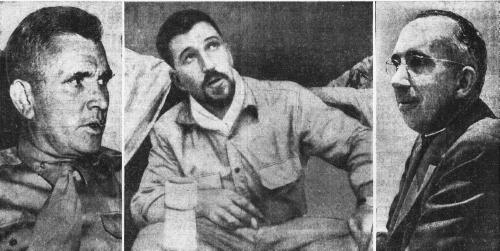

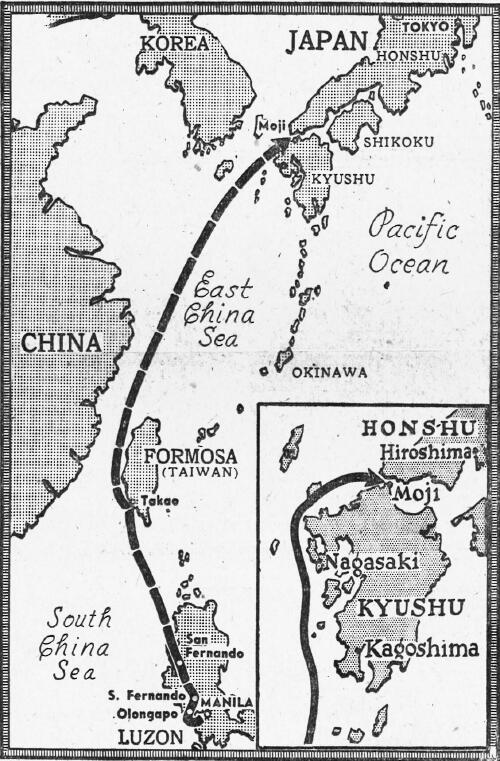

CHICAGO DAILY NEWS. Thu., Nov. 8, 1945. CRUISE OF DEATH1,600 Yanks In Living HellOnly 300 Survive Horrors Of 2d 'Black Hole of Calcutta'THIS is the story of the cruise of death. It is the story of 49 days of savagery and tragedy unequaled in the war in the Pacific, of a Jap-made hell from which approximately 300 Americans from more than 1,600 emerged alive.This historical document was prepared from the stories of the survivors by George Weller of the Daily News Foreign Service. They were interviewed in prison camps and rest camps in Japan, on hospital ships and at U.S. bases in the Pacific. It is the story of a twisting, torturous journey on prison ships from Manila to southern Japan, during which men died from Jap bullets, American bombs, suffocation, disease, starvation and murder. Some went insane. An official record cannot be prepared for many weeks. Absolutely reliable lists of living and dead are unobtainable in the Pacific at present. In spelling names some phonetic methods had to be used because of the uncertainty of the survivors. Otherwise its accuracy is undoubted. The story begins in Manila. Dec. 13, 1944. How 1,200 Yanks Died on Jap ShipSurvivors of Horror Journey To Prison Tell Pitiful StoryBY GEORGE WELLER. Daily News Foreign Service. Thin from nearly three years' confinement, guarded by Japs with bayonets, a column of American prisoners numbering somewhere above 1,600 men shuffled in ranks of four through Manila's dusty streets. They were on their way from Bilibid Prison to what in prewar days had been known as "the Million Dollar Pier." The sun was hot and many of them were ill. The ragged street boys made them furtive V-for-Victory signs. In the lace-curtained parlors of the poor Philippine homes the cheap radios were turned on full blast as they approached, then tuned down after they left -- an indirect salute of the underground.  Veterans of Bloody Corregidor Nearly all the prisoners were veterans of the defense of Bataan, Corregidor and Mindanao. About half were officers, representing about 90 per cent of the field, staff and medical officers who had sustained the defense of the Philippines for six months without help from the United States. They ranked from Navy commanders and lieutenant colonels of the Army and Marine Corps down through lieutenants and ensigns. Some were civilians who had been commissioned hastily after Japan struck south. Others were civilians who had helped in the defense of Bataan and Corregidor without ever having formally entered the armed forces. There also were 37 Britons. The 1,600 prisoners (the exact number is given by various survivors as 1,615, 1,619 and 1,635) had heard that they were being sent to Japan. If true, it meant that their long-sustained hope of being rescued by Gen. MacArthur's forces was ended. They Didn't Know What They Faced The prisoners expected that their journey by sea to Japan might take a week or 10 days. Had they realized what lay ahead of them -- that some would die of suffocation before even the next dawn -- many undoubtedly would have chosen immediate death on the bayonets of their Jap guards. The trip lasted seven weeks and at its end slightly more than 400 were left alive, of whom 100 died soon after landing. Many of the prisoners were survivors of the Death March from Bataan to Camp O'Donnell, where the willful denial of water and food by the Japs cost the lives of hundreds of Americans. 'They could not know that this journey would be no less cruel and far more extended than the Death March, that it would be a trip which for deliberate butchery and needless sacrifice would take its place with the Black Hole of Calcutta. 1,880 Crammed Into Manila Prison About 1,880 prisoners were crammed into Bilibid Military Prison in downtown Manila when the Japs decided to move them to Japan. They were thin and weak. Their sustaining dish in Bilibid was lugau, a watered rice made into a. thin, gluey substance. So unnourishing is lugau that many barely had strength to move about the prison. Against this liability of weakness the prisoners had an asset: a dedicated group of doctors, both Army and Navy, poor in medicine but rich in spirit. The Japs had made plans for evacuating the Americans sooner, but Manila was under almost constant Yank air bombardment. For some reason, however, the air attacks stopped suddenly on Nov. 28, giving the Japs their chance to sneak their freighters into Manila. As the prisoners dragged themselves to the pier, they feared that MacArthur would come too late. The column reached the Million Dollar Pier about 2 p.m. It was crowded with Jap civilians by hundreds, all well dressed, with wives, babies, luggage and often large casks of sugar. And there was the Oryoku Maru, a passenger and freight ship of about 9,500 tons, built in Nagasaki in 1939. Japs Put Officers in the Hold On hand to supervise the prisoners were several Japs whom the prisoners knew. There was Gen. Koa, who was in charge of all prisoners in the Philippines, and Lt. N. Nogi, director of the Bilibid hospital, a former Seattle physician who in general had been kind to Americans. The Japs elected to fill the aft hold first, and to put aboard the 500 highest ranking officers before the others. It was this circumstance which was to make the death toll the heaviest the first night among the top officers, men who had commanded regiments and battalions in the hopeless struggle for Bataan and Corregidor. The aft hold's hatch was cut off from free circulation of air by bulkheads fore and aft. A long slanting wooden staircase dipped 35 feet through the hatch, down which the prisoners crept. When the first officers reached the bottom of the ladder they were met by a Sgt. Dau, well known at Davao. His men used brooms to beat the American officers back as far as possible into the dim bays of the hold. Japs Keep Driving More Men Down "We had to scamper back in there," one officer describes it. "There was a platform about 5 feet high built over the hatch above, and so the little light that came down in mid-afternoon was deflected. "Long before the hold was filled the air was foul and breathing was difficult. "But the Japs kept driving more men down the ladder from the deck, and Dau and his men kept pushing the firstcomers farther back into the airless dark." The first officers who had descended were sitting in bays, a double tier system of wooden stalls something like a Pullman car. The lower bays were 3 feet high. A man could neither stand nor extend his legs while sitting in them. Each bay was about 9 feet from passageway to rear wall. The Japs insisted that the Americans could sit in rows four deep, each man's back against his neighbor's knee, in this 9-foot depth. A Black Pit of Living Men The elder officers who were forced back in the rear almost immediately began to faint. Instead of making more space in the center under the fading light of the hatch, the Japs insisted that the men in the center should not even sit, but should be left standing, packed together vertically. When the Japs on deck looked down through the hatch they saw a pit of living men, staring upward, their chests and shoulders heaving as they struggled for air and wriggled for better space. "The first fights," says one officer, "began when men began to pass out. "We knew then that only the front men in each bay would be able to get enough air." (Tomorrow: The Horrors of the Damned.) CHICAGO DAILY NEWS. Fri., Nov. 9, 1945. DEATH CRUISE -- CHAPTER 2Yanks Go Mad On Agony ShipDead Crammed In with Living In Hell-Hold of Jap VesselThis is the second in a series of articles on the Cruise of Death -- 49 days of filth, starvation and madness aboard Jap hell ships transporting 1,600 American prisoners from the Philippines to Japan. Three hundred men were alive when it was all over.The survivors' stories were gathered by George Weller of the Chicago Daily News Foreign Service in prison and rest camps, hospital ships and U.S. bases. BY GEORGE WELLER. Daily News Foreign Service. On Dec. 13, 1944, the Japs began herding some 1,600 Americans, already weak and ill from nearly three years in Philippine prison camps, into the holds of the hell ship Oryoku Maru in Manila. About 800 men, including most of the higher-ranking officers, had been jammed into the dark, airless, foul-smelling after hold. There men already were face to face with death and the battle for survival. Meanwhile, the Japs were herding about 600 others forward into the bow hold. The air here, too, was foul. Finally, the last party to board, approximately 250 enlisted men and civilians, got the only fully ventilated hold of the Oryoku Maru, the second hold forward. About 5 o'clock the Oryoku Maru headed down the bay. The prisoners were in charge of Lt. Toshino, an officer of somewhat Western and Prussian aspect, with short clipped hair, spectacles and a severe manner. THOUGH TOSHINO was nominally in command, the real control fell, as it often did in Philippine prisons, into the hands of the interpreter, in this case a Mr. Wada. No survivors of that trip ever will forget him. MR. WADA was a hunchback. He hated the straight-backed world with a cripple's hatred, and all his hatred had turned itself on the Americans. For some reason he always was called "Mr." Wada. The Oryoku Maru, as it moved down the harbor, became part of a convoy of five merchant ships, protected by a cruiser and several destroyers and lighter craft. They moved without lights, their holds vomiting forth the hoarse shouts of the Americans. Discipline had begun to slip in the struggling pits of the No. 3 and No. 1 holds. As air grew scarcer, the pleas for air grew louder and more raucous. Before long the Japs threatened to board down the hatches and cut off all air.  