From the early 1940's, a good number of books came out containing information regarding harsh treatment under the Japanese forces, most written by civilian internees who had been repatriated on the exchange ships:

Hill, Max, Exchange

Ship (New York, 1942)

Marsman, Jan Henrik, I Escaped from Hong Kong (New York, 1942)

Brown, H. J., In Japanese Hands (North Newton, KS, 1943)

Brown, Wenzell, Hong Kong Aftermath (New York, 1943)

Dew, Gwen, Prisoner of the Japs (New York, 1943)

Hammond, Helen E., and Robert Bruce, Bondservants (Pasadena, CA, 1943)

Heaslett, Samuel, From a Japanese Prison Camp (London, 1943)

Long, Frances, Half A World Away (New York, 1943)

Marquardt, Frederic S., Before Bataan - And After (Indianapolis, 1943)

McLaren, Chas. L., Eleven Weeks in a Japanese Police Cell (Melbourne, 1943)

Morrison, Ian, Malayan Postscript (Sydney, 1943)

Osborn, L. C., From the Mouth of the Lion (Cleveland, 1943)

Proulx, Benjamin A., Underground from Hong Kong (New York, 1943)

Tolischus, Otto D., Tokyo Record (New York, 1943)

Van der Grift, Cornelis and E. H. Lansing, Escape from Java (New York, 1943)

Brines, Russell, ...Until They Eat Stones (New York, 1944)

Droste, Ch. B., Till Better Days (Melbourne, 1944)

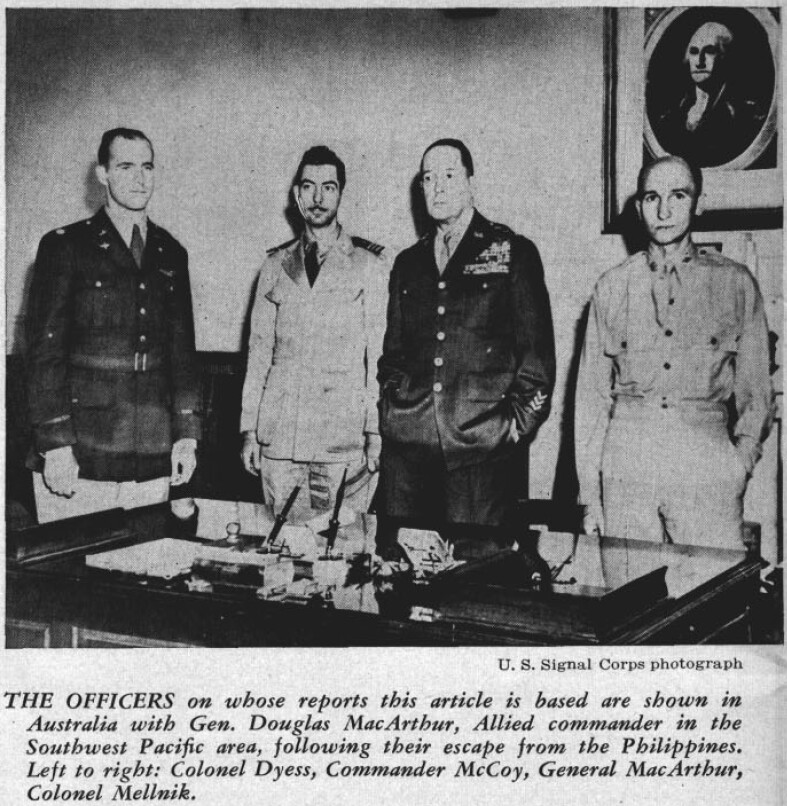

McCoy, Melvyn H. and S.M. Mellnik, Ten Escape from Tojo (New York, 1944)

Priestwood, Gwen, Through Japanese Barbed Wire (London, 1944)

Turner, W. H., I Was a Prisoner of the Japanese (Franklin Springs, GA, 1944)

Marsman, Jan Henrik, I Escaped from Hong Kong (New York, 1942)

Brown, H. J., In Japanese Hands (North Newton, KS, 1943)

Brown, Wenzell, Hong Kong Aftermath (New York, 1943)

Dew, Gwen, Prisoner of the Japs (New York, 1943)

Hammond, Helen E., and Robert Bruce, Bondservants (Pasadena, CA, 1943)

Heaslett, Samuel, From a Japanese Prison Camp (London, 1943)

Long, Frances, Half A World Away (New York, 1943)

Marquardt, Frederic S., Before Bataan - And After (Indianapolis, 1943)

McLaren, Chas. L., Eleven Weeks in a Japanese Police Cell (Melbourne, 1943)

Morrison, Ian, Malayan Postscript (Sydney, 1943)

Osborn, L. C., From the Mouth of the Lion (Cleveland, 1943)

Proulx, Benjamin A., Underground from Hong Kong (New York, 1943)

Tolischus, Otto D., Tokyo Record (New York, 1943)

Van der Grift, Cornelis and E. H. Lansing, Escape from Java (New York, 1943)

Brines, Russell, ...Until They Eat Stones (New York, 1944)

Droste, Ch. B., Till Better Days (Melbourne, 1944)

McCoy, Melvyn H. and S.M. Mellnik, Ten Escape from Tojo (New York, 1944)

Priestwood, Gwen, Through Japanese Barbed Wire (London, 1944)

Turner, W. H., I Was a Prisoner of the Japanese (Franklin Springs, GA, 1944)

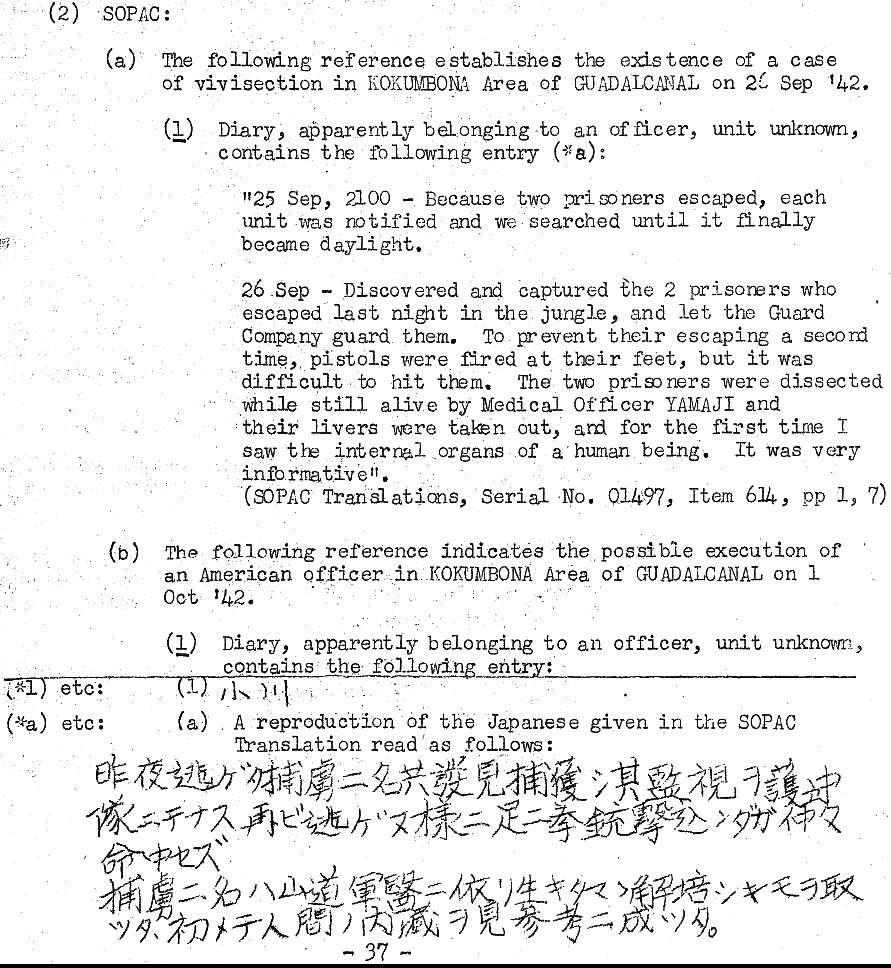

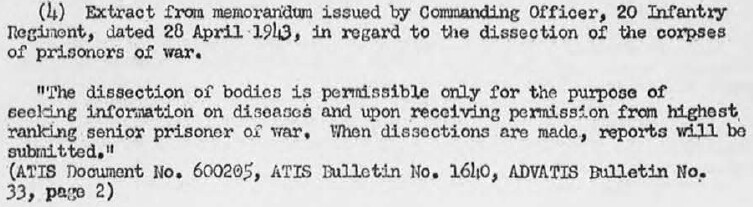

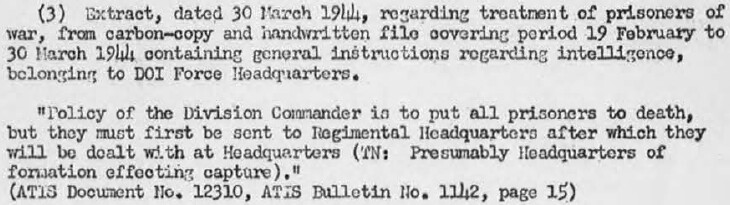

Perhaps the earliest our military leaders learned about the numerous Japanese atrocities was through the secret Allied Translator and Interpreter Service (ATIS) information bulletins which contained excerpts of interviews with Japanese POW's revealing accounts of atrocities committed against Allied soldiers and civilians. One can only imagine the horror and intense anger the general public would have had were these reports widely disseminated in 1942.