Japs Lower Food Buckets As the cries persisted, the Japs lowered down into the complete darkness of the pit a series of wooden buckets filled with fried rice, cabbage and fried seaweed. In the stifling darkness, filled with moans and wild shouts, the buckets were handed around. The officers who had mess kits, scooped in the buckets. The others simply grabbed blindly in the darkness, palming what they could. Those in the rear ranks got little. Fear already was working its way on the bowels and kidneys of the men. Asked for slop buckets, the Japs sent them down. But these buckets circulated in the utter darkness far less rapidly than the similar food buckets. A man could not tell what was being passed to him, food or excrement. In their increasingly crazed condition, men would tell their neighbors that the one bucket was the other, and consider it uproarious if a hand was dipped in the wrong container. MR. WADA was annoyed by the clamor. "You are disturbing the Japanese women and children," he called down from the top of the hatch to Cmdr. Frank Bridget, who was shouting himself, hoarse trying to keep order among the suffocating men. "Stop your noise or the hatches will be closed." Hatches Closed Over Prisoners The noise of the crazed men could not be stopped and the hatches were closed. That was about 10 p.m. Then some of the men crept up the ladder and parted the planks slightly, so that a little air could get through. Mr. Wada came again to the edge of the pit: "Unless you are quiet I shall give the guards the order to fire down into the hold." A kind of relative quiet came -- the quiet of exhaustion and death. The floor was covered with excrement. Almost all the officers had stripped, so that their pores would have a chance to breathe what the lungs could not. OCCASIONALLY an American would awaken from a stupor, out of his mind. One began calling, around midnight, "Lt. Toshino, Lt. Toshino!" The others, fearful that the hatch would be closed again, shouted, "Knife him, knife him!" Someone said, "Denny, you get him!" There was a movement, a struggle and a scream in the darkness. Then somebody else called: "Get Denny, he did it; get him!" And there was another struggle. Then there was foreboding quiet, all who heard wondering what had happened. Men who owned jackknives unclasped the big blade, prepared to fight if they were attacked. Death Walks In the Ship The Oryoku Maru crept through the mouth of Manila Bay and turned northward in the darkness, hugging closely the Luzon shore so that the remaining vessels in the convoy could protect her. Meanwhile, death strode through the fetid, slippery holds, striking impartially. Maj. James Bradley of Shanghai's famous 4th Marines died. Lt. Col. John H. Bennett of the 31st Infantry suffocated and so did Lt. Col. Jasper Brady of the same outfit. Lt. Col. Norman B. Simmonds, a former college middleweight boxing champion, went down and did not arise. Maj. Houston B. Houser, an outstanding figure who had organized M.P.'s of a sort to keep order in the darkness, fell from exhaustion and later took the short way home. He had been Lt. Gen. Wainwright's adjutant during part of the battle for Bataan. BUT IN the darkness few knew that these men had died. It is even possible that some actually did not die until the next evening. "Once you passed out, you were gone," an officer said, "but only those near you could tell that you were dead. "The temperature down there must have been 130 degrees at least, and it took a long time for a body to grow cold." Men Go Mad In the Darkness "The worst thing," according to a major of the 26th Cavalry, "was the men who had gone mad but would not sit still. "One kept pestering me, pushing a mess kit against my sweaty chest and saying, 'Have some of this chow? It's good.' "I smelled what it was. It was not chow. 'All right,' he said, 'if you don't want it I'm going to eat it.' "And a little while later I heard him eating it, right beside me." THERE WAS a tendency on the part of men near the border of madness to get up and wander around, as though to get assurance where they were. "You would meet one of these men," a survivor said. "He would seem to talk perfectly normal. "But he would keep putting out his hands, placing them on your shoulders in the darkness, running them up and down your arms in the darkness, as though trying to make sure that you and he were alive, and that you both were real." AFTER THE hatches were closed the Japs refused to allow any more benjos, or slop buckets, to be handed up the ladder. Overfull as they were, the buckets still circulated. The floors became slippery with filth. By the Dawn's Early Light As dawn's first light crept through the parted planks of the hatches, the men looked about them. Some were in a stupor, a few were dead, a few were mad. The first step was to get the insane under control. In the aft hold, which was the worst affected, there were two decks and a bottom hatch, leading into the bilge. The most violent of those who were mad were lowered into this sub-hold. IT WAS HOT. The labored working of hundreds of lungs had expelled moisture which clung to the sides of the bulkheads in great drops. Men tried to scrape off this moisture and drink it. Naked, they sat like galley slaves between each other's legs. They were in the first stages of weakening through dehydration, aggravated by the loss of body salts, the sparks of energy. (Monday: Bodies clutter holds as death strikes more often.) CHICAGO DAILY NEWS. Mon., Nov. 12, 1945. Death Cruise: Crazed Men Sip BloodCHAPTER 3Hell Ship Cluttered By Yanks' BodiesSome Slain by Their Fellows; American Planes Attack VesselBY GEORGE WELLER. Daily News Foreign Service. Jammed into the airless, filthy pits of hell that were the three holds of the Jap prison ship Oryoku Maru, approximately 1,600 American prisoners fought for life. The heroes of Bataan, Corregidor and the march of death to Camp O'Donnell were face to face with death again. Some already had failed. They had suffocated, been slain by their fellows or had simply died of weakness from almost three years in prison camps. Some were insane, all were naked or nearly so, and hungry, thirsty, sick. It was December, 1944, and they were on their way from Manila to Japan. Already they had spent one night in the black, horror-filled holds, a night so thirsty that some men drank blood. Dawn came slowly and at first almost no light filtered back into the rear bays, or shelves, where most of the dead lay. Again the grey-haired, indefatigable Cmdr. Frank Bridget took charge. He had a fighting build, under medium size, with a thin face and bow legs. TO THE FEW who were not naked -- some had kept on their clothes even in the dripping heat as protection against being pawed by the wandering insane men -- he said: "Take off all the clothes you can. Don't move around. "You use up extra oxygen that way and you sweat more. Use your shorts to fan each other." He showed them how the little air that came down the hatch could be fanned with easy motions back into the rear bays. Some of the officers in the rear bays, lying in a stupor between suffocation and life, came slowly alive. Others did not stir. The Japs lowered a little rice. There was no water. Five Officers Sit Up -- Dead In a 10-foot circle around Warrant Officer Clifford E. Sweet were five officers, sitting doubled up and naked. They were dead. The men wondered particularly what had happened to one big man who had kept walking around all night, stepping indifferently on bodies and followed by curses wherever he went. This vagabond kept getting into fights wherever he roamed in the fetid dark. In the faint light they could see the big man, crumpled on the filthy deck, dead. BRIDGET was a fountain of hope. He climbed to the top of the hatch ladder into the very muzzle of the Formosan guard. He persuaded the Japs to allow three or four of the unconscious older officers to be laid out on the deck. But none of the dead was allowed to be removed. In the growing light, with the unbalanced men out of the way and the dead no longer taking their share of air, it was possible for the officers to take stock. "The whole space in the aft hold," according to Maj. John Fowler of Boston and Los Angeles, a 26th Cavalryman taken at Bataan, "looked to me about 100 feet long by about 40 feet wide. "There were about 13 bays or little compartments on each side, and two across. Each bay was double, above and below, and the average was about 8 feet by 11½ feet." Yank Planes Dive on Vessel The Oryoku Maru coasted slowly along the edge of Luzon. In the morning, summoned perhaps by the submarines which had attacked the convoy during the night, American planes were overhead. Bridget, completely cool, sat at the top of the ladder. He called the plays: "They're diving! Duck, everybody!" The Jap gun crews opened fire and guns chattered wildly. Bombs smashed into the water. The bulkheads shook. The naked men lay flat on the filth-smeared planks, trembling.  OUT OF BOMBS but not out of gas or bullets, the planes returned and began to strafe the ships, causing much damage. Though the American fliers brought terror to the prisoners, they also brought two gifts -- light and air. In the shock and disorder, the covering hatch planks had become disarrayed. At length, Lt. Toshino, in charge of the prisoners, and Mr. Wada, the hunchbacked interpreter, gave permission for some of the dead to be brought up on deck. THERE WAS an improvement in morale and partial recovery of discipline in the holds. The situation was not altogether hopeless. If it grew better, they would live. If it grew worse, and the attacks continued, the Japs could not send them to Japan, and they would be rescued by Gen. MacArthur after all. Prisoners Seek Blood to Drink Bridget and Cmdr. Warner Portz, who as senior officer was nominally in charge of the whole party, took advantage of the slight lift in hope to order a roll call. Some sobering discoveries were made. The madness, induced mainly by lack of air and partly by lack of water, had caused men to pair off by twos in the night and go marauding. If they could not have water, they would have blood to drink, and if not blood, then urine. There were slashed wrists. And "Cal" Coolidge, a large, fat former Navy petty officer who had been proprietor of the Luzon bar in Manila, was found choked to death. There had been murder then; the prisoners accepted that, too, with what distaste they could muster, but it seemed a natural part of the whole. A FOOD DETAIL that was allowed to go forward to the galley reported that a big ship was burning in the convoy, and that the ships were turning back toward Subic Bay. Among the 2,000 Jap civilians on board there was terror and confusion. From the forward hold, where Lt. Col. Curtis Beecher of Chicago was in charge, Army physicians, Lt. Col. William D. North and Lt. Col. Jack W. Schwartz, along with several doctors and medical corpsmen, were summoned to take care of the Jap wounded. Blood seeped down through the hatch planks and gave the naked, panting men a spotted appearance. Yanks Outwit Jap Guards In the middle hold, where approximately 250 men were under Cmdr. Maurice Joses, Santa Monica, there was enough air to maintain discipline and plenty of room. This group even had resourcefulness enough to keep back the wooden buckets that the Japs sent down with food. By retaining one each time they were able to accumulate enough benjos, or toilet buckets, for themselves. By this time in the other holds men were using their mess kits and their hats for latrines, being denied buckets by the Japs. Between 3 and 4 in the afternoon the Oryoku Maru edged close to shore. The captain sent down word that he was going to disembark all passengers. The American prisoners would be disembarked, too, as soon as guards were arranged on shore to keep them from escaping. (Tomorrow: Yanks Strafe Yanks.)

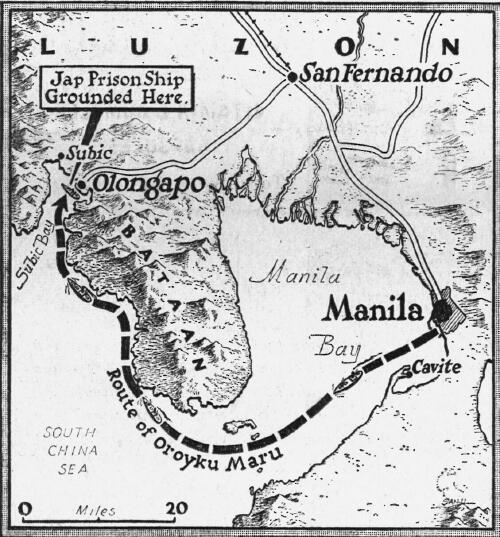

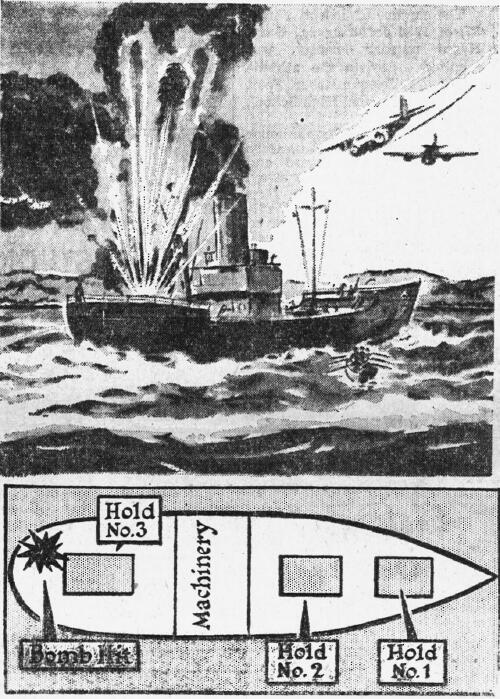

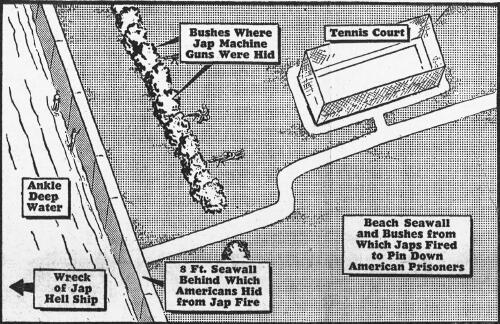

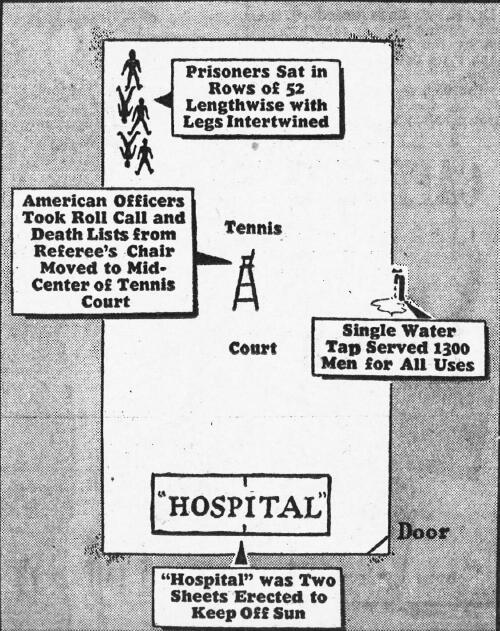

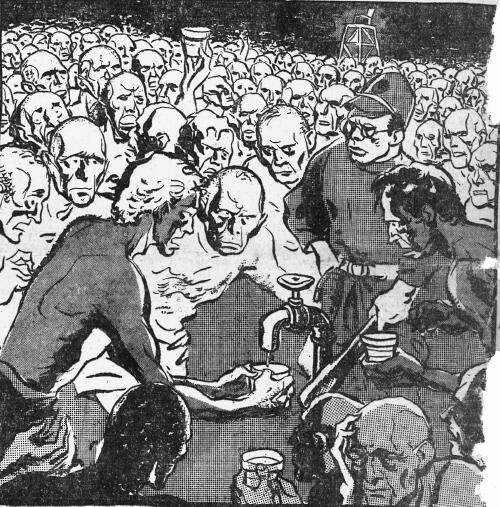

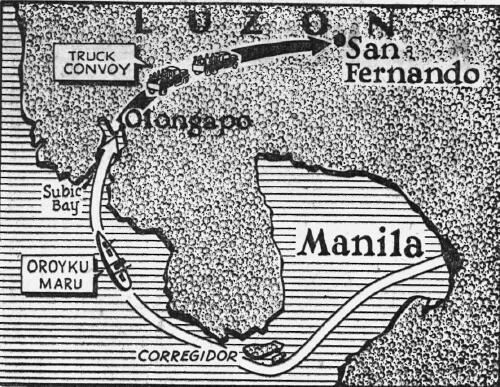

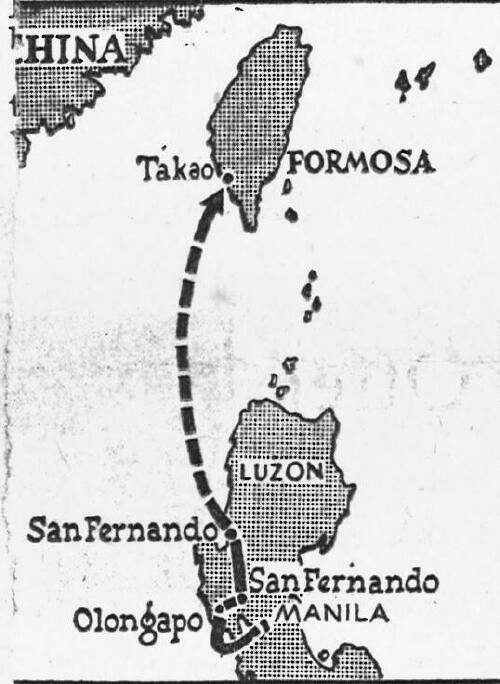

CHICAGO DAILY NEWS. Tue., Nov. 13, 1945. Death Cruise: Yanks Bomb YanksCHAPTER 4G.I.s on Jap Hell Ship Victims of StrafingMore than 30 Lose Lives As Explosions Fire CraftThis is another in a series of articles on the Cruise of Death -- 49 days of filth, starvation and madness aboard Jap hell ships transporting some 1,600 American prisoners from Manila to Japan. Three hundred were alive when it all was over. The survivors' stories were gathered in prison camps, rest camps, aboard hospital ships and at U.S. Pacific bases.BY GEORGE WELLER. Daily News Foreign Service. Battered by Yank planes, the Jap hell ship Oryoku Maru, her three airless, stinking holds jammed with some 1,600 American prisoners, was aground off Olongapo Point of the island of Luzon. It was December, 1944, and the prisoners, heroes of Bataan and Corregidor, were on their way from Bilibid Prison in Manila to Japan. Already they had spent more than 24 hours in the holds and many had died of heat, lack of air or at the hands of men driven insane. They were hungry, thirsty, fouled with their own filth. They had been told they would be put ashore from the damaged ship, but they waited hours until it was refloated. Discipline, partly restored during the day, again began to crack. About 10 p.m. the Oryoku moved inshore and began to discharge passengers. The Japs, seeing the American dead stacked on deck, feared the prisoners might try a break for shore. The Americans, equally fearful that the unbalanced men might overpower them and rush the ladders leading from the holds, posted guards there. Some did try. A Navy Lt. O'Rourke took out his prayer book and read a few words. Suddenly he began tearing the pages out and scattering them around. Then without warning he dashed for the ladder. He was caught before the guard above could shoot him and tied to the ladder until he quieted down.  Three Shots -- And Death Pharmacist's Mate "Chips" Bowlin eluded his friends and scaled the ladder. There were three shots from above. Bowlin never was seen again. Cmdr. Frank Bridget, in charge of No. 3 hold, shouted for order until he was hoarse. Some obeyed. But others could hear, or imagined they heard, men plotting against them in the darkness. They unclasped their knives. Chief Pharmacist's Mate D. A. Hensen worked his way across through the foul and steaming aisles to a little cluster of chief warrant officers. "Look," he said, "I've lost my nerve. The fellows over in my bay are going to kill me." His friends told him he was talking nonsense. In the morning he was found dead; his stomach slit open. AFTER THE Oryoku dropped anchor almost no air came down the hatches, which were about 14 by 14 feet. There were no ventilators. Animals could not have been shipped under such conditions and lived. Then, in the last hours of darkness of the second night, came the good news that the men were to leave the ship, on which nearly 100 had died. The Oryoku Maru's steering gear had been broken by the persistent strafing, and she had become unmanageable The prisoners were told to take their pants and shirts, messkits and canteens. And they were to wear no shoes -- to discourage escape once ashore. First 25 Men Leave the Hold The Oryoku Maru's steering 300 yards off Olongapo Point, Chief Boatswain Clarence H. Taylor of Cloverdale, Va., and Long Beach, Calif., took the first 25 men out of the hold. The Japs signaled that the prisoners were to be used as oarsmen. Taylor took six men and himself as the first boat crew. There were eight Japs in the first boat with him. "As we got in," said Taylor, "I heard the sound of airplane motors. I looked up and saw 12 American fighter-bombers circling for their dive." The lifeboat shoved off. The first wave of planes dropped their bombs, small ones. The Oryoku Maru began to list. ANOTHER PLANE selected Taylor's lifeboat for a strafing job. "What happened was the most lace-edged example of selective strafing I ever saw," said Taylor. "Of the eight Japs, six were killed. "We looked straight into the faces of those machine guns, firing just 18 inches apart. "And as I sat in the stern the Jap on my right was hit in the face and his whole head simply disintegrated, and the Jap on my left was hit in the chest and body and died instantly." The oarsmen were unharmed, but the lifeboat turned over and two of the Americans were non-swimmers. They stripped the dead Japs of their lifebelts. Next Wave Comes Over As Taylor lay on his back, striving to rest before starting for shore, the next wave of American, planes dived on their target. He said a bomb hit the aft hold just when the bodies of those who had suffocated during the second night were being removed. The bomb rained splinters into the hold full of naked men. The iron girder supporting the hatch planks blew into the hold, braining several men. There was a wild, uncontrollable rush for the ladder.  "I SAW THE first man get it," said Maj. F. Langwith Berry of Burlingame, Calif., taken on Bataan with the 86th Field Artillery. "He fell back dead in my arms. I jumped out of reach of the Jap fire." Suddenly a yellowish haze began to appear in the bays and a smell of smoke. "She's on fire," yelled someone. "Let's get out of here!" Chief Boatswain Jesse E. Lee, San Diego, said, "I remember the big yellow flash and the hot blast of the explosion. A lieutenant was as full of holes as a pepper shaker. Many more were dead. The slop buckets burst and there was excrement all over the bodies." Prisoners Find Guards Gone The prisoners tried the ladder, found the guards gone and began pouring out. There was brown sugar spilled on the deck and they gulped it. Others ransacked the ship for clothes and food. They got little of either. Some of the wounded got a shot of morphine from Lt. Cmdr. Clyde Welsh, Chicago. Once over the side, the cool water, sucked into the pores of their parched bodies, did much to revive the men. THE JAPS had gotten off in lifeboats. Now the water was filled with swimming Americans. They waved to the Yank planes and were not strafed but possibly as many as 30 died reaching for the shore. (Tomorrow: The prisoners learn there is hell on land as well as on shipboard.) CHICAGO DAILY NEWS. Wed., Nov. 14, 1945. Death Cruise: From Agony on Hell Ship to Terror in the SeaCHAPTER 5Japs Rake Swimming Yanks with GunfireTrain Machine Guns on Helpless Men Trying to Reach ShoreBY GEORGE WELLER. Daily News Foreign Service. The Oryoku Maru, Jap prison ship carrying approximately 1,600 Americans from Manila to southern Japan, had been so badly battered by American planes that she was forced to land her passengers on Olongapo Point, Luzon. Nearly 100 of the Americans already were dead from horrible conditions in the ship's three holds, into which they had been jammed. Suffocation, hunger, thirst, madness -- and American bombs -- had taken their toll. When the order to leave ship came, the men had plunged into the water and struck out for land. The first to reach shore found that there was no true beach, but ankle-deep water below an 8-foot sea wall. A few mounted the wall to lie exhausted in the sun. They had hardly fallen flat when a machine gun opened up on them. The shore was in the hands of the notorious J.N.L.P.'s, the Japanese Naval Landing Party, a kind of shock marines. They had a machine gun in bushes about 200 yards from the sea wall.  Lt. Col. Curtis Beecher of Chicago and Saratoga, Calif., a vigorous gray-haired marine, "who looked like Victor McLaglen," as one prisoner said, took quick command of the sea-wall situation. He ordered the strongest swimmers to plunge in again and help those who were struggling. He dived in himself and brought in about half a dozen. No Escape For Swimmers One or two men had afterthoughts about the wreck, swam all the way out again, filled up on brown sugar spilled on the decks and swam back. Others tried to escape by swimming to points farther down the coast but they were rounded up. TEXT MISSING ...........seemed to get the idea. He waggled his wings and flew off. Finally the Americans were allowed, after a parley with the Japs, to rest in the sun, on the seawall. Two Marine officers, Maj. Andrew J. Mathiesen of Los Angeles and Lt. Keene, a graduate of South Carolina's Citadel, approached the J.N.L.P.'s and explained that the Americans had been without water for two days. There was a small faucet near the Japanese positions. The Japanese allowed them to go in five-man details to the faucet. AROUND NOON the barefooted, sunburned Yanks were told to march. Two men helped each of the wounded. With bayoneted rifles and clubs the J.N.L.P.'s were placed at intervals of about 30 yards along a crooked line of march about a half mile long to a tennis court about 500 yards back from the seawall. By about three p.m., the last of the bearded and bandaged men hobbled into their new prison. It was a single concrete court not far from an old Marine barracks, and undoubtedly some of the elder officers had played there in the happy days when service life had been a country........... TEXT MISSING ........Lt. Col. Beecher, whose forward hold on the ship had suffered greatly, but not so much.  Beecher, sitting aloft in the referee's chair, had great difficulty establishing quiet and order. Finally the problem of arranging over 1,300 men on a single tennis court was solved. The prisoners sat in rows of 52 men each, their knees drawn up to their chins. Oryoku Maru Sunk by Bombs The prisoners had barely got seated when they had reason to jump to their feet. Their bombs sank the Oryoku Maru. A wave of three American planes came over. (At the time of Japan's surrender, she was still lying in the same place off Olongapo, with some 15 feet of water over the tip of her mast). Said one Navy man, "we enjoyed the whole scene immensely." On a 15-foot wide strip the prisoners established their "hospital." Lt. Cmdr. Clyde Welsh of Chicago took over. The "hospital" consisted of two sheets and a couple of raincoats stretched to give protection from the sun. The Japs furnished no medical supplies and naturally the half-clothed Americans had none. THE FIRST major operation was the amputation of the arm of a Marine corporal named Specht by Lt. Col. Jack W. Schwartz, surgeon of the famous Hospital No. 2 on Bataan. There was no anesthesia, no scalpel. The arm was removed with a cauterized razor blade. (The Marine lived for five days on the exposed tennis court, then died.) The overpoweringly prevalent disease was diarrhea and dysentery, and there was no drug to check it, nor even food. The Japs said they had none for the Americans. (Tomorrow: The men go to a new camp and get their first hot food -- rice.) CHICAGO DAILY NEWS. Thu., Nov. 15, 1945. Death Cruise: Sun Burns Naked G.I.sCHAPTER 6Japs Give Prisoners' Water by Spoonful1,300 Men from Hell Ship Jammed on Tennis CourtThis is another in a series of articles on the Cruise of Death -- 49 days of filth, starvation and madness aboard Jap hell ships transporting some 1,600 American prisoners from Manila to Japan. Three hundred were alive when it all was over. The survivor stories were gathered in prison camps, rest camps, aboard hospital ship and at U.S. Pacific bases.BY GEORGE WELLER. Daily News Foreign Service. It was hot on the concrete tennis court on Olongapo Point, Luzon. There were packed some 1,300 American prisoners out of 1,600 who had left Manila some three days before on the Jap hell ship Oryoku Maru. Heat, thirst, suffocation, wounds and insanity had taken their toll in the jammed, filthy holds of the ship. But American planes had taken revenge of a sort by first damaging, then sinking the craft. So the men were ashore again, but no better off. They had stripped in the fetid holds of the ship and in their hurry to leave the battered vessel, most had left their pitiful apparel behind. Now on the open tennis court the sun showed no more mercy than did the Japs. The prisoners were in desperate condition from thirst. They could easily have absorbed four to five quarts of water per man. But the Japanese denied them any other water than that from a single faucet. An uncertain trickle came from it. They caught it carefully in canteen cups, and served it with spoons. It worked out to four spoonfuls per man, with the faucet running constantly. Its stream grew thinner and thinner.  