Initial Reports of Atrocities

|

THE DEPARTMENT OF STATE BULLETIN

VOLUME VIII: Numbers 184-209 January 2 - June 26, 1943 APRIL 24, 1943 JAPANESE TRIAL AND EXECUTION OF

AMERICAN AVIATORS

Statement by the President [Released to the press by the White House April 21] It is with a feeling of deepest horror, which I know will be shared by all civilized peoples, that I have to announce the barbarous execution by the Japanese Government of some of the members of this country's armed forces who fell into Japanese hands as an incident of warfare. The press has just carried the details of the American bombing of Japan a year ago. The crews of two of the American bombers were captured by the Japanese. On October 19, 1942 this Government learned from Japanese radio broadcasts of the capture, trial, and severe punishment of those Americans. Continued endeavor was made to obtain confirmation of those reports from Tokyo. It was not until March 12, 1943 that the American Government received the communication given by the Japanese Government stating that these Americans had in fact been tried and that the death penalty had been pronounced against them. It was further stated that the death penalty was commuted for some but that the sentence of death had been applied to others. This Government has vigorously condemned this act of barbarity in a formal communication sent to the Japanese Government. In that communication this Government has informed the Japanese Government that the American Government will hold personally and officially responsible for these diabolical crimes all of those officers of the Japanese Government who have participated therein and will in due course bring those officers to justice. This recourse by our enemies to frightfulness is barbarous. The effort of the Japanese warlords thus to intimidate us will utterly fail. It will make the American people more determined than ever to blot out the shameless militarism of Japan. I have instructed the Department of State to make public the text of our communication to the Japanese Government. United States Communication of

April 12, 1943

to the Japanese Government [Released to the press April 21] The Government of the United States has received the reply of the Japanese Government conveyed under date of February 17, 1943, to the Swiss Minister at Tokyo to the inquiry made by the Minister on behalf of the Government of the United States concerning the correctness of reports broadcast by Japanese radio stations that the Japanese authorities intended to try before military tribunals American prisoners of war, for military operations, and to impose upon them severe penalties including even the death penalty. The Japanese Government states that it has tried the members of the crews of American planes who fell into Japanese hands after the raid on Japan on April 18 last, that they were sentenced to death and that, following commutation of the sentence for the larger number of them, the sentence of death was applied to certain of the accused. The Government of the United States has subsequently been informed of the refusal of the Japanese Government to treat the remaining American aviators as prisoners of war, to divulge their names, to state the sentences imposed upon them or to permit visits to them by the Swiss Minister as representative of the protecting Power for American interests. The Japanese Government alleges that it has subjected the American aviators to this treatment because they intentionally bombed nonmilitary installations and deliberately fired on civilians, and that the aviators admitted these acts. The Government of the United States informs the Japanese Government that instructions to American armed forces have always ordered those forces to direct their attacks upon military objectives. The American forces participating in the attack on Japan had such instructions and it is known that they did not deviate therefrom. The Government of the United States brands as false the charge that American aviators intentionally have attacked non-combatants anywhere. With regard to the allegation of the Japanese Government that the American aviators admitted the acts of which the Japanese Government accuses them, there are numerous known instances in which Japanese official agencies have employed brutal and bestial methods in extorting alleged confessions from persons in their power. It is customary for those agencies to use statements obtained under torture, or alleged statements, in proceedings against the victims. If the admissions alleged by the Japanese Government to have been made by the American aviators were in fact made, they could only have been extorted fabrications. Moreover, the Japanese Government entered into a solemn obligation by agreement with the Government of the United States to observe the terms of the Geneva Prisoners of War Convention. Article 1 of that Convention provides for treatment as prisoners of war of members of armies and of persons captured in the course of military operations at sea or in the air. Article 60 provides that upon the opening of a judicial proceeding directed against a prisoner of war, the representative of the protecting Power shall be given notice thereof at least three weeks prior to the trial and of the names and charges against the prisoners who are to be tried. Article 61 provides that no prisoner may be obliged to admit himself guilty of the act of which he is accused. Article 62 provides that the accused shall have the assistance of qualified counsel of his choice and that a representative of the protecting Power shall be permitted to attend the trial. Article 65 provides that sentence pronounced against the prisoners shall be communicated to the protecting Power immediately. Article 66 provides, in the event that the death penalty is pronounced, that the details as to the nature and circumstances of the offense shall be communicated to the protecting Power, for transmission to the Power in whose forces the prisoner served, and that the sentence shall not be executed before the expiration of a period of at least three months after such communication. The Japanese Government has not complied with any of these provisions of the Convention in its treatment of the captured American aviators. The Government of the United States calls again upon the Japanese Government to carry cut its agreement to observe the provisions of the Convention by communicating to the Swiss Minister at Tokyo the charges and sentences imposed upon the American aviators, by permitting the Swiss representatives to visit those now held in prison, by restoring to those aviators the full rights to which they are entitled under the Prisoners of War Convention, and by informing the Minister of the names and disposition or place of burial of the bodies of any of the aviators against whom sentence of death has been carried out. If, as would appear from its communication under reference, the Japanese Government has descended to such acts of barbarity and manifestations of depravity as to murder in cold blood uniformed members of the American armed forces made prisoners as an incident of warfare, the American Government will hold personally and officially responsible for those deliberate crimes all of those officers of the Japanese Government who have participated in their commitment and will in due course bring those officers to justice. The American Government also solemnly warns the Japanese Government that for any other violations of its undertakings as regards American prisoners of war or for any other acts of criminal barbarity inflicted upon American prisoners in violation of the rules of warfare accepted and practiced by civilized nations as military operations now in progress draw to their inexorable and inevitable conclusion, the American Government will visit upon the officers of the Japanese Government responsible for such uncivilized and inhumane acts the punishment they deserve. |

Events Leading Up to

WWII 1931-1944.doc

April 21, 1943. Announcement of the execution by the Japanese of American prisoners of war. [Statement of President Roosevelt.]

"This Government has vigorously condemned this act of barbarity in a formal communication sent to the Japanese Government. In that communication this Government has informed the Japanese Government that the American Government will hold personally and officially responsible for these diabolical crimes all of those officers of the Japanese Government who have participated therein and will in due course bring those officers to justice." (Bulletin, Vol. VIII, No. 200, p. 337.)

January 31,1944. Combined United States forces invaded Kwajalein.

The United States Department of State issued a statement in which it revealed a series of protests and requests concerning the treatment of prisoners made by the United States to Japan from December 7, 1941, to date.

MAGIC Vol. IV

510. Japanese Apprehend Blue Shirt Terrorists

On November 21 [1941] Shanghai officials declared that the Blue Shirts' activities in Shanghai and Nanking had been completely stopped, but that Generalissimo Chiang Kai‑shek was still attempting to promote underground movements in those areas. Apparently political prisoners captured in northern China were to be sent to Nagasaki; for the following day Tokyo requested information concerning the method, channels, means of transportation and time required for shipping the prisoners.

April 21, 1943. Announcement of the execution by the Japanese of American prisoners of war. [Statement of President Roosevelt.]

"This Government has vigorously condemned this act of barbarity in a formal communication sent to the Japanese Government. In that communication this Government has informed the Japanese Government that the American Government will hold personally and officially responsible for these diabolical crimes all of those officers of the Japanese Government who have participated therein and will in due course bring those officers to justice." (Bulletin, Vol. VIII, No. 200, p. 337.)