Maj. Reginald H. "Bull" Ridgely, a marine so named for his thunderous voice, began with Lt. Col. Curtis Beecher of Chicago to try to take the roll from the referee's platform, which had been moved to the center of the court. It was a long and tedious task, with something particularly aggravating about it to the men who sat in the court waiting for night to fall. A name would be called. No answer. "Well, anybody know what happened to him?" Half the men were not listening, trying in some makeshift way to better their position. "Well, doesn't anybody know what happened to him?" I Believe I Saw Him with the Dead A voice would say, "I think he passed out last night. I believe I saw him with the dead on the deck, way down under." As soon as there was a definite assertion, it would give birth to contradictory ones. "The hell you did! He was in the next bay to me. A bomb fragment got him." And from someone else, "How could a bomb have got him when I saw him swimming away from the ship?" At that moment the missing man might walk in from the latrine outside. Or the questioning might go for minutes longer, establishing something or establishing nothing. As nearly as can be pieced together, one Chicagoan was known to have been killed, and another did not answer the roll. They were: Maj. Irving Mandelson of 24th Field artillery, son of a Chicago restaurateur, killed in Oryoku bombing. Ensign George Petric, former Marquette football player. As the sun went down, the concrete suddenly lost its heat and grew cold. Men whom the sun had skinned red, men who had been putting their hands on their burning shoulders, now were shaken by chills and hugged themselves.  LESS THAN a third had shoes; many had only shorts or pants; a few were totally naked. Some of the Formosan sentries had been guards also at Cabanatuan prison camp and were known to the prisoners. These "Taiwanis" threw a couple of shirts over the fence, and pushed some casaba melons through the wire and a few cigarettes. Some men were too weak to sit up in the rowers' formation of 52 men packed in a row, devised to fill the court, and fell over. Some lines therefore devised a method of all 52 lying down together on the right side, intertwined, and then all 52, at the word "Turn over, boys," changing the position to the left. Cold, thirsty and, hungry and frequently brought to their feet by the prevailing disease, diarrhea, few slept. The morning brought a few warming minutes that were neither chill night nor torrid day. Again there began the tedious calling of the roll, a rite always done centrally from the referee's chair, which took nearly two hours. About six more men had died during the night. A burial detail was named; the dead bodies were stripped of clothing. They were buried in an improvised cemetery down by the sea wall. The second day in the tennis court the prisoners received their first meal: two tablespoonsful of rice, raw. Their standard measure had become the canteen cup for a line of 52 men, and the tablespoon for each man. They asked Mr. Wada, the Jap interpreter, why they could not have more food and water. There was plenty of rice and water in the Jap naval landing party barracks nearby. The little hunchback would not give them permission to go for the water. As for the rice, he said that he could not get that for jurisdictional reasons -- while aboard ship they were in the care of the Japanese navy. Now that they were ashore, they were under the army. Men Fight the Burning Sun To fight the sun the men tore off the bottoms of their trousers to make caps, and finally they got permission to move the worst wounded from the surface of the court to some shade trees outside. On the fourth day from Manila they got their first food ashore. On the fifth, as though to off-balance such generosity, there was no food morning or noon and a light supper of two tablespoonsful of raw rice. Eventually some clothing came out from Manila. There was enough to tantalize, not enough to cover. THE SIXTH DAY on the open tennis court, Dec. 21, a truck convoy arrived. The prisoners were taken to San Fernando Pampanga, stopping often under trees whenever airplanes were heard. The first convoy unloaded at the prison, which had been filled with Filipinos; the second unloaded at the theater. The prisoners were in good spirits. They had lost strength, but they had gained eight days delay from Japanese, and Gen. MacArthur was still on the way. The prison yard at Pampanga is about 70 feet by 60, and a lemon tree grew in the center. The lemons lasted about 15 seconds after the first prisoners entered; in five minutes most of the leaves were eaten as well. There were two cell blocks, a single story high. The elderly officers and the sick were housed in them. The other prisoners lay down as they had in the tennis court in the sun. There had once been toilets, but they were long since broken. The latrine became the open culvert, six inches deep, which ran around the yard. "The flies," says one officer, "came from all over Luzon." About 800 were jammed into the prison, and the other 500 into the dilapidated theater. But still the prisoners' hearts were light. For the first time they had hot food. It was only rice and it was brought in on two big pieces of corrugated iron roofing, but it was hot and filling. And they had water, too, all they could drink. What if they had to fill their canteens at the toilet intakes? It was water, and brought back life to their beady, shrunken stomachs. (Tomorrow: Christmas -- and leaves for breakfast.) CHICAGO DAILY NEWS. Fri., Nov. 16, 1945. Death Cruise: Merry Chree-eestmasCHAPTER 7Yule Dinner Consists Of Rice, Dirty WaterLast Hope Fades as Japs Herd Yanks on Ships AgainBY GEORGE WELLER.Daily News Foreign Service. After eight days of their tortured odyssey from Manila to Japan, 300 American prisoners were dead and the toll was mounting daily. But those remaining found cause for hope. At least the hell ship into which they had been jammed had been sunk and they were back on land at San Fernando Pampanga, on the island of Luzon. And there was food and water -- cooked rice served on a sheet of corrugated iron and water from toilet intakes -- but to parched and starving men like the manna from heaven. On the night of Dec. 23, 1944, four Red Cross boxes came down from Manila. For 1,300 men the amounts of needed drugs were minute, but they gave hope. On the same night several of the most ill were evacuated back to Bilibid Prison in Manila.  AT 3 A.M., Christmas Eve, the men were routed out of the prison and theater, where they had been held, and marched to the railroad station. An aged locomotive, whose multiple bullet holes testified to what the American planes were doing to Japanese rail traffic, awaited them with a string of inadequate, 26-foot freight cars. The wounded were piled on top. The merely ill were packed in below. There were 107 men in and on one car. Mr. Wada, the Jap interpreter, soon explained why the wounded had been placed on top. "If the American planes come," he said. "you must wave to them and show your bandages." The train, thus "protected," was loaded with ammunition and supplies.  Filipinos Shout, 'Merry Christmas!' The heat in the closed boxcars was so terrific that conditions soon equaled those aboard the prison ship Oryoku Maru. But outside they could hear the Filipino urchins yelling to the wounded on top, "Merry Christmas! Merry Chree-eestmas!" As night fell the train was still crawling northward. At 3 a.m. it reached San Fernando del Union, on Lingayen Gulf. The filthy, cramped men tumbled forth and slumped on the platform in sleep. It was Christmas morning. At daylight the Americans were marched to a single-story trade school on the outskirts of the town. A bush with green leaves and red flowers stood by the gate. They ate the leaves by handfuls for breakfast. The menu of their Christmas dinner was one-half cup of rice and one-third cup of dirty water. About 7 p.m. they were marched three miles -- nearly all were bare-foot -- over a coral-shell road to a beach overlooking the Jap anchorage. The sand was bitter cold. The naked men shivered and pushed against each other for warmth. At least two died. It was bitterly clear that they had been moved once again beyond hope of rescue by Gen. MacArthur. They were going to Japan. THE OFFICERS of the 200th Coast Artillery, almost all outdoors men from New Mexico, began to plan an escape. They would steal a rowboat and make their way up the coast. But Lt. Col. John Luikart of Clovis -- who was to die within a week -- forbade the plan. He reminded them that the Japanese had shot six New Mexicans at one time on Bataan simply for deviating from the line of the death march to Camp O'Donnell. "You cannot expose the lives of these other prisoners to reprisals," he reminded them. Again the burning sun came up. Again the skins of the weakened men began to curl with sunburn. Cmdr. Frank Bridget begged the Japs for water. A rice ball was issued for each man, but discipline was cracking again. Some got two; some got none. Bridget and Lt. Col. (now Col.) Curtis Beecher of Chicago then obtained permission for the men to enter the water and bathe their blisters. 5 Minutes In the Water They were allowed Jive minutes in the water. Many were so dehydrated that they scooped the salt water into their mouths. An Army captain dashed into the water, drinking like mad. The Japanese raised their guns to fire; but he was pulled out in time. Finally the Japs issued water: one canteen cup for 20 men. It worked out to four tablespoonsful for each thirsty mouth. But there was a rotation. After 90 minutes more in the sun you could have another four tablespoonsful. Lt. Toshino, in charge of the prisoners, and the hunchbacked Mr. Wada had seen how the American planes spared the prisoners twice before. Here at Lingayen they put this immunity to use. "We want you to be warned," said Mr. Wada. "You are sitting on a gasoline dump. If we are bombed -- well---." All that day they did not believe him. But that evening soldiers dug drum after drum of gasoline from directly under them. AGAIN they lay down in the cold sand, shivering, thinking of Christmas at home, too hungry, thirsty and cold to sleep. Somewhere between midnight and dawn the Americans were marched to a dock, loaded with supplies. It was still dark, and the hungry prisoners plundered some of the boxes. The New Mexican artillery officers found some bran and a little dried fish, which they parceled out among those who had shirts in which to conceal it. The Japs were suddenly in fearful haste. "Speedo!" shouted the guards, "Speedo, speedo!" Rifle butts and the flats of their swords enforced their orders. The sun was just coming up as the prisoners climbed on, on sunburned feet, the iron side-ladder of their new vessel. Good Reason For Japs' Haste All this haste was for a good reason. American submarines had become specialists in night attacks. And there always was the danger of bombers by day. At Lingayen, however, there was some safety from planes because of the distance from U.S. bases. The Japs now wanted to get out at dawn and widen the aircraft range as much as possible the first day. Two freighters were leaving, a big one of about 8,000 tons marked "No. 2" [Enoura Maru] on its super-structure, and another of about 5,500 tons marked "No. 1" [Brazil Maru] on its funnel. The first 1,000 men were crowded aboard "No. 2" in the midships hold, which had two levels. The remainder, some 234, were hustled aboard "No. 1". They sailed on the morning of the 27th. The last cargo "No. 2" had carried war horses. "The hold where we were," says a prisoner, "was like a big floating barn, full of horse manure and the biggest, hungriest horse flies I ever saw. They covered our mouths, ears and eyes. We smelled already and the smell drew them." IT WAS the Jap practice to save the urine of the horses for some chemical use, bringing it back to Japan in the bilges of the ship. "An overpowering smell like ammonia came up from the bilges," the men said. There was a ventilating system to keep the horses alive, but with Americans in the hold the Japs shut it off. The pit on "No. 2" was about 60 feet square, with bays or shelves 10 feet deep on two sides and bays about 4 feet deep on the other sides. The horses had left scattered feed in the crevices of these stalls. The prisoners scraped up the remnants, mixed them with the bran stolen on the dock, and ate the mixture. 