January 31,1944. Combined United States forces invaded Kwajalein.

The United States Department of State issued a statement in which it revealed a series of protests and requests concerning the treatment of prisoners made by the United States to Japan from December 7, 1941, to date.

MAGIC Vol. IV

510. Japanese Apprehend Blue Shirt Terrorists

On November 21 [1941] Shanghai officials declared that the Blue Shirts' activities in Shanghai and Nanking had been completely stopped, but that Generalissimo Chiang Kai‑shek was still attempting to promote underground movements in those areas. Apparently political prisoners captured in northern China were to be sent to Nagasaki; for the following day Tokyo requested information concerning the method, channels, means of transportation and time required for shipping the prisoners.

Initial Military Reports and News Articles

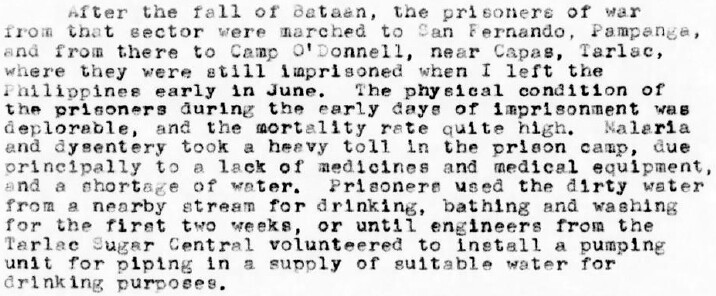

Parsons_Report_on_Japanese_Occupation_of_Philippine Islands_1942-08-12

by Charles "Chick" Parsons, Jr.; written aboard the MS Gripsholm; one of the very first to

mention Bataan march. (PDF)We Escape, Sunday Times (Perth), Dec. 27, 1942 (PDF, courtesy of Fred Baldassarre) - Story of Army Captains William Osborne and Damon Gause and their escape from the Philippines to Australia; mention of Bataan and Manila marches on pages 3 and 4.

Escape_of_Lt_Cmdr_Melvyn_McCoy_from_Japanese_Prison_Camp_c_AUG_1943 (PDF)

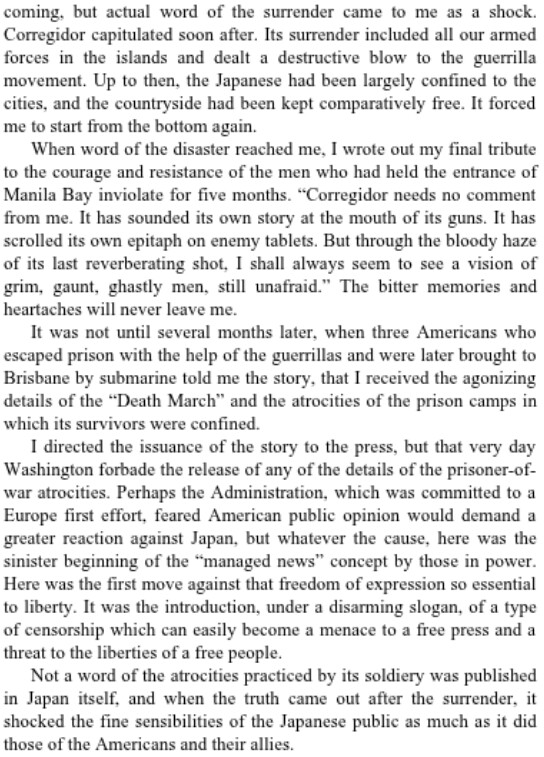

Ten Escape From Tojo by Cmdr. McCoy and Lt. Col. Mellnik - original written cir. Sept. 1943; published in book form, March 1944.

The Dyess Story: The Eye-Witness Account of the Death March from Bataan and the Narrative of Experiences in Japanese Prison Camps and of Eventual Escape - written in Sept. 1943 and published in 1944.

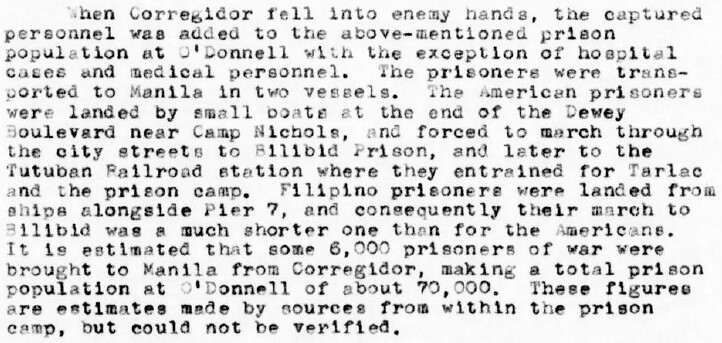

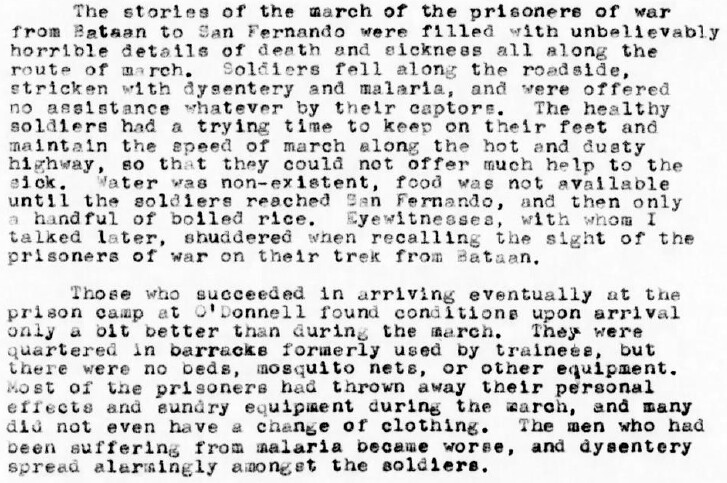

Excerpts from Parsons Report:

(NOTE: POWs from Corregidor were marched through Manila and then taken to Bilibid Prison, and then on to Cabanatuan, not to Camp O'Donnell. POWs from O'Donnell later joined the Corregidor POWs. See Provost Marshal General Report on American Prisoners of War in the Philippines and Medical Report by Wibb Cooper.)

US Govt. regarding keeping a lid on the news about atrocities

(Transcriptions

courtesy of Scott Proudfit)

|

SECRET

THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON September 9,

1943

S E C R E T MEMORANDUM FOR: The Secretary of War. The Secretary of the Navy. Subject: Japanese Atrocities – Reports of by Escaped Prisoners. 1. I agree with your opinion that any publication of Japanese atrocities at this time might complicate the present and future missions of the GRIPSHOLM and increase the mistreatment of prisoners now in Japanese hands. I request, therefore, that you take effective measures to prevent the publication or circulation of any stories emanating from escaped prisoners until I have authorized a release. 2. It might be well for the Joint Chiefs of Staff to make recommendation as to the moment when I should inform the country of the mistreatment of our nationals. s/FRANKLIN D.

ROOSEVELT

Copy to: Admiral Leahy SECRET

|

| TO: CINC SWPA FROM: WASHINGTON NR: 8843 7TH OCT 43 The President has directed that measures should be taken to prevent the publication and circulation of atrocity stories (for MacArthur, Harmon, Richardson, Emmons, Buckner and Stilwell) emanating from escaped prisoners until he has authorized the release. One reason for this decision was not to jeopardize the present and future mission of the exchange ship Gripsholm particularly the delivery of food and medical supplies carried on that exchange ship. It is desired that effective measures be taken to prevent the circulation or publication of such stories emanating from any source. COMINCH has requested that this information be passed to naval commanders in your areas. Source:

MACARTHUR ARCHIVES

|

| TO: CINC SWPA (MACARTHUR) FROM: WASHINGTON NR: 9129 THIRTEENTH OCT 43 The President has directed that publication of stories of Japanese atrocities will be withheld until he has authorized their release and has asked that the Joint Chiefs of Staff advise him as to the moment when he should advise the country of the mistreatment of our nationals. In considering the President’s request, (Reference our 8843 of 6 October and your C-6490 of 8 October) the Joint Chiefs of Staff recommend to him that, for the time being, the release of this information be withheld and advised him that they would make recommendations later regarding the publication of such information when it is felt that the opportune time has arrived. There is deep concern here regarding the atrocities committed by the Japanese against our nationals and also Japans failure to supply necessary food, shelter, clothing and medical supplies. Studies are now being conducted to determine the most appropriate course to secure better treatment for American prisoners held by the Japanese. There is grave doubt as to whether this can be accomplished through the pressure of world public opinion brought about by the publication of the atrocity stories. The possibility of violent adverse reaction by the Japanese to such publication cannot be overlooked. Your common interest with the Australian Government in this matter is recognized. The British and the Chinese likewise have an interest and it is my intention to propose that the Combined Chiefs of Staff reach an agreement as to the course to be followed. This proposal will include a recommendation that the British Chiefs of Staff ascertain the views of the British Commonwealth Governments and also seek their cooperation in the controlling release of atrocity stories until a uniform policy has been worked out. Meanwhile, it is desired that you also use your best efforts to secure the cooperation of the Australian Government in preventing the circulation of publication of Japanese atrocity stories until there has been combined consideration of the problem and a decision as to a uniform policy to be followed. MARSHALL Source:

MACARTHUR ARCHIVES, Record Group 4: Box 16: Folder 4, "War Dept.

Sept-Dec. 1943"

|

|

SECRET

ALLIED INTELLIGENCE BUREAU. PHILIPPINE REGIONAL SECTION AIB Info. Report No. 1309 Date: 6 Dec 43

Message Reference Sheet

No. 929 TO: Chief of Staff Coordination: G-2 Message No. 45 from ABCEDE Precis: In re enemy terror campaign in NEGROS. Comment: ABCEDE’s position is understandable but it all goes to the question of the United States’ policy. If we will not serve sharp warning of future accountability for the mistreating of American prisoners of war, it is hardly possible that the administration would champion the cause of the Filipino civilian. Of course the whole matter is a delicate one. With so many prisoners in the enemy’s hands it is difficult for us to threaten “reprisals by United Nations.” About all that we could do would be to reaffirm our determination to hold the leaders responsible for atrocities to post war trial and punishment as has already been done in a general way. It occurs to me that the C-in-C might afford the people some little protection against the wanton killing of civilian non-combatants by addressing letters to the several commanders directing that the names of all enemy leaders responsible for atrocities against the civil populace be submitted to him with the accompanying supporting evidence for the post war punishment of the offenders. Such a letter in the hands of commanders, if made public, would demonstrate to the people the C-in-C’s concern for their protection and would serve as a warning to the enemy which he might or might not heed. If this procedure should be viewed favorably, I will submit a tentative draft of such a letter for your further consideration. Action taken: None. Action recommended: None, subject to the above comment. C.W. SECRET

Source: MACARTHUR ARCHIVES, R6-16. Box 64. Folder 1, “P.R.S. Admin. Dec 1943” |

|

SECRET

GENERAL HEADQUARTERS SOUTHWEST PACIFIC AREA CHECK SHEET (Do not remove from attached sheets) File No.: Subject: From: PRS To: C/S Date: 30 Jan 44 1. Opportunity to evaluate reaction in treatment of our Prisoners of War to release of the enemy atrocity disclosures, is only possible through information obtainable from our intelligence contacts in the several areas concerned. 2. Suggest message be dispatched to appropriate contacts as follows: “HAVE AGENTS OBSERVE AND REPORT ON ANY CHANGES IN TREATMENT OF INTERNEES OR PRISONERS OF WAR RESULTING FROM RECENT DISCLOSURE OF ENEMY ATROCITIES COMMITTED ON AMERICAN AND FILIPINO PRISONERS OF WAR CAMPS PD DETERMINE WHETHER AND TO WHAT EXTENT RED CROSS SUPPLIES LANDED IN MANILA ON TEIA MARU ON SIXTH NOVEMBER WERE DISTRIBUTED AMONG INTERNEES AND POW.” C.W. DC/S To: Chief PRS Thru: G-2 30 Jan 44 Approved. RJM. G-2 PRS Noted. 30 Jan 44 C.A.W. SECRET

Source: MACARTHUR ARCHIVES, Record Group 16, Box 64, Folder 2, "P.R.S. Admin. Jan 1944" |

Regulations were already in place for escaped POWs-- see these instructions regarding safeguarding prisoner of war information that all escapees had to sign (from European Theater; not confirmed, but assume the same was distributed in the Pacific Theater):

Safeguarding_of_POW_Info_form_1942-10-19.jpg

Instructions_re_Publicity_Escaped_POWs_form_1943-08-06.jpg

See also this Code of Wartime Practices for American Broadcasters, June 15, 1942, to better understand the importance of safeguarding war-related information.

Instructions_re_Publicity_Escaped_POWs_form_1943-08-06.jpg

See also this Code of Wartime Practices for American Broadcasters, June 15, 1942, to better understand the importance of safeguarding war-related information.

From Secrets of Victory by Sweeney re laying off and downplaying stories about POWs, Feb. 26 and also winter of 1942:

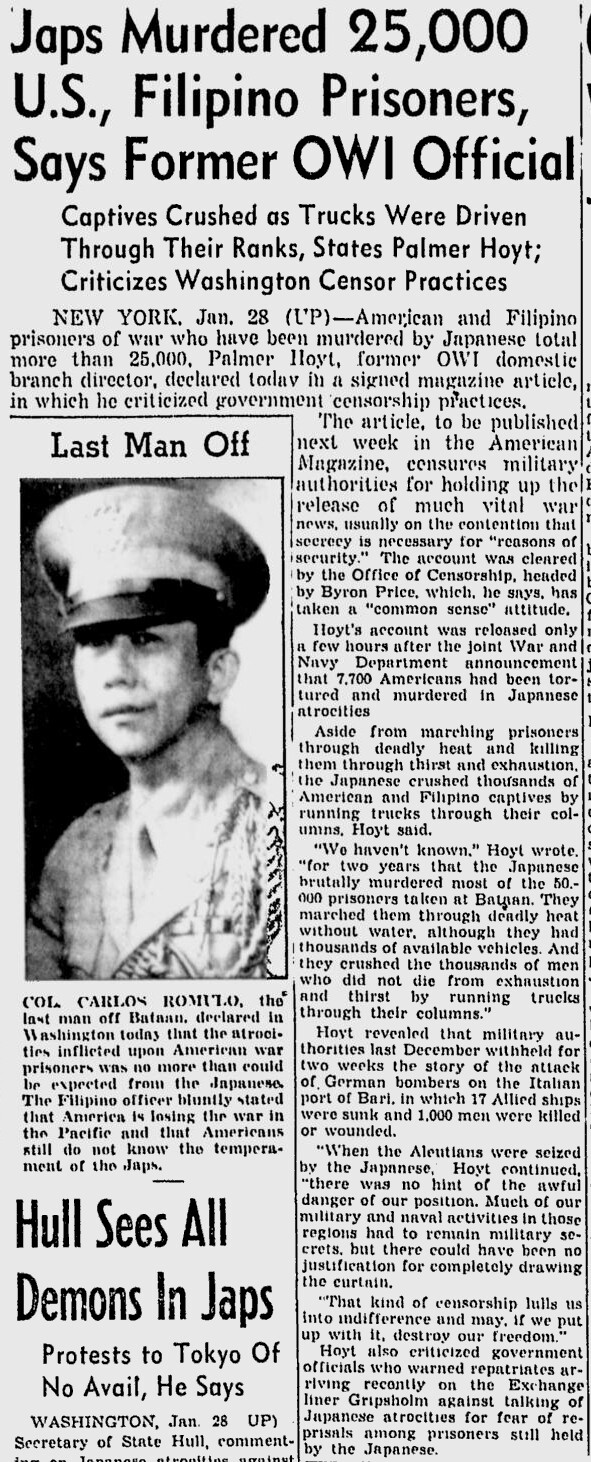

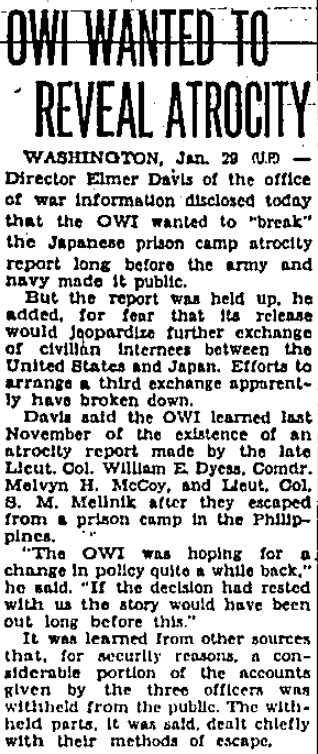

One OWI (Office of War Information) official was critical of the censorship:

From All Hands magazine article, The March of Death, March 1944:

From the Forward to The Dyess Story:

| The story of Dyess and his companions and the

atrocities they had witnessed had been withheld for months by the

government in the fear that its publication would result in death to

thousands of American prisoners still in Japanese hands. When all hope

of aiding the prisoners passed, the story was released. The swift recognition of the Dyess story's importance is due largely to Byron Darnton's dispatch, which might never have been written, except that World War II has been the most fully reported conflict in history. The army of news- paper and magazine correspondents and photographers is the greatest ever assigned to a war. Their intensive coverage of even the most remote sectors on the battlefronts of the world has unearthed and preserved thrilling and historical chapters by the thousands. It was this new standard of war reporting that took Darnton to the isolated Australian hospital where he met Ben Brown. It was a year later, in July, 1943, that a brief telegraphic dispatch chronicled the safety and good health of one Major William Edwin Dyess, of the army air forces, who for many months had been a prisoner of the Imperial Japanese army. In some newspapers the dispatch appeared as written. In many others it did not appear. Certain editors sent the dispatch to their morgues with the scribbled query: "Who is he?" And when the Darnton clipping was laid before them, the Dyess item became big news. .......... Dyess's importance as an American hero -- as established by Darnton's dispatch -- was responsible for a concerted rush to obtain the full story. And when, in the course of their efforts, newspapers and magazine editors learned something of Dyess's appalling experiences in Japanese prison camps, the struggle for the right to publish them grew epochal. By September 5, 1943, when Dyess was recuperating in the army's Ashford General Hospital at White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, the stiffening competition had narrowed the field of bidders to a national weekly magazine and The Chicago Tribune, representing 100 associated newspapers. The Tribune was successful, not because it outbid the magazine, but because it could promise Dyess, now a lieutenant colonel, a daily circulation of ten million and an estimated daily audience of forty million against the magazine's circulation of about three million weekly and estimated reader audience of twelve million. Colonel Dyess's consuming determination to expose to the world Japan's barbaric treatment of American war prisoners decided him in favor of the daily newspapers and their vastly larger audience. The Tribune obtained the War Department's permission for Colonel Dyess to tell his story. Only three days later the Secretary of War withdrew the permission and forbade Dyess to divulge any further details of his prison camp experience or escape from the Japs. The Tribune had the story, but we faced a four-and-a-half-month battle for its release. Official reluctance, indecision, resistance, and actual hostility in high places all contributed to lengthening the fight. In the end, the story came out and was given to the American people by their newspapers. There was good reason in July, 1943, why editors might have been slow to recognize the Dyess epic for what it was. In the first place, Dyess himself was practically unknown. Many editors, as has been seen, lacked the background material that would have established him as a hero of the first rank. At that time, too, the Swedish repatriation liner Gripsholm already had made one trip, returning American civilian internees who had flooded the magazines and newspapers with stories of Jap callousness and neglect. Japanese prison stories were on their way to being old stuff. But to those who read it, the Darnton dispatch carried a mighty message: here was a man who had lived behind the curtain of military secrecy the Japanese had drawn upon Bataan after the surrender and who could tell what actually had happened to the battered remnants of MacArthur's armies after the Stars and Stripes had been hauled down. |

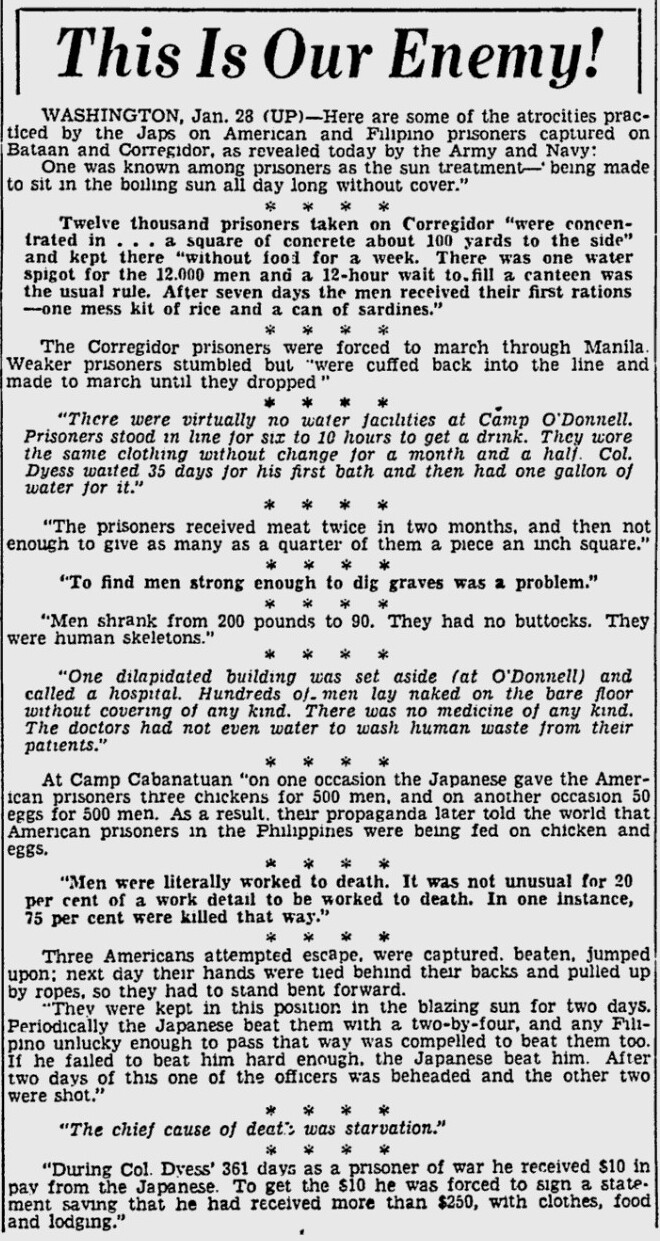

The original story on Japanese atrocities in the Philippines was written in July 1943. The media was given permission to publish in January 1944 -- see Jan. 28, 1944 article, Jap Atrocities Arouse Nation.

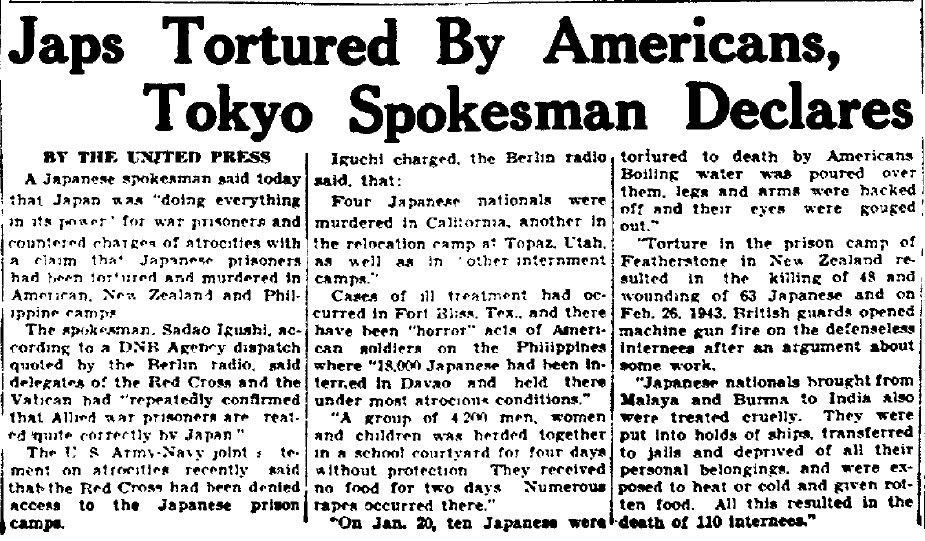

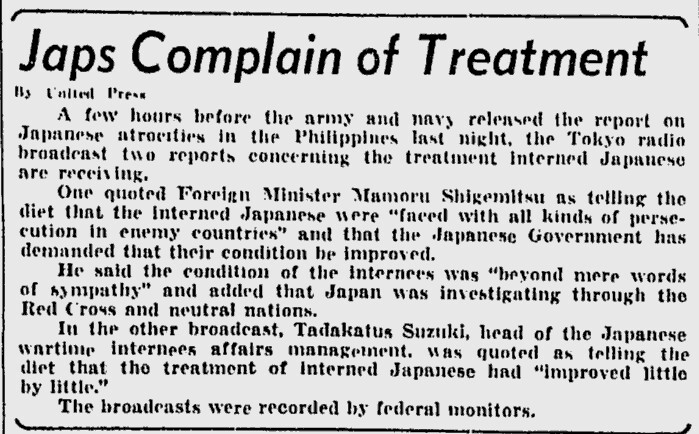

This was not the first time the media published news about atrocities:

Atrocity

Report Prompts Appeal 1942-3-11

Harrop Escapes 1942-3-11

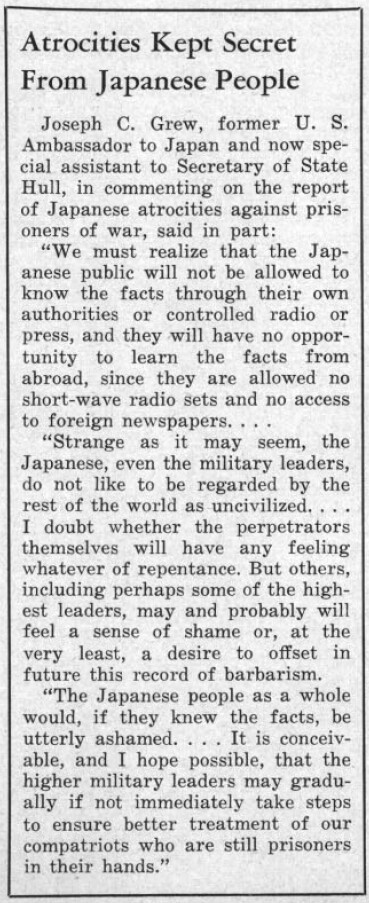

Grew tells of atrocities 1942-8-31

Motives of Japanese Atrocity 1943-4-29 a

Japanese Behead Airman 1943-10-6

Harrop Escapes 1942-3-11

Grew tells of atrocities 1942-8-31

Motives of Japanese Atrocity 1943-4-29 a

Japanese Behead Airman 1943-10-6

Here is a collection of LIFE magazine articles from that early period (PDF files available in File Bin):

LIFE

May 25, 1942 - Letters To The Editors: Prisoners of the Japs

LIFE Sep 7, 1942 - Americans Return from Jap Prison Camps

LIFE Sep 7, 1942 - Yankee Girl: Five Months in Jap Internment Camp at Manila (Frances Long)

LIFE Sep 14, 1942 - Japs Lie About U.S. Heroes

LIFE Sep 21, 1942 - Tokyo in Wartime (Phyllis Argall)

LIFE Dec 7, 1942 - Report from Tokyo: Ambassador Warns of Japan's Strength (Joseph Grew)

LIFE Nov 29, 1943 - Letter from Mormugao (Shelley Mydans)

LIFE Dec 6, 1943 - Twenty-one Months as Prisoners of the Japanese (Carl and Shelley Mydans)

LIFE Dec 20, 1943 - Americans Return: Story of Repatriate Homecoming

LIFE Sep 7, 1942 - Americans Return from Jap Prison Camps

LIFE Sep 7, 1942 - Yankee Girl: Five Months in Jap Internment Camp at Manila (Frances Long)

LIFE Sep 14, 1942 - Japs Lie About U.S. Heroes

LIFE Sep 21, 1942 - Tokyo in Wartime (Phyllis Argall)

LIFE Dec 7, 1942 - Report from Tokyo: Ambassador Warns of Japan's Strength (Joseph Grew)

LIFE Nov 29, 1943 - Letter from Mormugao (Shelley Mydans)

LIFE Dec 6, 1943 - Twenty-one Months as Prisoners of the Japanese (Carl and Shelley Mydans)

LIFE Dec 20, 1943 - Americans Return: Story of Repatriate Homecoming

The Dyess-Mellnik-McCoy story and details regarding the Death March, POW camps and hellship journey were considered by our military leaders too inflammatory to release to the public immediately. When the story did break, the media was quick to publish.

from Pittsburgh Press, Jan. 28, 1944

Another LIFE magazine article: LIFE_Long_delayed_reports_on_Japanese_atrocities_1944-02-28

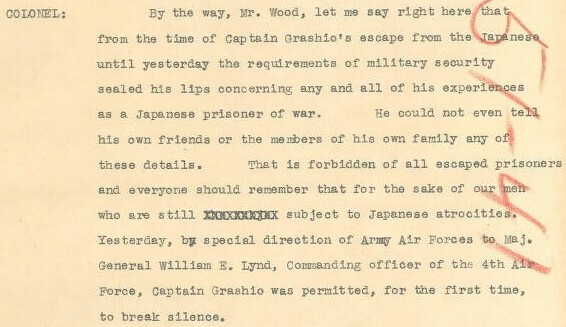

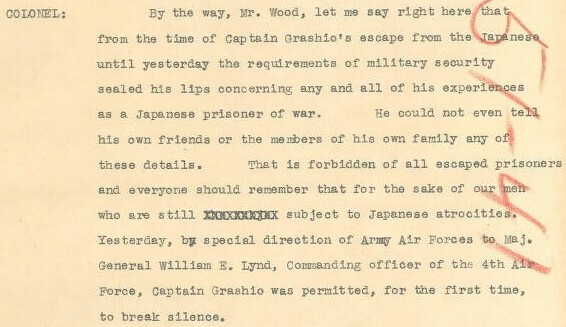

From Fox Movietone News interview of escapee Capt. Samuel Grashio by Col. Ralph Snavely on Jan. 29, 1944 and aired on Feb. 2:

..........

From Fox Movietone News interview of escapee Capt. Samuel Grashio by Col. Ralph Snavely on Jan. 29, 1944 and aired on Feb. 2:

..........

Also from Grashio, noted in Twin Falls Times News, January 30, 1944: Officer Saw 1,100 Americans, 14,000 Filipino Captives Die. From the same paper, on page 6:

LIFE Feb 7, 1944 - Prisoners of Japan: Ten Americans Report on Atrocities (Mellnik, McCoy, Dyess and others)

LIFE Feb 28, 1944 - LIFE's Report ("The long-delayed reports on Japanese atrocities against U.S. prisoners in the Philippines were the sensation of the month."

Article from the Toledo Blade, Jan. 28, 1944: Congressmen_Denounce_Jap_Atrocity

The Australian press published the news widely:

Mellnick-McCoy-Dyess

Story - West Australian 1944-01-29.pdf

Hang the Mikado - Sunday Times, Perth 1944-01-30.pdf

War Prisoners Worked to Death in Jap Camp - Canberra Times 1944-01-31.pdf

Allied Nations Shocked by Atrocities - Advocate 1944-01-31.pdf

Inhuman Treatment of Prisoners by Japs - Townsville Daily 1944-01-31.pdf

Japanese Brutality to War Prisoners - Morning Bulletin 1944-01-31.pdf

More Tales of Japanese Savagery - Courier-Mail 1944-01-31.pdf

Hang the Mikado - Sunday Times, Perth 1944-01-30.pdf

War Prisoners Worked to Death in Jap Camp - Canberra Times 1944-01-31.pdf

Allied Nations Shocked by Atrocities - Advocate 1944-01-31.pdf

Inhuman Treatment of Prisoners by Japs - Townsville Daily 1944-01-31.pdf

Japanese Brutality to War Prisoners - Morning Bulletin 1944-01-31.pdf

More Tales of Japanese Savagery - Courier-Mail 1944-01-31.pdf

From Tokyo War Crimes trials re broadcasts about atrocities against POWs:

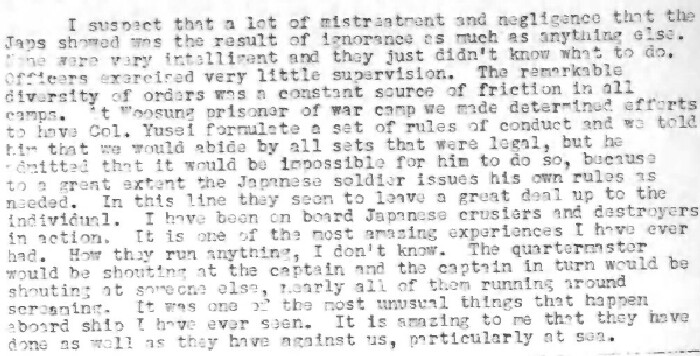

Statement of Cmdr. C. D. Smith (USS Wake), Feb. 26, 1945 - Smith was captured on Dec. 8, 1941. Here are some excerpts from his statement given at the Tokyo War Crimes Trials (statement contains information on the following locations where POWs were held: The Old Chinese Mint; Japanese Naval Prison, Kiangwan Road; Woosung POW Camp; Woosung Gendarmerie; Bridge House; Japanese Army Prison, Kiangwan; Ward Road Jail; Columbia Country Club):

"It would be way better for everyone if the Japanese Navy had charge of

prisoners. The Japanese naval officer approximates a gentleman compared

with the army officer. Most all naval officers speak some English; this

is rare in the army.