'All We Want Is a Chance' Lt. Col. Kenneth "Swede" Olson, a Regular Army finance officer who had been camp commandant at Mindanao, boldly faced Mr. Wada. "These men are hungry and thirsty," he said. "They are dying. Sick men won't be any good to you, Mr. Wada. Dead men won't help you. Give us a chance. We're not afraid to work for our lives. All we want is a chance." Finally the prisoners were given rice and a quarter canteen cupful of hot soup. But the Japs would not allow them to keep the rice buckets long enough to pass around. So they dumped out the rice on dirty raincoats and on the manure-scattered pit. "The lineup was something to see," says one prisoner. "We were barefooted, bearded, dirty and full of diarrhea. We ate from our hats, from pieces of cloth, from our hands. You would see an officer who once commanded a battalion with a handful of rice clutched against his sweaty, naked chest so the flies could not get it, eating it like an animal with his befouled hands." (Tomorrow: Death moves swiftly among the men on two Jap hell ships.) CHICAGO DAILY NEWS. Sat., Nov. 17, 1945. Death Cruise: Jap Medics Just Let Yanks DieCHAPTER 8200 Are Killed By U.S. BombsSuffer All Sorts of Horrors On Way to Nip PrisonsBY GEORGE WELLER.Daily News Foreign Service. After days of bombings, hunger, thirst, all the horrors and indignities to which men can be subjected, two groups of American prisoners were definitely on their way to Japan. They were being taken from the Philippines -- away from the last hope of rescue by Gen. MacArthur's advancing forces. About 1,000 of the men were aboard a freighter known only as "No. 2" [Enoura Maru]. The remainder, 234, were aboard "No. 1" [Brazil Maru]. Again their quarters were airless holds of stench, disease and terror.  It was Dec. 27, 1944. Again death was moving quietly among them. A man died almost every hour of dehydration, diarrhea or old wounds. When a man died his body was stripped of usable clothing and hoisted up. Tying up the bodies was the job of boatswains like Jesse E. Lee of San Diego. "I would tie a running bowline around the feet of the corpse and a half hitch around his head, and then say, 'All right, take him away,'" he recalled. "Then he would rise up out of the hold, and his friends could see him for the last time against the sky as he went out of sight." Chaplain Blesses Dead Prisoners Most of the chaplains were by this time beyond doing any duties. However, a Catholic Army lieutenant, Father William "Bill" Cummings of San Francisco and Ossining, N.Y., who in a sermon on Bataan had first uttered the words, "There are no atheists in foxholes," often managed to say a few words of blessing as a body rose through the hatch. As the ships drew away from the Luzon coast it began to grow bitterly cold. And as the deaths increased the Japs ruled that only when six or eight bodies had been collected could there be a general hoisting of corpses. The horse troughs around the hold had been turned into latrines. "You could watch a single fly go from the latrines to the bodies, and then from the bodies to your rice," said a prisoner. THE 204 MEN on "No. 1" got no food at all for the first two days. The guards diverted themselves by dropping cigarettes through the hatch to watch the Americans scramble. Every scrap of food on hand as rationed. Their first food as the leavings from the guards -- a teaspoon of rice per man. Lt. Col. "Johnny" Johnson took a teaspoonful to the commander of the guard. He said, "If we must go on like this, my men will all die." The commander replied, "We want you to die." New Year's Feast: Jap Hardtack However, the Jap crewmen sold a kind of cheap rock candy to the prisoners in return for rings and fountain pens. The convoy reached the harbor of Takao, Formosa, on New Year's Day. In celebration of safe arrival the prisoners aboard "No. 1" received five pieces of hard-tack each, their New Year's feast. About a dozen men had died on "No. 1" and a somewhat larger number on "No. 2."  AFTER THREE or four days in Takao harbor, the Japs decided to put the two parties together aboard "No. 2." After 24 hours without food or water the smaller party was jammed into the midships hold of "No. 1" and a somewhat larger number on "No. 2." The next day the Japs decided to open a forward hold, where about 450 men under Capt. (now Maj.) Arthur Wermuth of Chicago, the "One-Man Army," were transferred. The 37 British prisoners who had shared the horrors of the trip were sent to join their compatriots in Formosa's camps. About 8 a.m. Jan. 6 there was a sudden crackle of anti-aircraft fire. Then the bombs from a few planes based in China began to fall. The first hit the side close by the forward hold, and the ship rolled with the blow. The others -- two or perhaps three -- hit close inboard. A light warship tied alongside "No. 2" made an inviting target. Capt. Wermuth Takes Charge The first bomb not only tore at the side of "No, 2," it ripped holes in the partition between the two holds. "We looked through the holes," said Theodore Lewin, a big broken- nosed soldier of fortune who had been a reporter in Los Angeles on the Huntington Park Record and proprietor of an offshore gambling ship. "We could see bodies, there in the forward hold, all stirred up and scrambled. Almost nobody was even moving. "In our own hold the whole place was covered with bodies. " "Then from the forward hold Capt. Wermuth yelled up, 'I'm taking charge here. Get us some stuff for the wounded, quick.' " "WE'RE GOING to need the last clothing you have for bandages, boys," announced Lt. Col. James McG. Sullivan of San Francisco, a medico. "Tear off your pant legs and shirts. If you're cold, get a sugar sack. "We've got to save these men." THE SIGHT of the wounded in the middle hold was peculiarly unbearable. The fumes coming from the bilges had turned the men's hair an unearthly yellow. In the hold amidships, from which comes the only coherent accounts of what happened, there were about 40 killed and about 200 wounded. In the forward hold, which resembled a human butcher shop, more than half the prisoners, more than 200, had been killed. Many of the rest were gravely wounded. Japs Do Nothing To Aid Wounded The Japs were in a civilized harbor, with doctors, hospitals, barges and all other medical services at their disposal. But the first day nothing whatever was done. The second day a small detachment of Jap Red Cross corpsmen arrived. They did not even attempt to enter the forward hold. They handed out some medicines in the midships hold, and went away. The stench was beyond breathing, but for two days the Japs would not allow the bodies to be moved. WHEN THEY did, it was a task almost beyond the strength of the survivors. These men had lost as much as 10 pounds each. They had not had a true meal in many months; they were battle-shocked and they had no apparatus. In addition, the bodies they had to move were those of their comrades. AND YET they had not wholly lost the American's last resource -- his humor. As they stripped the bodies of clothing, as they tugged them and stacked them; they laughed at what had happened to a rice-and-latrine detail that had been on deck when the bombs struck. Their guard, a Formosan named Ah Kong, had hardly heard the whistle of bombs when he dropped his rifle, ran into a passageway and huddled there. The Americans were scared of the bombs, but more scared of something else: that the other jittery guards, seeing them without Ah Kong, would shoot them down. 300 Dead Around Wermuth So they picked up Ah Kong's rifle and poured pellmell after him into the passageway, where they returned their panting sentry his weapon, pointing it back as usual at themselves. "We'll never forget," said one member of this detail, "when Ah Kong allowed us to walk forward and look down for a moment through the twisted hatchway of the forward hold. "We could see Wermuth standing there, looking around trying to get his bearings. There seemed to be at least 300 dead around him and about 100 wounded. "About 50 men who were whole were still walking around, dazed." LT. COL. (now Col.) Curtis Beecher of Chicago took charge in the hold amidships, Wermuth forward. Among the men known with reasonable definiteness to have died in the Takao bombing were Capt. Robert A. Barker of Springfield, Ill., an anti-tank officer of the 31st Infantry; Capt. J. E. Brunette of the field artillery from Fort Sheridan, who was engaged to a girl in Santo Tomas prison, Manila, and Lt. Cmdr. Clyde Welsh, a medical officer from Chicago. (No present address of relatives of Cmdr. Welsh have been found here. -- Ed.) (Monday: American bombs kill 350 prisoners in Formosa.) CHICAGO DAILY NEWS. Mon., Nov. 19, 1945. Death Cruise: Dead Go AshoreCHAPTER 9Survivors Load Buddies For Burial on FormosaWire Cargo Nets Transfer Naked Bodies Into BargeBY GEORGE WELLER.Daily News Foreign Service. The strong in mind and body, the smart and the brave among the American prisoners being transported from Manila to Japan were still alive after weeks of hunger, thirst and almost indescribable horror. But in the harbor of Takao, Formosa, death laid a heavier and more ironical hand on the dwindling but still gallant band. Three hundred and fifty died in one day -- from a bombing raid by American planes based in China; and from callous Jap treatment that followed. For two days the dead were not moved. Then a barge appeared alongside. The dead were going ashore in Formosa. In the forward hold, Capt, (now Maj.) Arthur Wermuth of Chicago was forced to haul the bodies like fagots and swing them through the hatch by dozens, hugged by a wire cargo net like bunches of asparagus. It was hard to keep track of who was dead. Many were unrecognizable.  