"You would be surprised how many Japanese try to be friendly, especially during the last six months of my imprisonment. I have casually suggested to a few officials that torturing was inhuman, but they seem to be mildly surprised that I should assume such an attitude. I am sure that many of them are against torture in principle, but they dare not criticize their superiors."

.....

"The Japanese navy did not take any of my belongings. They did take the belongings of the crew, but they took absolutely nothing of mine. When the army took us over, they took everything."

.....

"At the time we were imprisoned here [Ward Road Jail] there were 9300 prisoners in the institution, making this the world's largest jail."

"You would be surprised how many Japanese try to be friendly, especially during the last six months of my imprisonment. I have casually suggested to a few officials that torturing was inhuman, but they seem to be mildly surprised that I should assume such an attitude. I am sure that many of them are against torture in principle, but they dare not criticize their superiors."

.....

"The Japanese navy did not take any of my belongings. They did take the belongings of the crew, but they took absolutely nothing of mine. When the army took us over, they took everything."

.....

"At the time we were imprisoned here [Ward Road Jail] there were 9300 prisoners in the institution, making this the world's largest jail."

Dept. of State re release of POW information, Sept. 4, 1945 (page 1 only; RG 24 Box 1) - reasons why it was not possible to release information about POW atrocities, mainly that Japan would construe the accounts as "atrocity campaigns," thus making conditions unfavorable for concluding negotiations for the shipment of relief supplies or arrangements for the repatriation of Americans. This document was found with other atrocity-related documents (beheading of airmen in Celebes, Philippines, Chichijima): Record Group 24 Box 1 folders 1-9 initial pages only.

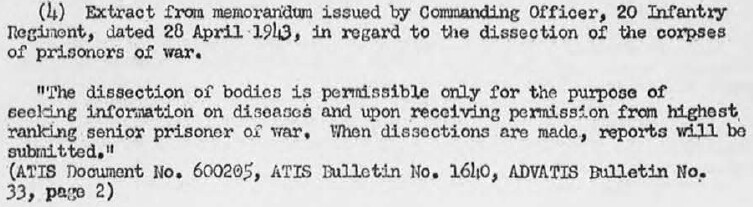

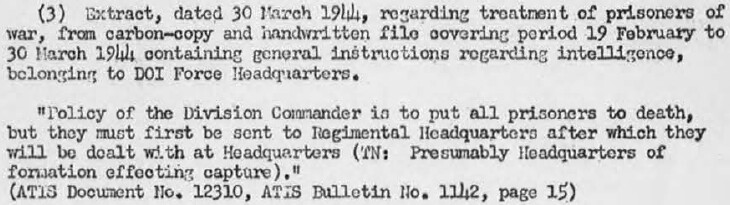

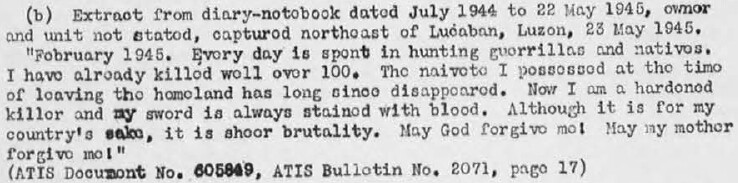

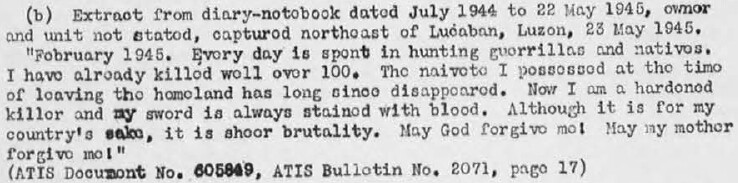

Also kept from the American public were these ATIS bulletins, reports from the battlefield containing translations of interrogations of captured Japanese and excerpts from confiscated documents (Bodine_Diary_Exhibits_re_killing_POWs_civilians.pdf):

"Since they seemed to be good

natives, it was rather difficult to bayonet them to death. The voices

of the women and children crying and wailing were terrifying."

"At first I had kind of a funny feeling but after killing one I found myself accustomed to it."

"It was hard for me to kill them because they seem to be good people. Frightful cries of the children were horrible."

"Japan [is] a selfish nation and the young soldiers, especially those in lower ranks, [are] of barbarous nature."

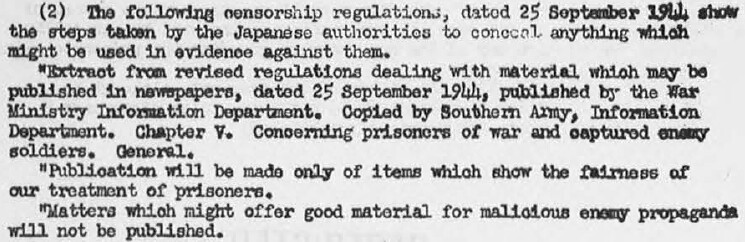

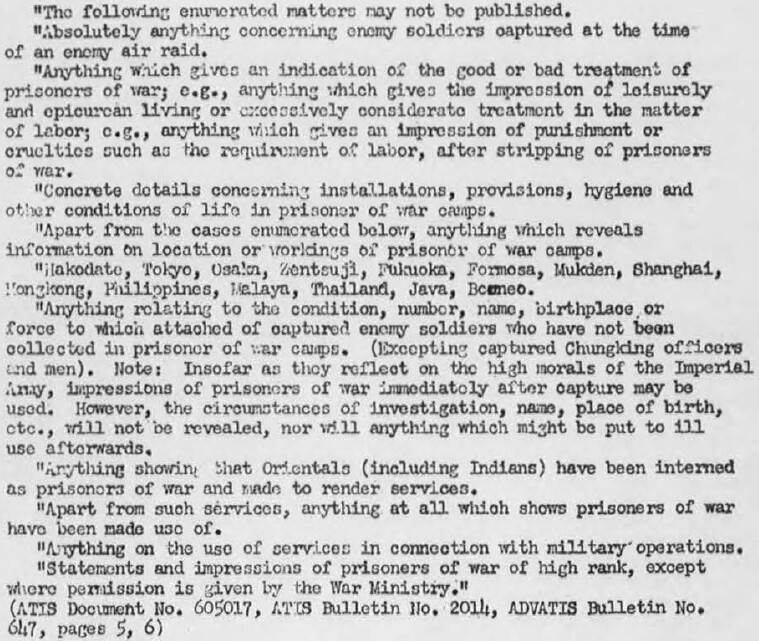

From Japanese censorship regulations, Sept. 25, 1944:

"Chapter V. Concerning prisoners of war and captured enemy soldiers. General. Publication will be made only of items which show the fairness of our treatment of prisoners. Matters which might offer good material for malicious enemy propaganda will not be published."

"At first I had kind of a funny feeling but after killing one I found myself accustomed to it."

"It was hard for me to kill them because they seem to be good people. Frightful cries of the children were horrible."

"Japan [is] a selfish nation and the young soldiers, especially those in lower ranks, [are] of barbarous nature."

From Japanese censorship regulations, Sept. 25, 1944:

"Chapter V. Concerning prisoners of war and captured enemy soldiers. General. Publication will be made only of items which show the fairness of our treatment of prisoners. Matters which might offer good material for malicious enemy propaganda will not be published."

INTERROGATION WITH TORTURE

If the prisoner persists in his obduracy, threats of grave physical discomforts should be made. With utter disregard for the prohibition of brutality, it is proposed, euphemistically to be sure, that "skillful methods" be applied. "Skillful methods" are not defined, but torture is succinctly described. In quaint Japanese circumlocution, brutal directives are disguised in the form of apparently factual statements.

a. Extract from captured booklet entitled "Instructions on How to Interrogate" published in Daily Intelligence Extracts, Hq. 10 Air Force, 18 August (year not given).