FOR THE UGLY job of loading the dead there had been little rivalry. The survivors were weak and extremely thirsty. Though the ship was in harbor, the Japs kept saying, "No water -- we have no water." Then came the command: "We need 30 men to go ashore for burial duty with these bodies. Who volunteers?" Almost every man who could totter to his feet volunteered. The offer was not strictly without self-interest. There was hope that, once ashore, a man could fill up his body with water and renew his thinning blood. At length the barge, overloaded, moved toward shore. There, at a breakwater, the men found that they were too weak to carry the bodies ashore. They attached ropes to the naked feet and dragged them to the point where the breakwater met the sand. There they laid them in rows. It was a coal dumping yard, and they left the bodies there on the beach that first night, beside the coal. The second day was the same. Each night the burial party drew up and gave a military salute, before returning to the ship. The third day they took all the bodies back to a Jap crematorium near a shrine and rendered them into ashes. Prayer Brings First Silence By now an evening prayer had become a part of their simple routine. Of the estimated 16 chaplains in the party, both Protestant and Catholic, only three were to live to Japan. The strongest seemed to be the Army priest, Lt. "Bill" Cummings of San Francisco and Ossining, N. Y. One Navy man says, "I shall never forget the prayer that Father asked that first night after the bombing, when the Japs would not let us move the bodies. Before, many men had paid no attention, but this night the minute he stood up there was absolute silence. I guess it was the first real and complete silence that there had been since we left Manila. Even the deranged fellows were quiet. "And I remember what his opening words were. He said, 'O God -- O God, please grant that tomorrow we will be spared from being bombed.' "The last thing he did was to lead us in the Lord's Prayer. I think every man there, even the unbalanced ones, managed to repeat at least some of the words after him." THE PRISONERS kept alive by partly trading with the Japs and partly by stealing sugar from the bottom of the midships hold. The Japs set every kind of guard, but the prisoners always managed to trick them. Two of the ablest sugar thieves were a lieutenant in the geodetic survey of the Coast Guard, who teamed up with a Catholic Navy chaplain, Lt. McManus. Finally they were caught. The guards slapped them, knocked them down with rifles and kicked them systematically. The Coast Guard lieutenant, seeing that the chaplain was going under fast, protested that he alone was responsible. McManus was released. The officer, after another hour's beating, was pushed back through the hatch. The sugar thefts went on. Finally Lt. Toshino, in charge of the prisoners, and Mr. Wada, the interpreter, came to the edge of the hatch, "Who has stolen the sugar?" demanded Mr. Wada. No answer. Then came a stiff announcement. "Unless the thieves give themselves up immediately, we will cut off all rice and all water from both holds." The Call For Volunteers The silver-haired Lt. Col (now Col.) Curtis Beecher called a general meeting. He said, "This isn't a question of finding who has been taking the sugar. It's a matter of saving the lives of men who will die unless they have rice and at least a little water. "We've got to have two men who are willing to go up and offer themselves as hostages for all the others. I don't have any idea what Toshino and Wada will order done to those two men. They may have them shot. I just don't know. "The only thing I can promise is this, if they survive whatever the Japs do to them, I will see to it that they are taken care of and don't go without food the rest of the trip. THERE was a husky English sergeant named Trapp aboard who had not gone ashore with the 37 Britons earlier. He had known several of the 4th Marines during his duty in China, and he had made new friends on the trip from Manila. And there was a husky medical aidman who, had qualified for honors on Bataan by carrying a wounded man on his back for 13 miles. He was an Ohioan, Sgt. Arda M. "Max' Hanenkrat of the 31st Infantry. Trapp and Hanenkrat volunteered. Waiting For the Shots Everyone waited, penned below, listening for the sounds of such volleys as had already killed several prisoners. None came. Later the men were seen, marked with blows and faint, kneeling between guards. Every time one reeled and fell over the Japs would slap him to consciousness again. Eventually they were pushed back into the hold. They lived to clamber aboard the boat that look them to Japan. But in the end these two great-hearted men both died. The ship, "No. 2," was too battered to reach Japan. The morning of the 13th, two weeks after the arrival in Takao and a week after the bombing, Lt. Toshino ordered the remaining men to move to another ship. (Tomorrow: Another ship, and the sufferings grow worse as midwinter cold strikes the men.) CHICAGO DAILY NEWS. Tue., Nov. 20, 1945. Death Cruise: Thirst Kills YanksCHAPTER 10Only 900 Men Alive Out of 1,600 AboardBrutal Japs Admitted They Didn't Care if Prisoners DiedBY GEORGE WELLER.Daily News Foreign Service. The last lap of their long arid tortured voyage was about to begin for the dirty, wounded; sick American skeletons who had left Manila for prison camps in Japan. They had suffered almost to the limit of endurance, but their tale of horror had not yet been spun out. Many were dead -- some from bombs dropped by other Americans who had no way of knowing. The others were dead from the brutalities of the Japs -- who admitted they did not care. Between 800 and 900 men were now alive of the more than 1,600 who had marched out of Bilibid a month before. Many more were at the gate of death. To move them was to doom them. But the Japs wanted them moved to another ship there in Takao Harbor, Formosa. Men Moved Like Cattle There were intestinal hemorrhages, extreme shocks, amputations: how could such men be moved? But move them they did -- trussed like cattle or strapped to planks. "In a way this was the most terrible job of all" said one officer. "For the first time we had to cause pain to ourselves and we could not avoid it. "What I remember most clearly was the smile on the face of Mr. Wada, the Jap interpreter, as he watched us." APPROXIMATELY 14 men who reached the new ship never saw its hold. They died on its decks and were buried at sea. On the new ship [Brazil Maru], an undersized freighter, the shrinking party was again forced into a single hold. The bays were about 15 feet long by about 10 feet deep. Each bay accommodated about 20 men. Two positions were possible: To set with legs extended, or to lie down with knees drawn up. Standing, or lying down at full length, was impossible. Rapidly, though, the party diminished, the Japs always managed to see that their pits were smaller than normal for their numbers. The hold was the next to the last aft.  AFTER SUNDOWN Jan. 13 the ship slipped out of Takao. Her course did not turn toward Japan, but China. By now it was apparent that only the strongest would live. The little food was carefully rationed, but not equally. The medical corpsmen, who were doing most of the physical work, got more by common consent. And the details which carried the slop buckets on the decks had opportunities for trading not given to those lying below decks. Counts 47 Dead On First Day Out The death rate took a wild jump. George L. Curtis said: "I counted 47 dead in all on the first day out." It immediately grew colder. A few straw mats were in the hold, but only enough for about a third of the men. Friends tried to huddle together under a single dry mat, while the cold wind swept under them. From the first day a bitter draft began to suck through the hold. It came from the ventilator in the Jap quarters just astern, swept across the hold and up through the hatch. On this wind of death the lives of many Americans rode their way out. THE JAPS would not allow the ventilator to be closed, and so came pneumonia, a new visitor. A hatch in the center of the hold, covered with tarpaulin, led to the deck below and was never opened. It lay there, bare to the sky. The rain and later snow and hail fell on those who lay exposed on the hatch. It was terrible. The dead were piled there, and to be moved there meant that the food of those who might still be alive could no longer be spared for you. It placed your neighbor to the dead whom you would soon join. But Gene Ortega of Albuquerque slept on the hatch through all the voyage and is alive today. THE DYING men on the hatch were looked on covetously by the shivering men in the bays, who already were mentally dividing up their clothes. A medical committee for clothing -- itself grotesquely naked, a kind of skinny parody of such social committees at home -- was supposed to handle the equitable division of clothes. But men who died or were near death at night might be found naked in the morning -- and no questions asked. Japs Try to Kill Yanks by Thirst It was unmistakable from the beginning that the Japs had not lost their intention of killing their prisoners by thirst. The ship was just out of harbor and her water tanks should have been filled to the brim. But the prisoners got two to four spoonsful daily. The use ration was half a canteen cupful daily. "If you forgave the Japs everything else," said one survivor, "I cannot see how you could forgive the way they denied us water all the way from Manila to Japan." The Japs had no water to give, but they had plenty to sell. At the rear of the two passageways between the bays there were two open gratings. They were the trading center. By now the Americans had little left to offer. The keepsakes a man parts with last began to go. THE JAPS liked American wedding rings, the solid gold kind. A thick one was worth five canteens full of water. Annapolis and West Point rings, the most valued possession of the professional officer, were always bad seconds to wedding rings. They never brought more than four cigarettes, and an early glut brought them down as low as two. For a pair of shoes you could get two cans of tomatoes or salmon or a handful of tangerines. For a heavy Navajo turquoise ring Lt. Russell Hutchison, Albuquerque, N.M., gained two straw mats, enough to save his life and that of another officer. A wrist watch -- rare indeed -- bought an old rice sack.. Capt. William Miner saved his life and that of Maj. F. Langwith Berry of San Francisco by trading a fountain pen for a straw hat. 20 Prisoners Die Each Day As the freighter wound her way through the desolate islands off the Chinese rivers, hiding by night against prowling submarines, the prisoners began to die at the rate of 20 or more daily. A man whose husky constitution made him a body collector said: "Every morning was the same. The ladder guard would waken me and say that it was time to get busy. "I would take a small handful of sugar and swallow it for breakfast before I touched the bodies. Then I would slowly make the circle of the bays. "I DIDN'T make any pretense of being dignified or tender. I would just stop at the bay and put my head in and said, 'Got any stiffs in there?' "They might say, 'Yes, we've got a big one this morning.' 'Well,' I'd say, 'get him out to the edge here. I haven't got all day.' "Sometimes they would help me, but sometimes they would just say, 'Come on in and get him yourself.' "That would make me sore. I would dive right in there and knock them over until I got what I was after. "I'd haul him out. Nine times out of 10 he'd be stripped already and there'd be nothing for the clothing committee. "It must sound callous to say so, but death meant nothing to us. If you made it, you made it; if not, you died. "That was all there was to it." Watches Brother Die on Hell Ship Even in this filth, thirst and starvation, however, decency would send up timid occasional shoots. The Shirk Brothers, Robert and Jack, had been mining engineers in Manila when the Army gave them commissions. Jack fell sick first, grew worse, and finally the corpsmen saw that he would not live. They laid him out on the hatch, where he soon died. HAVING stripped his body, they were about tug it roughly to the "dead side" of the hatch, when a corpsman looked up and whispered: Hey, handle this one with a little extra care. His brother is watching us from that upper bay." When they had laid Jack Shirk with the others, Bob Shirk climbed painfully down. He stood looking at his brother, his matted head bowed. Perhaps he prayed. At length he shook his head slowly and went back to his own bay, where he too died. WHEN SNOW fell, the prisoners caught what flakes they could in their unwashed messkits, waving the kits back and forth under the hatchway like magic swords. So as not to miss any flakes, they sometimes had to pull the dying out of the way. Sgt. Maj. James J. J. Jordan, as tough at 53 as a bantam after 33 years in the rough world of the Marine Corps, said, "For the first time in my life, I was beyond knowing or caring what happened." (Tomorrow: The rest of the men left reach Japan.)