"Measures to be normally

adopted... Torture (GOMON) embraces, beating, kicking, and all conduct

involving physical suffering. It is the most clumsy method and only to

be used when all else fails. (Specially marked in text.) When violent

torture is used, change interrogation officer, and it is beneficial if

a new officer questions in sympathetic fashion.

"Threats. As a hint of physical discomforts to come, e.g. murder, torture, starving, deprivation of sleep, solitary confinement, etc. Mental discomforts to come, e.g., will not receive same treatment as other prisoners of war; in event of exchange of prisoners he will be kept till last; he will be forbidden to send letters; will be forbidden to inform his home he is a prisoner of war, etc." (ATIS Research Report No. 86 (Suppl. No. I), page 3).

"Threats. As a hint of physical discomforts to come, e.g. murder, torture, starving, deprivation of sleep, solitary confinement, etc. Mental discomforts to come, e.g., will not receive same treatment as other prisoners of war; in event of exchange of prisoners he will be kept till last; he will be forbidden to send letters; will be forbidden to inform his home he is a prisoner of war, etc." (ATIS Research Report No. 86 (Suppl. No. I), page 3).

b. Extract from handwritten notebook titled "R1 (sic) Service M" concerning intelligence and fifth column operations in total war (undated, writer and unit not stated).

"During the questioning, if the

PW complains repeatedly that he is thirsty and demands water, this is a

sign that he is in agony such as one experiences just before confessing

matters of a vital nature.

"Interrogation should preferably be conducted in such a manner that the PW is led on to talk. However, when the situation demands speed, methods in which pain is inflicted on the PW may be used as well. In either case, consideration must be given to future use and influences." (ATIS Enemy Publication No. 271, page 26).

"Interrogation should preferably be conducted in such a manner that the PW is led on to talk. However, when the situation demands speed, methods in which pain is inflicted on the PW may be used as well. In either case, consideration must be given to future use and influences." (ATIS Enemy Publication No. 271, page 26).

Japanese sources afford too few instances of the actual application of their interrogatory technique, but those that are available require no footnotes. In a Japanese diary captured at KWAJALEIN, the diarist describes all interrogation of three American air PsW, climaxed by a beating administered to an officer who would not "reply as asked" until "that damned officer finally let out a scream." (JICPOA Translation, Item No. 6437 (date unknown), page 3).

c. Extract from statement of Prisoner of War (JA (USA) 100060,) captured at KORAKO, 22 April 1944.

"At KORAKO, about 20 March 1944,

PW saw a US airman tied to a tree and questioned by Lt. SETO (since

killed). Answers were unsatisfactory. Japs in area lined up and beat

Allied PW with clubs. He was revived after becoming unconscious and was

again beaten. Following day a Japanese WO, nicknamed SAMPANG (crooked

legs) by Javanese, made three attempts to behead Allied I'W. Head did

not come off. Another Japanese named INOUYE cut off the head after

third attempt. Several Javanese witnessed the deed." (ATIS

Interrogation Report No. 416, Serial No. 667, page 4).

d. Extract from statement of Dr. I. G. BRAUN, Mission Hospital at AMELE, near MADANG, NEW GUINEA.

"One officer said that the policy

was to tie up the captured airmen, question them pleasantly until they

would give no further information, and then require them to kneel with

a broomstick inside the knee-joints. He stated that after one or two

hours of this 'most of them would talk.' After the second interrogation

was finished, they would be beaten and executed, usually by

decapitation." (Report of AC of S, G-2, ALAMO Force, dated 8 May 1944).

Particularly revolting tortures to extract information are described as follows:

e. Extract from COIS Eastern Fleet, Abstract of Enemy Information No. 6 (dated 8 August 1944).

"The victim's stomach is filled

with water from a hose placed in the throat. A plank is then placed

across the distended stomach, and Japanese, one on each end, then

'see-saw' thus forcing out the water from the stomach. Many of the

victims die under this torture.

"The victim's thumbs are tied together and he is hitched by them to a motor car which proceeds to pull him around in a circle unti1 he falls exhausted. This is repeated at two- or three-day intervals.

''When KEMPEI officers become physically tired from the beating-up of a victim, a second victim is brought in. Each victim is given a stick and they are set to belaboring each other." (ATIS Research Report No. 72 (Suppl. No. 11, page 23).

"The victim's thumbs are tied together and he is hitched by them to a motor car which proceeds to pull him around in a circle unti1 he falls exhausted. This is repeated at two- or three-day intervals.

''When KEMPEI officers become physically tired from the beating-up of a victim, a second victim is brought in. Each victim is given a stick and they are set to belaboring each other." (ATIS Research Report No. 72 (Suppl. No. 11, page 23).

f. Cruel treatment of PsW of all branches of our service has been thoroughly proven in our War Criminal Trials. However, there is some indication that harsh and brutal treatment was applied more to air than to ground troops. In addition, to the statement of Dr. I. G. Braun cited above, there is other evidence that airmen were singled out for harsher treatment. Hiroshi FUJII, formerly a doctor at the OMORI PW Camp, stated at an interview in Sugamo Prison that:

"...in contravention of an order

issued verbally by Col. SAKABA, the Camp Commandant, that Special POW

B-29 air crews were not to receive medical statement, he secretly

performed an operation on a Special POW for hemorrhoids...

"Special POWs, B-29 crew members, received only half rations or two-thirds rations on orders of Col. SAKABA...

"...When he requested the Colonel to allow him to fill out death certificate (for a Special PW), this was refused by SAKABA on the grounds that special prisoners need not be treated the same as other POWs." (Report No. 489 of Investigation Division, Legal Section, GHQ, SCAP).

"Special POWs, B-29 crew members, received only half rations or two-thirds rations on orders of Col. SAKABA...

"...When he requested the Colonel to allow him to fill out death certificate (for a Special PW), this was refused by SAKABA on the grounds that special prisoners need not be treated the same as other POWs." (Report No. 489 of Investigation Division, Legal Section, GHQ, SCAP).

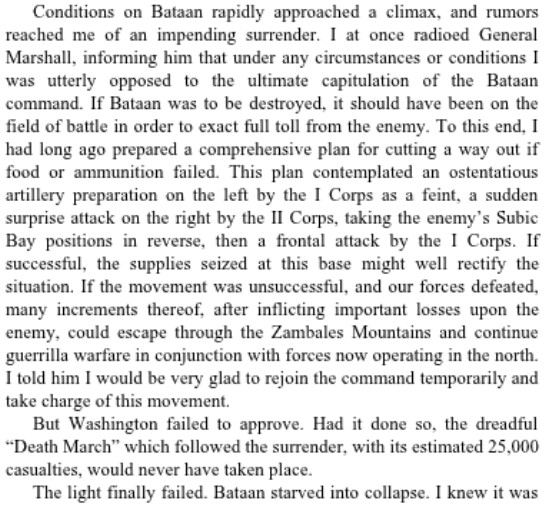

From Gen. Douglas MacArthur's Reminiscences (1964):

"I was deeply

concerned about the thousands of prisoners who had been interned at the

various camps on Luzon since the early days of the war... I had been

receiving reports from my various underground sources long before the

actual landings on Luzon, but the latest information was most alarming.

With every step that our soldiers took toward Santo Tomas University,

Bilibid, Cabanatuan and Los Banos, where these prisoners were held, the

Japanese soldiers guarding them had become more and more sadistic. I

knew that many of these half-starved and ill-treated people would die

unless we rescued them promptly."

From pages 146-147:

From pages 146-147:

For more details on these men and their amazing "Great Escape" from the Davao Penal Colony, read Escape From Davao: The Forgotten Story of the Most Daring Prison Break of the Pacific War by John D. Lukacs.

Re early reporting of atrocities:

Early atrocity reports - from Researching Japanese War Crimes: Introductory Essays (2006)

Assorted Statements

| Stimson to Secretary of State Cordell Hull,

February 5, 1942: "General MacArthur has reported... that American and British civilians in areas of the Philippines occupied by the Japanese are being subjected to extremely harsh treatment. The unnecessary harsh and rigid measures imposed, in sharp contrast to the moderate treatment of metropolitan Filipinos, are unquestionably designed to discredit the white race. I request that you strongly protest this unjustified treatment of civilians, and suggest that you present a threat of reprisals against the many Japanese nationals now enjoying negligible restrictions in the United States..." from Michi

Weglyn, Years of Infamy,

1976.