CHICAGO DAILY NEWS. Wed., Nov. 21, 1945. DEATH CRUISE: Hell Ship Ends TripCHAPTER 11435 Alive of 1,600 Who Started TripEven Nip Officials Shocked By Pitiful State of SurvivorsBY GEORGE WELLER.Daily News Foreign Service. Japan was near. The Americans on the Jap hell ship, Oryoku Maru, originally had fought to keep from going there, and later they had fought to stay alive to reach there. Most had failed. Of some 1,600 who had left Bilibid prison in Manila for what they thought would be a seven-day trip to Jap prison camps, about 1,000 had died. Death had come in many forms during the 49 days the trip did take. American bombs took some, thirst, illness, madness, starvation and disease took others. The pitiful handful left were hardly men. Once civilized beings, they now were little more than animals fighting the great, ultimate fight for survival. Ted Lewin, once a Los Angeles reporter and promoter, approached the new Yank commanding officer, Lt. Col. (now Col.) Curtis Beecher of Chicago. "What are you thinking about, colonel?" he said. "I was remembering a fellow I heard talk at the Explorers' Club in Chicago after the last war," said the gray-haired colonel. "He described how the Armenians made their march of death with the Turks driving them along. I was just wondering whether it could have been any worse than this." Beecher Tells Off Jap Interpreter For the theft of sugar, Mr. Wada, the Jap interpreter, threatened to cut off all food. "It doesn't matter," said Beecher wearily, "because if you don't give us some water and food we're all going to pass out anyway." The violent rages, the bloodsuckings and murders of the Manila-Olongapo trip were no longer possible. The men were too weak and broken in spirit. They belonged now to God or Fate.  LT. WILLIAM CUMMINGS still carried on his evening service. His chaplain colleagues were mostly gone. One, Lt. John E. Duffy of Notre Dame, was in a condition in which he insisted on being brought ham and eggs. Then came an evening when Father Cummings, 43, was unable to stand up. Weakened by severe dysentery and thirst, he never spoke again. Soon the Japs delivered him to the sea. Kills Himself With a Blow One man struck himself in the brow with a canteen and fell over. "We could not believe that there was any way that a man could commit suicide with a canteen," said one survivor, "but we saw it done." Cmdr. Frank Bridget, a tower of strength from the beginning, had been fading rapidly. He had an extreme case of .diarrhea, so acute that he sometimes moved in a daze. When death came, like many of the prisoners, he probably did not even know that he was going. IT WAS NOT all heroism. Not only was clothing stolen from the dying, but water from the healthy and well. "There were fellows who taught themselves how to slip down beside you while you were asleep, open your canteen and without a sound of swallowing drink all your water," said a survivor. "You would try to sleep with your fingers locked around the plug; it didn't always work." But there was also Lt. Col. Charles I. "Polly" Humber, a football hero at West Point, who shared his water with many others before diarrhea and thirst killed him. CHIEF Yeoman Theodore R. Brownell, Fort Smith, Ark., slender and medium sized, had found a comrade in a long Army beanpole, Pvt. William Earl Surber, Colorado Springs. ''We lay together like a tablespoon and a teaspoon," said Brownell. "But I got the best of it. "He was long enough to keep me warm, but I wasn't long enough to keep him warm at the two ends." THE TWO MEN talked often of the hereafter which they both expected to enter shortly, and repeatedly Surber said, "I'm worried. I want to get baptized." There was no chaplain sane or strong enough to do it. So Brownell baptized him with the only water he had -- saliva. Surber died soon after. Japan Sighted At Long Last The men saw and smelled Japan Jan. 30. Finally they were in the harbor of Moji in northern Kyushu. The neat little Jap officers came aboard and asked for the senior officer. Said one officer: "When Lt. Col. Beecher walked out, his shirt clotted with filth, a dirty towel wound around his brow, his beard and hair hanging down, and gave them a feeble sort of salute, he leaned back against the bulkhead as though just doing that had exhausted him. "There were slop buckets on one side of him and the morning's dead piled on the other. "You could see that the Moji officials were taken aback." THE TEMPERATURE was above freezing. The Japs lined the prisoners up on the deck, ordered them to strip and sprayed them with disinfectant. Meanwhile the Jap doctors discovered the dysentery. The men were tested with long glass rods inserted in the body -- even the dead were tested, through some Jap quirk. A little clothing was distributed and the last muster aboard the ship called. It showed 435 men still alive (a few survivors say 425) out of some 1,600. Many were beyond recall. Men March To Auditorium The Japs marched the men to an auditorium where they were seated on the floor and ordered to remove their shoes. Few obeyed; they were beyond caring. They were given rice, then volunteers were mustered to carry the extremely ill to the hospital. The party began to break up. In the various camps to which they were taken, about 131 soon died. A CAVITE naval officer, Lt. Edward Little, Decatur, Ill., seeing the thin line of survivors from the cruise march into one camp, asked how many had died. "If you want to see dead men," he was told, "there they stand before you." An officer who survived, telling his story to an American rescue party after Japan surrendered, listened in silence as his hearers said what they thought of the Japs. When they had finished, he said, "Yes, the Japs are as bad as you say. But we, the 300 or so living, we are devils, too. "If we had not been devils, we could not have survived. When you speak of the good and the heroic, don't talk about us. "The generous men, the unselfish men, are the men we left behind." (The end.) |

FURTHER INFO:

Trial of Toshino - USA v. Junsaburo Toshino et al (11MB PDF)

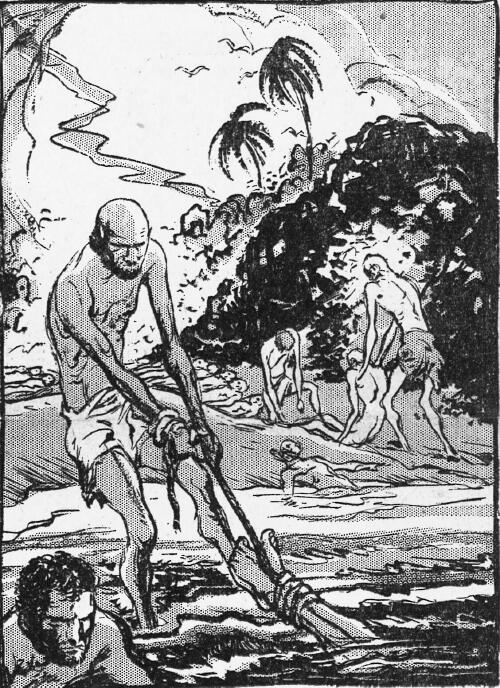

Details on Oryoku Maru (POW Research Network Japan) (external site)